Administering Social Security: Challenges Yesterday and Today

Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 70, No. 3, 2010 (released August 2010)

In 2010, the Social Security Administration (SSA) celebrates the 75th anniversary of the passage of the Social Security Act. In those 75 years, SSA has been responsible for programs providing unemployment insurance, child welfare, and supervision of credit unions, among other duties. This article focuses on the administration of the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, although it also covers some of the other major programs SSA has been tasked with administering over the years—in particular, Medicare, Black Lung benefits, and Supplemental Security Income. The article depicts some of the challenges that have accompanied administering these programs and the steps that SSA has taken to meet those challenges. Whether implementing complex legislation in short timeframes or coping with natural disasters, SSA has found innovative ways to overcome problems and has evolved to meet society's changing needs.

The author is with the Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, Social Security Administration.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank the many people in SSA who helped her locate material and those who reviewed her paper and suggested improvements. Special thanks to Susan Grad for her help and patience and to Larry DeWitt, SSA's historian, for sharing his knowledge.

Contents of this publication are not copyrighted; any items may be reprinted, but citation of the Social Security Bulletin as the source is requested. The findings and conclusions presented in the Bulletin are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Social Security Administration.

Introduction

| ALJ | administrative law judge |

| AWR | annual wage reporting |

| BDI | Bureau of Disability Insurance |

| BDP | Bureau of Data Processing |

| BL | black lung |

| BOAI | Bureau of Old-Age Insurance |

| BOASI | Bureau of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance |

| CDR | Continuing Disability Review |

| CMS | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| DA&A | drug addiction and alcoholism |

| DAO | Division of Accounting Operations |

| DDO | Division of Disability Operations |

| DDS | Disability Determination Services |

| DI | Disability Insurance |

| DOC | data operating center |

| DOL | Department of Labor |

| EIN | employer identification number |

| FSA | Federal Security Agency |

| FY | fiscal year |

| GAO | General Accounting Office |

| HEW | Department of Health, Education, and Welfare |

| HI | Hospital Insurance |

| IBM | International Business Machines |

| IRS | Internal Revenue Service |

| LIS | low-income subsidy |

| MCS | Modernized Claims System |

| OASDI | Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance |

| OASI | Old-Age and Survivors Insurance |

| P.L. | Public Law |

| PSC | program service center |

| RRB | Railroad Retirement Board |

| SMI | Supplementary Medical Insurance |

| SSA | Social Security Administration |

| SSI | Supplementary Security Income |

| SSN | Social Security number |

They said it couldn't be done. In 1935, the Social Security Board, predecessor of the Social Security Administration (SSA), started to plan the implementation of the Social Security Act. Board administrators contacted European experts who were experienced with such programs. The experts replied that it was impossible to maintain a system for tracking individuals' earnings histories of the scope proposed for the United States (McKinley and Frase 1970, 20–21; SSA 1997a; SSA 1964a). Despite these pessimistic assessments, the Board persevered, and the Social Security program was successfully launched 75 years ago this month—and while the agency may have stumbled a few times during its 75-year history, it is still on its feet and getting the benefit payments out via the Treasury Department every month. In fact, SSA has never missed a month of sending the payments out on time.

SSA is an efficient agency with very low administrative costs of 0.9 percent of total expenditures (Board of Trustees 2009). Agency employees have a very well-defined sense of the agency's mission, and SSA constantly strives to improve its service to the public.

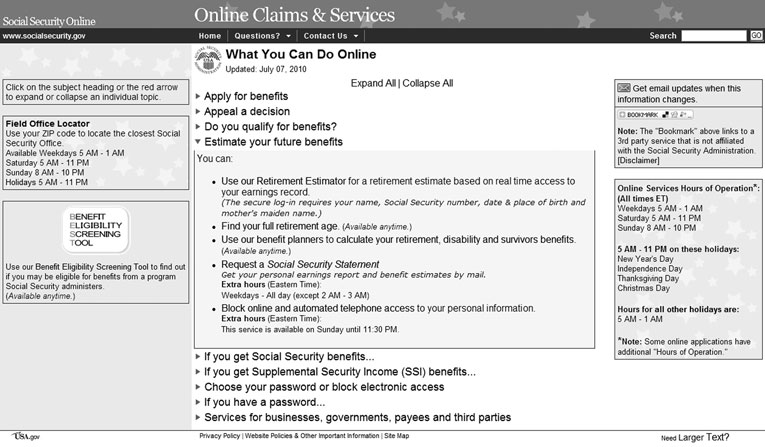

Today, SSA faces many challenges. Nearly 80 million baby boomers will file for retirement benefits over the next 20 years, an average of 10,000 per day (SSA 2008e). The agency was already struggling with a backlog of disability claim hearings when the 2008 recession hit. The recession compounded the agency's problems because the number of individuals filing for retirement and disability benefits increased.1 In addition, some states furloughed the SSA-funded state employees who make disability determinations for Social Security claimants. Keeping abreast of the latest technology on a restricted budget has also been a problem. The agency is exploring solutions, such as deploying Internet-based applications that enable claimants and third-party helpers to file applications for benefits and take certain postentitlement actions themselves, freeing SSA employees for other tasks.

Nevertheless, in reviewing the SSA Annual Reports to Congress over the past 75 years, one is struck by the frequency with which the section on administering the programs starts out with a sentence such as "SSA has had a very challenging year." Reviewing some of the major challenges that SSA has faced over the years, and how SSA has met them, seems appropriate as the agency prepares to meet its current challenges.

Over the past 75 years, SSA's responsibilities have involved programs as wide-ranging as unemployment insurance, child welfare, and credit union supervision, among others. This article deals largely with administering the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program. Over the years, SSA has been tasked with administering other major programs in addition to OASDI—in particular, Medicare, Black Lung benefits, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI). This article also covers the challenges of administering those programs.

The article is not comprehensive—space constraints do not permit an exhaustive account of the many challenges the agency has faced. Also, of necessity, descriptions of legislative provisions and program policy rules are somewhat generalized. This article is meant to give the reader some sense of the scope of the programs that SSA administers and of the challenges that arise in administering such programs.

1930s

President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act on August 14, 1935, establishing a three-person Social Security Board to administer a program of old-age retirement benefits based on a person's earnings history. The collection of payroll taxes was to begin on January 1, 1937, and the Board had to be prepared to keep records of the earnings on which those taxes were paid. So, the Board had less than 17 months to set up a recordkeeping system unparalleled in history. This would be a daunting task even if everything went smoothly, which of course it did not.

The first challenge the new agency faced was the absence of a budget. Senator Huey Long (D-LA) staged a filibuster on the closing day of the Senate session while the last deficiency appropriation bill, which included the Social Security item, was still pending. The session closed without an appropriation (Altmeyer 1966, 44). Given its deadline, the Social Security Board could not wait until the next legislative session to begin its work. The solution was to have the Federal Emergency Relief Administration,2 which had funded the President's Committee on Economic Security as a research project, set up another research project to develop ways and means of putting the Social Security Act into operation. Also, as the National Recovery Act had been declared unconstitutional in May 1935, the National Industrial Recovery Administration was liquidating and was "only too glad" to transfer office equipment and personnel to the Social Security Board (Altmeyer 1966, 44).

Building the Structure

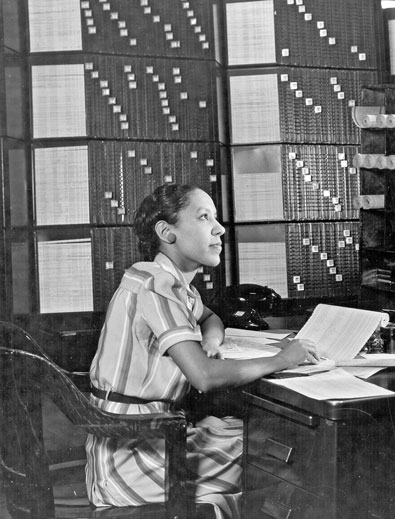

SSA History Museum & Archives.

The original structure of Social Security operations, created in December 1935, included three operating bureaus: Public Assistance, Unemployment Compensation, and Old-Age Benefits. The Bureau of Old-Age Benefits was responsible for Title II of the Social Security Act, providing for an old-age retirement benefit. Its functions included maintaining wage records, supervising field offices, examining and approving claims, and developing actuarial estimates. There were also five service bureaus: Accounts and Audits, Business Management, Research and Statistics, General Counsel, and Informational Service (Davis 1950, 53; SSA n.d. c).

Hiring workers to supplement the staff inherited from other agencies was another challenge. The Supreme Court declared the Agricultural Adjustment Act unconstitutional on January 7, 1936, calling into question whether Social Security would survive a legal challenge and discouraging job applications. Furthermore, a civil service register of eligible applicants was not yet available. The Board made extensive use of an exception to the requirement to hire from the register—an expert and attorney exemption clause—in order to make timely hires and circumvent salary restrictions. The Civil Service Commission limited to about 100 the number of field officers who could be hired under the expert clause, and friction soon developed when the Commission started questioning the Board's proposed classifications of workers. The Board also faced pressure from Congressmen to accept political appointments. Although a few compromises were made, the Board generally held fast against hiring those deemed unqualified (McKinley and Frase 1970).

Hiring for the Bureau of Old-Age Benefits was particularly hampered; as late as March 15, 1936, the Bureau had only five employees, including the director and his assistant. By June 30, 1936, the Board had hired 677 employees for its central office in Washington and only 71 for the field. It would be December 2, 1936, before the Civil Service Commission delivered a civil service register for the Bureau of Old-Age Benefits to use (McKinley and Frase 1970).

By December 2, 1935, the Board had established a Field Organization Committee to study problems and recommend ways to establish regional and field offices of the Bureau of Old-Age Benefits (Davis 1950, 117). The Field Organization Committee recommended locations for 12 regional offices, but the Board sometimes made "capricious and unfortunate changes" either to ward off or to satisfy pressure from senators, the White House, or Board members themselves (Davis 1950, 63; McKinley and Frase 1970, 96–102). The same was true for field office locations, with Congressmen appearing before the Board to plead the cause of specific cities (Zwintscher 1952, 70). In fact, when the Board temporarily decided to cancel one Senator's home town as a field office location and also resisted hiring an unqualified protégé of his, the incensed Senator attached an amendment to the Board's 1937 appropriations limiting the salary of those hired under the Board's expert clause and cutting by 5 percent the salary of the Board executive who told the Senator "no" (McKinley and Frase 1970, 88).

In its first report of January 29, 1936, the Field Organization Committee proposed at least one "district office" per state, located in state capitals, with additional district offices based on workload. The district offices were to have primary and secondary offices (later called branch offices) under them. District offices were to report to Washington, with the Bureau's regional representative to be responsible only for inspection and training functions. However, by July 1936, the regional representatives were given full supervisory authority over all the offices in their regions (Davis 1950, 125–126).

On April 6, 1937, the Board abandoned the concept of district and branch offices in favor of "field offices," all equally under the authority of the regional representative, but varying in size and staff according to "compensable load," presumably meaning the estimated number of covered workers (Davis 1950, 126). The Board established an eight-level field-office classification system. A class I field office's compensable load was 500,000, and the office manager's salary was $5,600; a class VIII office handled a compensable load of 26,000, and the manager's salary was $2,300 (Zwintscher 1952).

In deciding on the location and geographic boundaries of the field offices, a number of factors were considered, such as convenience to the public, uniform distribution of workloads, population patterns, trading zone3 boundaries, and administrative manageability (SSA 1965, 31). The Bureau opened its first district office on October 14, 1936, in Austin, Texas. When the newly appointed manager entered the musty space on the ground floor of an abandoned post office building, the equipment consisted of some dilapidated desks and chairs left behind when the post office moved out (SSA 1960b, 26). Finding equipment for the new field offices would prove to be a continuing problem.

Each field office established "itinerant stations" (today called contact stations) in remote communities whose residents could not travel to the field office without difficulty. The field office would arrange to use free space at another agency's facility to meet with the public. Often the space would amount to little more than a desk and a chair. A field employee would visit each station on a weekly, biweekly, or monthly schedule, depending on the workload. Post offices in these locations would display posters announcing the next visit of the field office representative. As workloads increased, the Board decided it was more efficient to station representatives permanently in some of these locations than to send a representative intermittently or to convert the stations to full-fledged field offices, so it opened some of them as 1- or 2-person branch offices (equivalent to today's resident stations), with minimal records, under the supervision of the territory's field office manager (Davis 1950, 126–127; Zwintscher 1952, 95–96).

In 1937, the Bureau of Old-Age Benefits was renamed the Bureau of Old-Age Insurance (BOAI). In turn, BOAI was renamed the Bureau of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (BOASI) when the president signed the Amendments to Title II of the Social Security Act on August 10, 1939. In 1940, the Bureau added a Control Division to handle the increased claims resulting from the 1939 amendments. Finally, BOASI established a Training Section in the Director's Office to take over the complete training program, a part of which had previously been handled by the Social Security Board (SSA n.d. c).

SSA History Museum & Archives.

Finding Office Space

Finding space for the growing agency was a major problem. The Board set up in temporary sites in Washington and split staff among multiple locations. Frequent moves and multiple locations became such a problem that Frank Bane, the Board's Executive Director, remarked that he would be quite willing to set up in a barn if he could have everyone under the same roof (McKinley and Frase 1970, 25).

It was impossible to find the kind of space in Washington that was going to be needed for the huge (and heavy) task of maintaining paper records on all Social Security number (SSN) holders and covered wage earners in the United States. Fortunately, the Board was able to find "suitable" space for its Accounting Operations close to the wharves in Baltimore—suitable more for the paper than for the employees, unfortunately. The space was in the Candler Building, a warehouse made for heavy industry that had formerly housed a Coca-Cola plant. The offices occupied by the Division of Accounting Operations (DAO) had wooden floors on top of cement, with sand in between. Employees often complained of the sand fleas (SSA 1997a). There was no air conditioning. The temperatures ranged from scorching hot in summer to freezing in winter (Simmons 1977, 12). As one Bureau employee later reported:

It was a huge factory, really. It was hot in the summer, we had the huge floor fans, which blew papers around. It didn't give us much comfort from those fans. And in the wintertime we used to sit at our cardpunch machines with our coats on and gloves because it was so cold. Then there was some company that made some kind of medication or something, the odor was horrible. They had big black bugs. I guess they came from the water. The girls used to be afraid of them, I would squash them. They made really a good sound. And another time I remember as we were sitting at our cardpunch machines, we were throwing paper clips at rats, and I mean they were rats. I remember one time the men were trying to get a rat down from the pipes that ran across the ceiling, and we watched them try to get that rat down. Then the mice, too, were doing damage, they were eating up all the data, the tabulations, etc. (SSA 1996d).

The employees worked at unfinished wooden tables whose rough lumber ran slivers into the workers' hands and arms (Altmeyer 1966, 72). Ringing bells told employees when to take their ten minute break in the morning and in the afternoon and when to go to lunch. Those wanting to smoke retired to the rest rooms to avoid sending the place up in flames (SSA 1996d). As this was during the Great Depression, people were glad to have a job even under these working conditions.

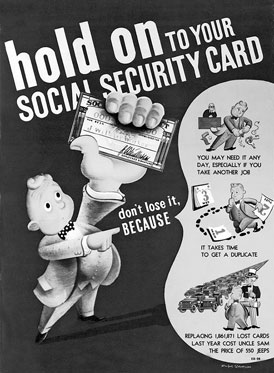

Issuing SSNs

The first step in accomplishing "the impossible" was to decide how to keep track of the earnings histories of every covered worker in the United States. A number of schemes were considered. One was a stamp system, as was used in some European countries. In this scheme, the employer would issue stamps to each employee based on the employee's earnings. The employee was to keep the stamps in a book and turn them in to the Social Security Board upon attaining age 65. In the end, however, the Board decided on the 9-digit SSN—so well known today—to identify each worker, in combination with an Employer Identification Number (EIN) to identify each employer (McKinley and Frase 1970).

The Board then had to figure out how to get an anticipated 22 million workers and 3.5 million employers registered by January 1, 1937, when the payroll tax would take effect. The plan was to set up a nationwide system of field offices to deal directly with the public, issuing numbers and taking claims; but as of September 30, 1936, the Bureau of Old-Age Benefits had only 164 employees. So, the Board turned to the Post Office Department for assistance (McKinley and Frase 1970, 309; Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 42).

The registration process was largely directed by the local postmasters. The first task was for mail carriers to make lists of employers on their routes. Their effort resulted in a list of 2.4 million employers (McKinley and Frase 1970). Beginning November 16, 1936, the post offices sent Form SS-4, Application for an EIN, to employers based on the lists they had compiled earlier that month. Along with information about the business establishment, the SS-4 asked for the number of workers employed. The mail carriers collected the completed SS-4s a week or two later. Based on the SS-4 information, the post offices delivered a supply of Forms SS-5, Application for an Account Number, to the employers the following week for distribution to employees (McKinley and Frase 1970, 368).

SSA History Museum & Archives.

Employees were permitted to return the completed SS-5 applications either to the employer, to any labor organization of which the employee was a member, to the letter carrier, or to the post office by hand or via mail (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 54). Of the 45,000 post offices then in existence, 1,017 first class offices were designated as "typing centers" to assign the SSNs, along with 57 "central accounting" post offices to assign SSNs for the second, third, and fourth class post offices within their area (McKinley and Frase 1970, 368). The Social Security Board supplied these centers with Office Record Form OA-702, in blocks of 1,000, with the account number preprinted. For each registrant, postal employees typed the information from the SS-5 onto the prenumbered OA-702 in duplicate. The employee's name was typed onto a detachable portion of the OA-702, which was then returned to the employee—this was the Social Security card. The post office mailed the completed Social Security cards to the employer, unless the employee had brought the SS-5 to the post office and waited in person for the typed card (Wyatt and Wandel 1937).

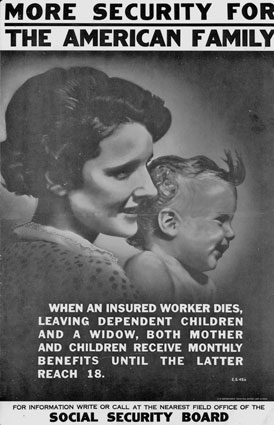

An active public information program was instituted to reach employers and employees through trade, labor, civil, veterans', and educational organizations (Pogge 1952, 5). The Board established an Informational Service in January 1936 to supervise public relations. The Board assumed that the American people would be unfamiliar with major concepts of social insurance, and the very complexity of the law necessitated a large-scale plan of popular education prior to registering employers and employees. This period coincided with the 1936 presidential campaign, and the Board was concerned about the potential for misconception and hostility toward the program (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 30–31).

At midyear, the Informational Service prepared the publicity campaign to encourage employers and workers to complete the application forms, but they did not plan to distribute the material until after the November 3 election. However, the Board accelerated the publicity release after a September speech in which the Republican presidential candidate, Alf Landon, criticized the program in a manner the Board considered seriously misleading. Also that year, many employers, in conjunction with the Landon campaign, began stuffing payroll envelopes with leaflets designed to undermine support for the nascent program. The Social Security Board was so alarmed that Chairman John G. Winant—a top Republican politician—resigned in order to campaign in defense of the Social Security Act. In addition, in October 1936 the Board released a film called "We the People and Social Security" along with a 4-page pamphlet entitled "Security in Your Old Age." It is estimated that some 4 million people saw the film, and nearly 8 million of the pamphlets were distributed by Election Day (McKinley and Frase 1970, 357–358).

On November 6, the campaign to encourage employers and employees to register began. A series of press releases outlined the procedure for assigning SSNs and carried sample Forms SS-4 and SS-5, as well as a Social Security card specimen. The campaign included three releases on old-age benefits in 24 languages distributed to the country's foreign language press. The Associated Press, the United Press, the Hearst newspaper chain, and many individual papers ran series of articles on old-age benefits and registration for weeks at a time. During the November and December initial registration period, there were also 12 nationwide radio broadcasts by well-known individuals and a host of local broadcasts arranged by the 56 skeletal field offices then in place. Over 3 million posters were distributed, 50 million more pamphlets were dispersed, and three additional newsreel trailers were shown to some 42 million people (McKinley and Frase 1970, 364–366). In addition, the Informational Service enlisted the help of thousands of kids from the National Youth Administration to "go out to the hedgerows and by ways, the gates of feebly stirring industrial plants, business offices, and billboards" to post some 3 million placards (Swift 1960, 11).

The publicity campaign and the Post Office Department's efforts produced over 22 million completed applications as of December 22, 1936, 28 days after the initial distribution of employee applications (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 62). During the first 4 months of the registration campaign, nearly 26 million SSNs and more than 2.6 million EINs were assigned (Corson 1938, 3). By June 1937, the Bureau had received about 30.3 million applications for SSNs (Pogge 1952, 5).

In November 1936 the Board assigned headquarters staff to 56 Bureau field offices, covering all but one of the cities where the Post Office Department had set up its "central accounting" offices. These 56 Bureau offices primarily answered questions and directed applicants to the post offices (McKinley and Frase 1970), but they were also busy working out procedures and methods with the Post Office Department and the Bureau of Internal Revenue. The field employees made extensive employer contacts—as many as 50 in a single day by some accounts. Phones rang all day with questions (SSA 1952b).

The Board twice had to ask the Post Office Department to extend its handling of the SSN applications, first through March 1937 and then through June 1937, before the Bureau could take over. During this time, Bureau employees often were stationed in the post offices to assist with typing the SSN applications (SSA 1952b). Effective July 1937, Bureau field offices—still numbering only 175 with 1,702 total employees—finally took over the enumeration workload from the post offices (Zwintscher 1952, 90; SSA 1965, 25). By that time, some 35 million SSNs had been issued at a cost of $5.7 million (SSA 1990, 1; McKinley and Frase 1970, 372). Still, the job was not finished. In July 1937 alone, Bureau field offices issued some 1.9 million additional SSNs (McKinley and Frase 1970, 368–373). Even with field office employees working evenings and Saturdays and with "managers and assistant managers, anyone who was available, pounding away at typewriters," the Bureau had to set up additional typing centers in its 12 regional offices to help with the workload (SSA 1965, 32; SSA 1952b).

Maintaining the SSNs

The post offices, and subsequently the Bureau's field offices, sent the completed SS-5 and the corresponding OA-702 forms in blocks of 500 to the Bureau's Records Office in Baltimore's Candler Building, where the SSN master files were to be kept. The local offices kept carbon copies of the OA-702 to use should an individual request a replacement card (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 58).

The Baltimore DAO officially opened on November 9, 1936, with 18 employees. It was vital to staff the office immediately. At the time, a hiring "apportionment" was in effect that required the Bureau to recruit a certain proportion of employees from each state. As a result, employees came from all parts of the country. It was thought that the central operation in the Candler building was temporary, and that the work would soon be dispersed to the 12 regions, so recruitment from distant states was logical (SSA 1952b). However, actual operations would reveal that decentralization was not really feasible.

The personnel office received 20 applications for every person hired. Because this was during the Great Depression, applicants for what were basically clerical jobs sometimes had amazing qualifications, including many PhDs and Phi Beta Kappas. On a single day—December 7, 1936—some 940 employees entered on duty. That morning the new arrivals lined down the stairways and out around the building. As each hire had to complete three or four copies of the personnel forms, it took until 5 a.m. to process them all. The personnel office was "a three-ring circus"—operating with one thin book of rules, regulations, and instructions, officers just learned as they went along (SSA 1952b; SSA 1960a, 32).

In November and December 1936, thousands of mail bags containing the completed forms OA-702 and SS-5 began arriving at the Candler Building to be coded and checked for accuracy. Here the Bureau installed a "great battery" of International Business Machines (IBM) equipment and deployed over 2,300 machine workers and checkers to handle the applications as quickly as they came in (McKinley and Frase 1970). The Baltimore Records Office used a nine-step process to create a permanent master record and to establish an earnings record for each individual. One hundred applications and office record cards, numbered consecutively, were sent through each operation together with a control unit of nine cards (one for each step). The appropriate control card was removed at the end of a step and sent to a control file to track the status of each block (McKinley and Frase 1970, 375).

When the Records Office received the Form SS-5 and the accompanying OA-702 from the local offices, different clerks working independently converted the two sets of information into numerical codes that could be transferred to punch cards. The first group of employees keyed information from the SS-5 into a master punch card for each individual. A tabulating machine used this master punch card to set up a numerical register of accounts stored in huge loose-leaf books. These volumes contained the SSN, name, and date of birth of each number holder. Each page contained 100 SSNs in numerical order. From these volumes, employees could learn the name and identifying information of an SSN's owner in a fraction of the time that would be required to locate the master punch card (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 120–121). The master punch card was also used in the earnings-posting operation to establish an earnings ledger for each individual.

SSA History Museum & Archives.

A second group of employees independently keyed the same information coded from the OA-702 to create an actuarial punch card (Fay and Wasserman 1938, 25). The actuarial punch card was created for actuarial and statistical purposes and was also used to set up the "visible index." Later known as the National Employee Index Flexoline File, or simply Flexoline, the visible index consisted of strips of thin bamboo covered with paper, 3/16 of an inch wide by 9 inches long—one for each SSN issued—set in a steel panel. The strips were inserted into the frame one by one, with some employees filing as many as 300 strips an hour. Each strip began with a 3-digit entry based on the Russell Soundex System (in which all surnames having the same basic consonants are grouped together), followed by the individual's surname, given name, middle initial, and SSN. The strips were mechanically prepared from the actuarial punch card and manually posted on the panel, sorted by the first letter of the surname and within each letter by phonetic code, then in each code group by the first seven letters of the first name, middle initial, year and month of birth, and SSN. Up to 1,600 panels were then hung on each rack (Staruch 1978, 29). Reportedly, experienced clerks were able to find any name and its corresponding account number in less than 60 seconds. In addition, the SS-5s were filmed on 16 millimeter, noninflammable film strips. In June 1938, officials bragged "This film is so compact that the entire file of 40 million photographed SS-5s is stored in 10 ordinary letter-size file cabinets" (Fay and Wasserman 1938, 25).

Keeping all these records was a huge storage problem. Before very long, it was necessary to stack the filing cabinets in two levels, with employees using rolling ladders to look into the upper bank (SSA 1997a). By September 28, 1951, the Flexoline contained over 129 million strips and was projected to increase at the rate of approximately 5 million per year. The index occupied approximately 36,000 square feet of floor space, one city block long on one side of the floor and one-third block long on each end of the floor (SSA 1952a).

Keeping Wage Records

The Bureau used a punch card technology that was relatively simple compared with today's computer capabilities, but in the 1930s much of the machinery SSA used was truly innovative. Keeping a record of each individual's lifetime earnings was an unprecedented task, and the technology to support this Herculean effort did not even exist—the Board had to work with private industry to create the needed technology (OTA 1986, 94).

Punch cards were a little longer and narrower than postcards, and about the same stiffness. The relative position of holes punched in a card represented numbers and letters. After punching, the cards were sent through a series of special machines that used electrical circuits to permit sorting in any desired order, producing duplicates, printing the information represented by the punched holes, tabulating or summarizing the information, and checking duplicate cards to ascertain that they matched the originals (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 119).

DAO prepared a punch card showing the employee's name, SSN, and the amount of earnings on the basis of each quarterly report. This card was checked against the corresponding master card to make certain that the name and SSN matched. If they matched, the card was run through an alphabetic accounting machine with the ledger sheet of the same individual. The machine read the amount represented by the punched holes and printed this amount on the ledger. Once a year, the quarterly earning cards for each employee were summarized to one card via a tabulator with a punch attachment, and the summary annual wage information was posted to the ledger account (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 123).

The Board had to decide whether its records should be centralized in a single location. An expert hired by the Board strongly recommended that the records be kept in the 12 regional offices, but Bureau executives questioned the wisdom of that approach. A compromise was reached: A pilot project kept all the records in Baltimore's Candler Building, but broke them into 12 sets based on the regional designations. It was soon evident that the regional approach would not work. Workers continuously migrated from one part of the country to another, and large employers paid their taxes and filed wage reports centrally for employees all over the country. Regionally maintained records would have required a continual workload transferring volumes of records between regions and maintaining special controls to keep track of the transfers. Therefore, early in 1939, a central mechanized section was set up to maintain all wage records. Subsequently, all the related files and records were combined and centralized (Altmeyer 1966, 86).

By 1938, DAO had about 500 employees using 222 card punch machines and 70 card sorters. Each day, DAO recorded about 715,000 accounts, with each card-punch operator keying in some 2,000 workers' wage reports (SSA 1992b, 15). By 1940, the Bureau had also implemented a system for posting employee accounts on a cyclical basis so that a continuous process used a relatively stable number of employees and equipment (Pogge 1952, 5–6). The Bureau's cost of maintaining a worker's account was only about 20 cents a year (Altmeyer 1966, 87).

An early crisis took form as the "John Doe" problem. Many employers reported earnings without providing a worker's name or SSN. The first report from the Bureau of Internal Revenue did not contain SSNs for about 12 percent of the wage items—and this rapidly increased in subsequent reports. The BOAI dubbed reports without SSNs "John Does" (Altmeyer 1966, 123). The Bureau quickly established procedures to contact employers for the identification information, and the "John Doe" rate decreased substantially, to 2.5 percent as early as 1939 (Pogge 1952, 5). A series of articles by Drew Pearson, a muckraking journalist of the period, repeatedly raised alarms about the John Doe problem and eroded some public confidence in the program (SSA 1967a; Altmeyer 1966, 123). However, by the time the Pearson articles were published, SSA figures showed that John Does were less than 1 percent of total wage reports, suggesting the articles reflected political differences rather than administrative inefficiency (OTA 1986, 95). Nevertheless, the Bureau would continue to receive incorrect names or SSNs on employer wage reports, and determining the correct identification information—and educating employers about the importance of supplying correct information—remained a large task into the 1950s (Pogge 1952, 5).

The Bureau also had to deal with "delinquent employers" who failed to report their worker's wages. Field offices would check the yellow pages in the telephone directory and the city directory against EIN files in an effort to find employers who were not reporting (SSA 1955a). The offices also got lists of employers to contact from state unemployment offices (SSA 1975b).

Processing Lump-Sum Claims

In addition to making certain every covered worker had an SSN and every employer had an EIN, the Social Security Board had to determine policy and procedures for processing claims. Monthly old-age benefits were not scheduled to begin until January 1942, but workers who turned age 65 before that date—or the survivors or estates of deceased workers—were able to claim a one-time payout in lieu of monthly benefits. The Board's General Counsel also interpreted Section 205 of the Social Security Act as requiring the Board to act as the administrator for the estates of persons whose death payments would amount to less than $500. In some states, this might entail finding and paying off any creditors before paying relatives (McKinley and Frase 1970, 310–311). One former SSA Dallas Regional Commissioner recalled how complex Louisiana inheritance laws were and how tedious it was to find 15 to 20 relatives entitled to a share of lump-sum payments, frequently as small as $1 (SSA 1985b, 16).

The earliest a lump-sum payment claim could be filed was January 1, 1937, but the Board did not have the forms ready until February 5, after the procedures had been reviewed by the Comptroller General (McKinley and Frase 1970). Once they received the approved procedures, field personnel were not happy with complicated and expensive requirements, such as notarizing certain information, and feared a negative public reaction (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 132).

At first, it was uncertain whether the claims clerks (today called claims representatives) could assist applicants. The General Accounting Office (GAO) took the position that a long-standing federal statute prohibited federal officials from assisting citizens in the prosecution of claims against the government. However, the Board argued that in this case the claimant had a statutory right to a specific benefit based on contributions into the old-age insurance system. Therefore, these were of a different character than usual claims against the government, which were payable out of general revenues. GAO relented, deciding that "it was not required to object." Once its role was settled, the Bureau impressed on its employees the importance of assisting claimants with their applications to make certain they received the benefits to which they were entitled and understood their rights and duties (Altmeyer 1966, 55). Some field office employees actively tracked down workers who had turned age 65 to notify them of their eligibility to claim benefits. Some even contacted funeral homes for information to help obtain claims for those who died after January 1, 1937 (SSA 1975b).

The manager of a local Bureau field office reviewed the claims forms and substantiating evidence (such as proof of age if the date of birth differed from that in Board records), affixed a transmittal form, and then forwarded the claims by way of the regional office to the Director of BOAI. The Director immediately transferred the forms to the Adjudication Operations Section of the Technical and Control Division. At the same time, the field office claims clerk sent a request to Baltimore's DAO to send earnings information to the Washington adjudication office (SSA 1974a). In the Washington office, a grade 5 employee in one of the four geographically based claims control units would associate the earnings information with the claim. If needed, additional information was requested from the field office. When he or she had everything needed, the employee would decide to allow or disallow the claim. The material would then go to a grade 7 reviewer who examined the claim and its substantiating evidence, determined the amount of the benefit, certified the approved claim for payment to the Treasury Department, and sent the claimant a notice (SSA 1974a).

Instructional material for processing claims was developed as work progressed. The original Social Security Act was less than six pages long, and the Board had to supplement the act with many rules and procedures for conducting its business. The first instruction on claims policy was Social Security Board Administrative Order No. 24. It included a page-and-a-half, single-spaced list of general principles for taking applications and ensuring confidentiality (McKinley and Frase 1970, 378).

The first claim was filed by a Cleveland motorman named Ernest Ackerman, who retired 1 day after the Social Security program began. During his 1 day of work under the program, his employer withheld a nickel in payroll taxes from Ackerman's pay. Ackerman received a lump-sum payment of 17 cents. During this period, the average payment was $58.06, and the smallest payment was 5 cents (SSA 1995a, 8).

In 1937 alone, the Bureau received between 70,000 and 80,000 claims for lump-sum benefits (Pogge 1952, 5; Altmeyer 1966, 86). At one point, the claims in Washington were "piled on top of file cabinets 3 feet deep." However, the Bureau soon dug itself out, and was able to assure the 1939 Advisory Council that it could handle the workload associated with moving the date when insured workers could begin receiving monthly benefits forward from 1942 to January 1, 1940 (SSA 1967a).

Training Employees

SSA's first Commissioner, Arthur Altmeyer, identified training as one of the keys to setting up a highly efficient administration in a very short time. Pervading all the training was an effort to instill in each employee his or her "affirmative responsibility for carrying out the provision of the Social Security Act" (Altmeyer 1966, 53).

The first training efforts were made as early as March 1936 when appointments to the field began. The Bureau of Research and Statistics, aided by the Field Organization Committee, improvised the initial training activities. The offices of the several Bureaus, and social insurance authorities outside the Board, conducted the training. The training generally had two components.

A 2-week basic training course emphasized the general economic background of the act. An analysis of the act's various provisions was provided for all employees above a certain grade (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 26–27). Field staff had to be experts not only on the old-age benefits program but also on other aspects of the act, as the public had difficulty differentiating between the various parts of the program. After classes, the students' evenings in the hotel room were filled with homework and study (SSA 1965, 32).

BOAI supplemented the basic course with a 3-week technical course for its own personnel. This course stressed the Bureau's operating procedures for tasks such as keeping wage records, adjudicating benefit claims, and assigning SSNs, as well as practical details of office management, personnel, and procurement regulations. BOAI provided special after-hours instruction for lower-grade employees and for those who had originally been unable to take the basic training course. By 1937, a full-time training staff was in place, and the Board integrated all of its training activities in a special training division within the Bureau of Business Management (Wyatt and Wandel 1937, 26–27).

Early Social Security Board employees later recalled their training experience with enthusiasm. They credit this early training with imbuing employees, from top executives to clericals, with a fierce loyalty to the Social Security program and a belief in the social philosophy it represented. They absorbed the lesson that they were working for the people who paid into the Social Security trust funds, and that these people deserved their courtesy, attention, and concern (SSA 1975a).

The Board put great stock in the importance of training and devoted considerable funds to the process, but this did not translate into money for the employees, who were expected to pay for their transportation to Washington and be reimbursed later. The Board paid neither a salary check nor a per diem for the training period (SSA 1975b).

1940s

Viewing Social Security strictly from a program perspective, one might conclude that not much happened during the 1940s. However, from an administrative standpoint, it was a very active decade, starting with implementing the 1939 Amendments to the Social Security Act. Also in 1939, the President's Reorganization Plan Number 1 established the Federal Security Agency (FSA). The Social Security Board became a part of FSA and was no longer an independent agency. The FSA encompassed the Social Security Board, the Public Health Service, the Office of Education, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and the U.S. Employment Service. The objective was to bring together agencies whose major purposes were to "promote social and economic security, educational opportunity, and the health of the citizens of the Nation" (FSA 1948, v).

The process of issuing SSNs and establishing earnings histories continued apace. By the end of January 1940, DAO had established almost 49.6 million worker accounts, plus more than 1.8 million Railroad Retirement Board (RRB) employee account numbers. By April 1940, the wage records kept in Baltimore had been converted from a regional to a national basis—a transition that required 28 months to complete. By July 1940, Bureau personnel totaled 8,744, with about half in DAO, about 3,000 in the field, and the rest in D.C. (SSA 1950).

SSA History Museum & Archives.

Implementing the 1939 Amendments

Signed into law on August 10, the 1939 amendments advanced the start date for monthly benefits from January 1942 to January 1940 and added benefits for dependents and survivors of retired beneficiaries. The Bureau, now renamed the Bureau of Old Age and Survivor's Insurance (BOASI), took immediate action, mailing letters to all individuals who had filed for the lump-sum payment at age 65 to alert them to their potential eligibility for monthly benefits. DAO sent transcripts of wage records for workers who attained age 65 from 1937 through 1940 to servicing field offices to enable staff to advise claimants of their possible benefits (Pogge 1952, 6). By April 1940, 63 more field offices were opened, including some 1-person branch offices (today known as resident stations), bringing the total number of field offices to 460. In addition, 1,296 itinerant stations (today known as contact stations) were established to assist the field offices (SSA 1965, 33).

The 1939 amendments markedly changed the nature of the field offices' functions. In addition to issuing SSNs and contacting employers about wage filings, they now served large numbers of people arriving to file claims for monthly benefits. To reflect the changing nature of the job, claims clerks were renamed claims assistants (SSA 1965, 32). Even so, the field offices still only completed the applications and gathered documentary evidence; before September 1941, they did not formally determine whether benefits were payable.

In the first year of administering monthly benefits, BOASI awarded benefits to about 250,000 individuals. On January 31, 1940, Ida M. Fuller became the first person to receive an old-age monthly benefit check, in the amount of $22.54. She had paid $24.75 in Social Security taxes between 1937 and 1939 on an income of $2,484 (SSA n.d. b). By the end of 1941, a total of 372,300 benefits totaling about $6.8 million in monthly payments were in force (Pogge 1952, 6–7). The numbers may not seem high, but they signify enormous effort in the era before electronic processing devices (Altmeyer 1966, 119). These claims brought with them many policy and procedural issues to resolve, such as when a widow has a child in her care, and whether tips and traveling expenses are "wages" under the act. BOASI also had to negotiate with the Bureau of Internal Revenue on definitions. For instance, there was a large "twilight" area in which it was difficult to determine whether a worker was an employee under the act. There were no precedents to follow, and complete information with which to resolve questions was lacking.

Eventually, as experience accumulated, BOASI developed its Claims Manual of operating instructions for making entitlement determinations and processing claims (Pogge 1952, 6). The first Claims Manual was a slim 35 pages. The Bureau had so much trouble getting the manual printed that a mimeographed version was sent out in advance (Davis 1950, 221). It was April 1940 before the printed version arrived (SSA 1950). The Claims Manual outlined standards and procedures for the development, review, and adjudication of claims. It was not updated very often, so it was supplemented with "adjudication instructions," copies of which were kept by each claims adjudicator.

A policy group in the Claims Division had written the Claims Manual, but legal interpretations were largely made on the fly as cases came up. The claims adjudicators in Washington referred any case with questions about legal interpretations to the unit chief, who would take the case to the head of the Claims Division. The question would then be submitted to the General Counsel for legal opinion. Before long, claims adjudicators all had piles of different kinds of cases on their desks awaiting legal decisions (SSA 1974a).

Administering monthly benefit payments brought the problem of how best to maintain payment records. At the time, the normal accounting practice was to keep a ledger account for each individual. BOASI considered this approach, and even ordered millions of ledgers and posted payments to them for a few months, but it soon was obvious that an unacceptable number of clerks would be required to maintain the individual accounts as the benefit rolls grew. Instead, BOASI determined to use a claims folder system, with a folder set up for each account. All actions affecting payments were filed systematically in the claims folder. BOASI employees could reconstruct the payment history of any beneficiary in a matter of minutes using the claims folder (Pogge 1952, 7).

The Claims Correspondence and Control Section (later known as the Control Division) was responsible for keeping the records. The Section started off with 50 people and was budgeted to increase to 140 with the next fiscal year (FY), but it soon became apparent that over 500 employees would be needed (SSA 1952b).

BOASI also had to devise a way to make available at all times information on which persons were entitled to benefits and which were due a payment each month. The wage records operation also had to find a way to identify any beneficiaries who earned more than $14.99 per month, making them ineligible for a payment for that month. BOASI developed a punch card system for controlling the payment status of each beneficiary for each month. This system enabled the Bureau to prepare a monthly statement showing the activity of the beneficiary rolls and to balance this statement against external controls established by the Treasury disbursing office within a few days of the end of the month (Pogge 1952, 6–7; SSA 1952b).

Supporting the War Effort

No sooner was the Social Security Board's organization in place and its employees trained than another challenge arose. World War II became the nation's priority, and large numbers of BOASI employees left to join the war effort. Because agencies dealing directly with the war were given priority on hiring, finding replacements for the departing BOASI workers was problematic. The surplus of laborers during the Depression now became a shortage.

Despite its manpower challenges, BOASI supported the war effort in a number of ways. The U.S. government commissioned economic surveys to provide a base for integrating all the nation's industries into the war effort. With its widespread network of offices and its 3,900 experienced field staff, BOASI took responsibility for conducting the economic surveys. Field assistants (later renamed field representatives) had vast experience visiting employers to resolve wage-reporting problems and determine employer-employee relationships. These BOASI employees were ideal for collecting information on workers' job duties, the materials they used, the supplies they needed, and whether they had more of certain critical materials (such as steel) than they needed. The surveys went on through the spring, summer, and fall of 1942, and the information was submitted to the War Production Board (Olcott 1981, 14–15; SSA 1975b). The Bureau also provided war agencies with statistical data derived from its wage record operations (Pogge 1952, 8).

Also starting in 1942, BOASI took on a "Civilian War Benefits" program that paid benefits to families of civilian war casualties such as American construction workers in the Pacific islands. Monthly benefits for wives (and a few widows and parents) ranged between $30 and $45 depending on the worker's former wages, with children receiving less. The first payments went out in March 1942, and by December 1942 BOASI was paying $38,800 a month to 1,467 beneficiaries. This program gave BOASI its first experience handling disability-based benefits. Starting in November 1942, payment went to civilians injured while engaged in civil defense work, such as Civil Air Patrol or the Aircraft Warning Service, or during enemy actions such as the Pearl Harbor attack (Olcott 1981, 14–15). The program also paid benefits to Philippine Island civilians disabled as a result of enemy action (Pogge 1952, 8). Monthly cash benefits ranging from $10 to $85 were paid for temporary total disability or permanent disability of at least 30 percent (Altmeyer 1966, 140; DeWitt 1997). BOASI worked with physicians on loan from the Public Health Service to develop procedures and policies (SSA 1996c).

SSA History Museum & Archives.

The demand for defense-related office space in the Washington, D.C., area peaked just as a new building intended to house and centralize Social Security's headquarters was completed. BOASI had to go elsewhere. Headquarters staff moved from D.C. to Baltimore on June 1, 1942. The Claims Division and the Control Division, which respectively authorized claims payments and maintained the beneficiary records, were simultaneously merged into a Claims Control Division and decentralized from the D.C. area, moving into "area offices" in Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and New Orleans (Olcott 1981, 15–16). In 1946, the New Orleans area office was moved to Birmingham, and a sixth area office was opened in Kansas City (SSA 1952b; Davis 1950, 127). The Bureau also set up a DAO branch in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania (Pogge 1952, 8; SSA 1952b).

On September 15, 1941, responsibility for reconciliation of wages, development of claims, and computation of benefit amounts was shifted from the Washington Claims Division to the field offices. However, claims still received a 100-percent review and payment authorization in the Claims Division (SSA n.d. b).

BOASI also looked for ways to eliminate unnecessary work to alleviate the staffing shortage. BOASI used a special technique known as the "Why survey," in which all Bureau employees participated over several months. In this survey, the Bureau used teams of employees to analyze each operating step that had to be performed and asked "Why do we do this? Why do we do it this way? Why can't it be eliminated? Why can't it be improved? Why can't it be combined with other operations? What does this step add to the final product?" The Bureau received about 6,600 suggestions from about 2,400 employees, and adopted about a quarter of the suggestions. This effort enabled the Bureau to cope with a staff reduction from about 9,850 to 8,300 even though the workload did not decline (Pogge 1952, 8; Futterman 1960, 20).

Restructuring in the Post-War Period

On July 16, 1946, the Social Security Board was abolished. In its place, the FSA created the Social Security Administration (SSA), with all of the duties, powers, and functions of the old Board. The old Executive Director's Office became the Office of the Commissioner of Social Security. Arthur Altmeyer, who had been the Board's chairman, became SSA's first Commissioner.

There were now four "operating" bureaus (actually program bureaus): The Bureau of Public Assistance, the Bureau of Employment Security, a new Children's Bureau, and BOASI. In 1947, BOASI supervised the 12 regional representatives and their staffs, 464 field offices, 6 branch offices, 2,052 itinerant stations, and 13 detached field stations (Davis 1950; FSA 1948).

Major changes occurred in DAO. The old individual ledger sheets that held individuals' earnings histories were replaced by yearly listings prepared by an electrical accounting machine using the annual summary and detail earnings punch cards. In addition, DAO began microfilming records, which not only introduced workyear savings, but also freed up filing equipment and space. Also at this time, responsibility for assigning employer account numbers was transferred to the Bureau of Internal Revenue (Pogge 1952, 9).

1950s

The 1950s were a period of growth for SSA, in coverage of additional workers, in new beneficiary entitlements, and in agency employment. While taking on new workloads, SSA also had to deal with inadequate and substandard facilities.

The decade brought many structural changes for SSA. By 1952, there were over 500 field offices (SSA 1952b). On July 19, 1954, the field offices were redesignated "district offices," although the agency has since continued to refer to both district and branch offices generically as field offices. Area offices were renamed "payment centers" on July 8, 1958. In September 1958, a new payment center was established in Baltimore to handle cash disability payments and the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) payments for beneficiaries living in foreign countries (SSA n.d. b).

Meanwhile, SSA became a part of a new agency. On April 11, 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower abolished the FSA and in its place created the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW).

Implementing the 1950 Amendments

The 1950 Social Security Act Amendments extended coverage under the OASI program to about 10 million more persons effective 1951, including the nonfarm self-employed other than doctors, lawyers, engineers, and members of certain other professional groups; regularly employed domestic and farm workers; a small number of federal employees who were not covered under the civil service retirement program; members of a few very small occupational groups; and workers in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. In addition, voluntary coverage was offered to the 1.5 million people who worked for state and local governments but were not under retirement systems and to about 600,000 employees of nonprofit organizations (Cohen and Myers 1950). The 1950 amendments also liberalized the eligibility requirements, making about 700,000 persons immediately eligible for benefits; increased benefits substantially for about 3 million existing beneficiaries, effective September 1, 1950; raised the wage base for tax and benefit computation purposes; and provided a new contribution schedule (SSA n.d. b; Pogge 1952, 9). Without question, these were major changes.

SSA History Museum & Archives.

Unlike its experience with the 1939 amendments, BOASI had a seasoned and well-trained staff to implement the 1950 legislation. BOASI also began preparing for the legislation early and thoroughly. So, although this legislation contained the most extensive changes in the program's 15-year history, BOASI was equal to the task (SSA 1952b).

The Bureau used veteran employees to quickly train new employees, adapted work flows and procedures, and launched an extensive information program to reach potential beneficiaries. As workloads peaked, the Bureau shifted regular employees from one operation to another and used overtime rather than hiring temporary employees (Pogge 1952, 9).

The new coverage provisions meant that millions of new employers and employees had to be registered and wage record accounts established. Forms and procedures for nonprofit organizations had to be developed by January 1, 1951, and interpretations of the law had to be settled to provide states with guidance in framing legislation and negotiating coverage agreements. Forms for reporting self-employment did not have to be finalized until January 1, 1952, but Bureau staff had to work closely with the Bureau of Internal Revenue before then to develop regulations and uniform coverage determinations. An informational booklet with a tear-off coupon for registering household employees was widely distributed, as well as an envelope-style tax return form for reporting household wages. BOASI worked with the Department of Agriculture to distribute information to farm residents (Pogge 1952, 10).

New coverage provisions added new complexity to the program, and additional complexity resulted from legislative provisions to ensure that no one was disadvantaged by changes in program rules. Consequently, already in the 1950s, as many as 16 or 17 different recomputations might be needed. In response, SSA Commissioner Robert Ball initiated a "program simplification" project in the Program Analysis Division. The idea was to have a workgroup examine specific program areas and try to simplify the provisions. The workgroup recommendations to simplify the computations would finally be enacted in the 1960 amendments. This project would be just the first of many SSA attempts to find ways of simplifying Social Security programs (SSA 1996e).

In FY 1951, BOASI awarded benefits to 1.4 million persons, more than twice the previous record. The volume of work had tripled since 1941, and soaring postwar inflation tremendously increased operating costs. Nevertheless, efficiencies the Bureau had implemented enabled it to successfully handle the new workload—although claims processing time increased substantially. The recent introduction of electronic accounting machines supported the mechanical calculation of benefit amounts from punch cards containing wage-record information. By 1951, 47 employees were handling the amount of work that had required 100 persons just 10 years earlier (Pogge 1952, 10).

Because a provision in the 1950 amendments brought about a more liberal benefit computation effective July 1, 1952, many claimants waited until then to file for benefits. As a result, the new claims workload increased by 39 percent. Additional amendments on July 18, 1952, increased benefits for the 4.6 million beneficiaries already on the rolls, and these increases had to be reflected in the September benefit checks. In spite of these additional workloads, the incoming Eisenhower Administration sharply curtailed the Bureau's budgets for the first half of 1953, preventing the Bureau from adding staff to handle the resulting backlogs (OTA 1986, 96).

Implementing the 1954 Amendments

On September 1, 1954, the Social Security Act was amended to extend OASI coverage to self-employed farmers and workers in specified other professions, additional farm and domestic employees, members of state and local government retirement systems on a voluntary group basis, and individual ministers and members of religious orders through election. Additionally, a disability freeze provision4 was enacted to protect the benefit rights of disabled persons (SSA n.d. b).

Area offices worked extensive overtime to compute the benefit increases that resulted from the 1954 amendments. SSA employees had to file an accounting machine-produced form indicating the new benefit amount in each beneficiary's folder. DAO sent employees to each of the six area offices to help. The Philadelphia Area Office, with about 440 employees, worked 2,000 hours of overtime—equivalent to 250 work days—between January 3 and January 11, 1955, alone (SSA 1955b).

To determine farm coverage, SSA had to formulate a policy for measuring "material participation."5 For assistance, SSA turned to the Agricultural Extension Service of the Department of Agriculture and the University of Maryland. SSA policy developers met with county agents and visited farms in the area to speak with actual farm operators about how the program could work. Because Maryland did not represent some farm situations satisfactorily, SSA then expanded its research into Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Louisiana. Its findings enabled SSA to develop a workable policy (Lowrey 1955, 5). However, covering farmers caused spikes in claims. Once again, the agency temporarily shifted employees to offices where the workloads were the heaviest (SSA 1960a, 34).

In September 1954, the Bureau established the Division of Disability Operations (DDO) to implement the disability freeze. Under a federal-state partnership that exists even today, each state designated an agency to make a determination on disability for applications filed in the local BOASI field offices. The idea behind this state-federal arrangement was to tie the receipt of cash disability benefits more closely to rehabilitation services, which were state functions. Also, Congress did not trust SSA to be strict enough with the medical determinations. SSA paid the state's administrative costs for making the determinations (SSA 1996c). DDO was responsible for negotiations with the state agencies, reviewing state agency decisions on disability, making original decisions for those cases not yet covered by state agreements, establishing standards and procedures for paying the state agencies, and developing medical guides, polices, and training materials for use by both BOASI and state agency personnel. Frequent amendments liberalizing the program posed additional administrative challenges (Christgau 1955, 16).

District offices were also affected, as they had to interview the applicants, complete a medical history, record their observations, and obtain the medical records. In response to the disability freeze, SSA opened a number of new offices, many of them in medium-sized towns and rural areas (SSA 1960a, 34). DDO provided training for the district offices to ensure they were prepared. In January 1955, the Bureau began taking disability freeze applications. There were no special forms for capturing the medical information; employees filled out a long narrative, usually six to nine pages (SSA 1995c). The Bureau had to deal with claims not only from the recently disabled but also from those disabled for many years. The Bureau took half a million claims in just the first few months. The workload in the first quarter of 1955 was equal to the workload for a full year in 1946 (SSA 1955c).

To develop its disability determination policy, DDO staff consulted with the Veterans Administration and the RRB, agencies that already had disability programs (SSA 1996c). Gaining the cooperation and support of the medical community was a major challenge. DDO set up a Medical Advisory Committee, which included prominent private-sector medical doctors suggested by the American Medical Association (AMA), to provide advice and recommendations for disability policy and guidelines. When SSA had the Committee's support, it could usually count on support from the AMA (SSA 1979, 23).

Taking on the Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) Program

On August 1, 1956, the Social Security Act was amended to provide monthly benefits to permanently and totally disabled workers aged 50–64; to pay child's benefits to disabled children aged 18 or older of retired or deceased workers, if their disability began before age 18; and to lower the retirement age to 62 for widows and female parents. In November 1956, retirement benefits also became payable to women at age 62 (SSA n.d. b).

The passage of DI benefits was extremely controversial, with many special interest groups vociferously opposed. Congress and the Eisenhower Administration expressed concerns about potential program costs and encouraged SSA to take a "strict" approach to administering the new benefits. However, constituent complaints about the high disallowance rate prompted Congress to hold high-profile hearings on the disability program in 1958. As a result, some administrative procedures and policies were made less restrictive. In addition, following these hearings, SSA published its disability medical listings6 for the first time (SSA 2001b).

SSA History Museum & Archives.

Use of state agencies to make the disability determination was continued in the 1956 legislation. However, although the state agencies decided whether a person's impairment met the requirements for disability benefit entitlement, DDO reviewed every decision (SSA 1995e).

With increased workloads in the district offices came heavy claims loads in the payment centers. The number of beneficiaries grew from 9.1 million in 1956 to almost 12.5 million in 1958. Although Bureau employment grew from 18,000 in 1956 to 22,500 in 1958, ingenuity and new, more efficient processes were required to cope with the additional work (SSA 1960a, 34).

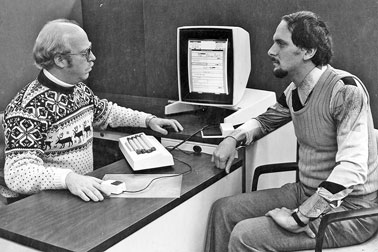

Trying New Technology

In the 1950s, the United States entered the computer age, and SSA once more was a leader in adopting new technology. In 1950, the Bureau installed its first "high-speed electronic calculator" for claims processing (FSA 1950, 32). In July 1955, the Bureau acquired an IBM 705 II Data Processing System for posting earnings, computing benefits, and reinstating incorrectly reported earnings items (SSA 1960c; SSA 1964b; SSA n.d. b). On July 1, 1956, the earnings posting operation changed from an 80-column IBM punched card and the IBM 407 Accounting Machine to electronic data processing equipment which stored information on magnetic tape using a binary code. One reel of magnetic tape could hold the information from almost 32,400 punched cards, and the Summary Card File alone had 120 million records to be converted to tape (SSA 1960c, 20–21).

SSA also helped pioneer a microfilm printer that linked computer and microfilm technology (OTA 1986, 99). Until 1958, the Bureau was still using the Flexoline to keep track of SSNs issued. The mammoth file took up a city block of floor space. It was growing at the rate of about 3 million names a year and required 6,000 additional square feet of space every 12 months. SSA plainly could not continue using the Flexoline file indefinitely. In 1958, the existing National Employee Index was microfilmed. By 1964, the 200 million names in the National Employee Index were contained on 2,005 reels of magnetic tape divided among about 90 "stations," each equipped with high-speed microfilm readers (SSA 1964b).

1960s

After responding to the challenges posed by extensive growth in the Social Security program in the 1950s, SSA was poised for additional challenges in the 1960s. The biggest of these was tackling an entirely new program—Medicare.

SSA also underwent a major organizational change. On January 28, 1963, SSA shed many of its former responsibilities when HEW moved the Children's Bureau and the Bureau of Public Assistance into a new Welfare Administration. SSA's role would now be essentially identical with that of the now-abolished BOASI, focusing primarily on the retirement, survivors, and disability insurance programs.

In March 1965, further organizational changes at SSA created four program bureaus: The Bureau of Retirement and Survivors Insurance, the Bureau of Disability Insurance (BDI), the Bureau of Health Insurance, and the Bureau of Federal Credit Unions. SSA also created a Bureau of Data Processing and Accounting—later shortened to the Bureau of Data Processing (BDP)—that assumed responsibility for the operational functions of the former DAO (SSA n.d. b).

Maintaining Public Service

In 1961, the agency's workforce provided 25,829 "man-years" of service, of which 11,473 were dedicated to processing claims and about 5,000 were spent posting wages. BOASI had 11 regional offices, 584 district offices, and 3,541 contact stations (previously called itinerant stations). Field offices still took claims, developed the evidence, and sent the applications into the seven payment centers for final adjudication and certification of payment to the Treasury Department. More than 35 days typically elapsed between taking an application for benefits and payment certification. Of this time, 6 hours was for BOASI employees' direct work and the rest was spent physically moving materials from one work station to another or awaiting evidentiary documents (Ladd and others 1961; Futterman 1960, 2).

SSA was considered a well-run organization. A report of the 1965 Advisory Council on Social Security stated:

From our own observations and from the evaluation of others, we believe that the huge task of administering the social security program, a task which involves the rights of many millions of people and the payment of billions of dollars a year, is being handled effectively and efficiently.

Administrative costs have been kept down to only 2.2 percent of benefit payments, partly as a consequence of the use of the latest in methods and machinery. This low administrative cost, however, has not been achieved by sacrificing high-quality service to the public. Employees at all levels have combined efficient performance of duties with responsiveness to the public and a friendly and sympathetic concern for the aged, the disabled, and the widows and orphans who are the program's beneficiaries.

We would like to register our belief that accomplishment of the purpose of the social security program requires that this high quality of administration—nonpartisan and professional—be continued (Advisory Council 1965, 39–40).

SSA employees' dedication to serving the public would be a factor in successfully handling its next big challenge: implementing the 1965 amendments. As an initial step, the Commissioner in 1965 approved the establishment of branch offices under the direction of the District Office Managers (SSA n.d. b).

Launching Medicare

The 1965 Amendments to the Social Security Act, enacted July 30, provided hospital insurance (HI) to persons aged 65 or older who were entitled to monthly Social Security retirement benefits, as well as to unentitled individuals who would reach age 65 before 1968 (Medicare Part A). All persons aged 65 or older were also permitted to voluntarily purchase Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI) for physician's services (Medicare Part B). Medicare was to go into effect July 1, 1966, giving the agency less than a year to implement the program.

Simultaneously, the agency had to implement changes to the OASDI program. The new law extended eligibility to students, divorced wives, and widows aged 60 and liberalized the retirement test and the definition of disability. It also instituted a "transitional insured status" for persons who reached age 72 before 1969. In addition, it provided a 7-percent increase in benefits retroactive to January 1, 1965.

Coverage in the voluntary SMI program was to begin July 1, 1966. The enrollment deadline for those aged 65 or older was March 31, 1966. Late enrollment would result in delayed coverage and a premium penalty. Persons attaining age 65 after March 31, 1966, had to enroll during the 3-month period preceding their 65th birthday. The SMI premium of $3 a month was to be deducted from the Social Security benefit check.

The effort required to create the Medicare program while simultaneously implementing the OASDI benefit portion of the 1965 legislation was staggering. First, 19 million potential Medicare beneficiaries had to be identified and contacted to determine their eligibility. SSA staff had to elicit and process SMI enrollment forms. The agency also had to prepare and certify those who would be providing hospital and medical services covered under HI and SMI. SSA had to develop contracts with the intermediaries that would handle reimbursement for hospital services rendered and also with the carriers that would determine "reasonable charges" and handle the reimbursement for SMI services. SSA needed an administrative infrastructure for Medicare, which required hiring and training 9,000 employees, setting up 100 new field offices, coordinating activities with numerous other federal agencies, and developing internal systems capacity. In addition, SSA had to develop Medicare program policy through consultation with other agencies and many interest groups (Ball 1965; Gluck and Reno 2001, iv–v).

Commissioner Robert Ball later attributed the Agency's success in implementing Medicare to three factors: an existing nationwide organization that was disciplined and experienced in dealing with the public, had high morale, and was eager to do the job; a group of central planners and leaders with enthusiasm, imagination, and quality leadership skills; and an almost complete delegation of authority and responsibility to SSA from higher levels (Gluck and Reno 2001, 9–10).

Shortly after the legislation was signed, SSA mailed a punch-card application form together with an information pamphlet to all Social Security, civil service annuity, and railroad retirement beneficiaries who were within 3 months of their 65th birthday or older. SSA also obtained leads from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS, successor to the Bureau of Internal Revenue), welfare rolls, state and local retirement plan agencies, nursing homes—any source that could provide a list of names and addresses for the elderly. Two follow-up mailings went out to nonrespondents. SSA also hired advocacy groups for seniors to go door-to-door. Even the Forest Service was enlisted to look for people camping out in the woods (SSA 2001b; SSA 1995b).

SSA distributed over 120 million booklets about Medicare and sent a continuous flow of materials to the media, which provided unstinting support throughout the initial enrollment period. Newspapers printed column after column on the new program; radio and television stations presented live and recorded programs explaining the law; and post offices widely displayed posters. The number of news items ran into many hundreds of thousands. District office employees made nearly 90,000 talks, 194,000 radio broadcasts, and 5,000 live television appearances; they also manned 29,500 exhibits (HEW 1966, 21).