Oral Histories

Isadore Herbert "Herb" Borgen

| Soundclip from Borgen interview. (Concerning the war-time Civilian War Benefits program--a little-known precursor to Social Security disability. [In RealAudio format] |

Photo Gallery

Herb Borgen, seated center, circa 1938, with a Claims Policy Unit, in Washington, D.C.SSA History Archives.

Herb Borgen (standing right), with the some of the Region II Review Staff, BOASI, circa 1941. SSA History Archives.

Herb Borgen with the Central Disability Planning Staff in the summer of 1952. The staff was located in room 826 of the Equitable Building in downtown Baltimore. Also shown, left to right): Lois Garvin; Lorraine Hejl; Ed Mueller; Art Hess; Gus Meyers; Herb Borgen; Shirley Winner; Jim Calhoon; Dr. Carl Rice. SSA History Archives.

Herb Borgen is seen fifth from left in the middle row at this State Agencies Conference in Newport, Rhode Island, December, 1957. SSA History Archives.

Herb Borgen, fourth from left, front row, at BOASI Conference in Salt Lake City, Utah, September 1959. SSA History Archives.

Herb Borgen with Mendel Kaufman, 3/27/61. SSA History Archives.

Herb Borgen with, left to right: Roy Carmel; Neal Purnis and Isidore Brauner. SSA History Archives.

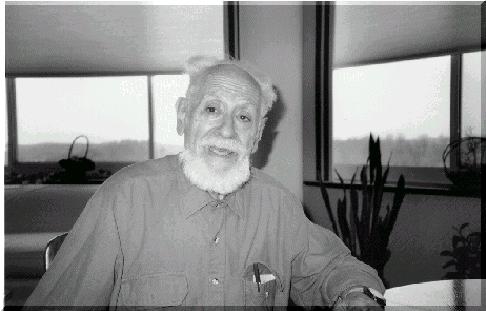

Herb Borgen Oral History Interview

This is an interview in the SSA Oral History Series. The interviewee is Herb Borgen. The interviewer is Larry DeWitt, SSA Historian. The interviews took place on 4/3/96; 5/15/96; and 5/29/96, at Mr. Borgen's home in Baltimore, Maryland. The interviewer's questions and any editorial comments appear in italics. Mr. Borgen was given an opportunity to review and edit the raw transcript.

Q: Herb, what I'd like you to start with is just by telling us how it is you came to work for SSA. What was your first job and what were the circumstances of you coming here for the first time?

Borgen: That's a long story in itself.

Q: That's alright. I've got lots of tape.

Borgen: I was in law school--Columbia. I was sick; I lost a year. I got out in 1934, which was not a very good year, especially for rather poor guys who managed to get through school.

The Department of Justice had an arm known as the FBI, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which was the only bureau which separated itself from the Department of which it was a constituent. They were the Federal Bureau of Investigation. J. Edgar Hoover was the guy who ran his little empire, and he advertised--I don't remember where-- "Lawyers and law school graduates to apply for a civil service exam. Fingerprint Classifier." I took it; I got the job. It was down in Washington. That was in 1934.

Right out of school I went down and I didn't take the bar exam or anything, just packed up and went. That meant three meals a day and a roof, and so forth, and more or less, independence. Salary was $1,440 a year, payable every 2 weeks. Washington was a very different city in those days. Roosevelt was in...do you want me to go through this stuff?

Q: Yes, please. Absolutely.

Borgen: It was a southern city. Congress had been a southern stronghold and the southern Representatives and Senators, and the municipal government, and everything, was southern.

Well, I found myself a room. All the houses down along Pennsylvania Avenue, E Street, F Street, D Street and about 20th and 21st Street NW--there were small homes. A lot of civil servants from way back lived with their families and they had extra rooms that they rented out. With Roosevelt a whole flock of new people were coming in. The city was teaming with young people and it was a great new world.

Of course Fingerprint Classifier wasn't going to be contributing very much to that, but the atmosphere was charged. Working with me were a whole flock of people--lawyers, brokers, Ph.Ds who had been in the field of education--all sorts of people from all over the country. In those days civil service was apportioned among the states depending on representation, and in each state a certain quota, you might say, were selected from the exams. It might still be working--I don't know. So there were people from all over the country and in the place where I lived, Lou Zawatzky and a number of other guys I can't think of, we had rooms. We lived there and we ate out. My budget was $1 a day for food, and that was ample. It was amazing. Dinner across the street from the old State, War and Navy building, which is now one of the executive offices right next to White House on 17th Street, there was this restaurant (the name escapes me)--dinner, white table cloth, full course, desert, tip and all--60 cents! So we survived. It was ok.

The working conditions at Fingerprint Classifying were--everybody was overeducated, over-experienced, under-classified...

Q: It sounds like a clerical job in some ways.

Borgen: Fingerprint Classifier? You may have seen those fingerprint cards at the post offices or something. Well, every civil service applicant filed one, and all the police departments in all the states sent in their files. A variety of reasons for filing.

First of all you, have to classify the print. You have to find some system for identifying groups, and then reducing them to a small group, and then you check it with your glass and make the necessary identification. What in the hell you needed a law student for, I don't know.

Q: Right. Ok.

Borgen: But that was the claim. You had to make an identification which could stand up in court. Actually anybody with eyes could do it.

It was a very interesting place. I ran into trouble there. I had been suffering from constipation all my life so I used to have to spend a lot of time in the men's room, comparatively, and when I was in the men's room I did my business, but in the men's room is where all the guys got together to discuss football scores and how they were going to bet and so forth, and who was your bookie. And there were public telephones and they would go to the public telephones and place their bets. That was rampant. That was not my type because I don't follow any of these sports and I'm not a gambler. I was in the bathroom and they would watch (Hoover had his men out) the amount of time you spent in the washrooms. There was a staff meeting and we got bawled out. I raised my hand. "I go to the bathroom because it's the call of nature--I have to go. I have nothing to do with this other stuff." "Borgen, the more you talk, the worse it will be."

When celebrities would come, Hollywood people and so forth, everybody had to dress up specially and Hoover would parade the people around.

Occasionally I'd be sick (rarely); I'd be in my little room there in summer, sweltering...

Q: No air conditioning.

Borgen: Come on. No fan even. You just opened the window. I called in sick and at one point there's a knock on the door--a nurse from the Department of Justice. I said, "Oh good. Somebody who can help me a little. I was feeling lousy." "We were just checking to make sure you were really sick." OK, that's a great help. And another time I had little blisters on my hand. I went to see the nurse. She said, "Oh, that could be very contagious. Go out. Don't touch anything. Go to the doctor." I went to the doctor. He says, "Do you want to take a vacation?" I said, "Well I could go to New York for a couple of days." He says, "Go out and come back to work in a couple of days." I did. At that time the doctor (most of the guys used him)--he was the physician for the Washington baseball team, a fat jovial guy.

And at one time the Attorney General, Homer Cummings, met with the Department of Justice people including the FBI. "I also work here," he said--because J. Edgar Hoover was practically his boss!

Later on some of the guys decided--there was this legislation and activity about forming unions, organizing civil servants. I come from a fairly liberal background and I figured, well, it's my duty. I should join. I joined. Some of my friends didn't. Some of them whose parents and relatives had been organizers of the AFL (the American Federation of Labor)--they were afraid. I and some others joined and then the boom began to be lowered. One of the guys who worked with us had a son who was a problem case. He would never amount to anything, his nerves were all shot, so his father, who worked for the FBI, would never have anything--only expenses. He was the first one who was invited to resign. And then, one by one, the members of the union were forced out.

Q: Now what did they say to you? What grounds did they use? I mean did they just tell you that they wanted you out because you were a member of the Union, or did they have to find some pretext.

Borgen: No. No. Oh no. I was told that I wasted too much time. I don't remember what else, if anything.

Q: Now this was a mass thing. A lot of people lost their jobs.

Borgen: Many, many of them...

Q: And they ended up at Social Security.

Borgen: Yes, at Social Security.

Q: Which is very interesting. . .

Borgen: Oh yeah. . .

Q: Because I've seen in the history files these job applications from people who used to have jobs as Fingerprint Classifiers--they all came at the same time.

Borgen: Approximately. Because we were kicked out one at a time. Norman Milburn, was a personnel man then, and of course I went to him and I wanted a transfer. He knew my story. He said, "Sure. Come on over. We'd love to have you."

Q: Now, he was at SSA?

Borgen: Social Security, yes--BOAI, this was before survivors insurance. They were recruiting for the Accounting Operations staff. I am now talking about September or August of '36, somewhere around there.

Prior to that--Oh here's another thing that didn't win me favor in the FBI. I took the exam for Special Agent. A Special Agent was a high salary guy--$5,000 a year.

Q: You were going to be an FBI agent?

Borgen: Yeah. You had to be a lawyer or an accountant. Some of the guys had got together who had just gotten out of school and we felt we ought to take the Bar. Some of them were members of the Bar in their home states but I hadn't taken it. I just graduated from school and I figured I didn't need the Bar. I'm never going to get anywhere in the law profession. You can't visualize the situation, in the 1930s during the Depression. The idea of my being able to make a living, when I had this sure salary with a retirement and all. I was persuaded. I took the Bar. I passed the Bar so I was a lawyer and I think the FBI required you to be a lawyer and a member of the Bar to be Special Agent.

Q: So you applied to be a Special Agent? What happened?

Borgen: They gave exams. I took the exam. I thought I did pretty well, but I didn't make it. I got a letter saying I didn't make it. Try again. I wrote Mr. Hoover a letter in effect saying, "Don't kid me. No use in my trying again. You're not going to appoint me anyway, for a number of reasons." I didn't think I mentioned them, but that was the tone of the letter. In fact I'm sure that didn't sit well with him. My implication was "Brother, you are a bum." That's what I was telling him. I didn't trust his invitation to take the exam again. I wasn't going to be a Special Agent if he could help it.

And then I ended up with coming to Social Security. I had all that added incentive, plus the FBI request to please depart and close the door behind you. And at OAI I met a lot of the guys from the FBI who were already working there. I was assigned to the Correspondence Unit.

Q: Now did this job at SSA pay more or was it just people who were being pressured?

Borgen: Some just wanted out of the FBI in any way. Some of the guys who didn't join the union--they left on their own. They were not forced out.

Q: I've seen files on dozens and dozens of people who came over from the FBI, from this job that you had.

Borgen: And thereafter, when Social Security appropriations were up before the committees in Congress, Hoover had his man there with some proviso. None of this money shall be spent for the salaries of any of these guys who were radicals, communists, or lord knows what. But the Bureau of Old-Age Insurance was fairly liberal, and they knew what they were doing. They hired us and I think we made Social Security pretty much what it was as intended by the legislation. We got it going.

Q: So late 1936 you came over and interviewed with SSA and they offered you a job in Accounting Operations.

Borgen: Yes. Well that was before the account numbers, they were recruiting to set up in the Candler Building all those large accounting operations--punch-card operators, and everything. I heard that it was supposed to be the largest single recruitment in the history of the federal civil service, to put Social Security in the Candler Building. Thousands were hired. I was assigned to the Correspondence Unit, to answer inquiries and all that sort of stuff. There was a whole staff in DAO for this.

Q: You were in the Candler Building?

Borgen: In the Candler Building. I knew an awful lot of young people in the Candler Building. My wife was recruited from her civil service exam. She took a statistics exam and she got in and what she did was classifying, with a lot of others, when they set up the records, the punch-cards and so forth, and identification, the SS5s and all that, the employer identification numbers and so forth.

Q: Had you lived in Baltimore before that?

Borgen: No.

Q: So this is all new. This is the first time you had come to Baltimore.

Borgen: Yes. I was living in Washington, and I had to move to Baltimore. They told me to report to Market Place. The night before I packed up my suitcase with all my belongings, came to Baltimore. It was pouring cats and dogs and at the station (B&O Station) I took a cab. I wanted to go to Market Place, wherever that was. Oh, no. I wanted to go to a hotel near, very close to Market Place. I didn't know Market Place from a hole in the ground. The cab took me there. It was the Hotel Louie in the Block. (Editor's note: The Block is a notorious section of downtown Baltimore famous for its "adult entertainment.") That night was a restless night. But I slept.

The next morning I went down to the Candler Building and signed in and got my place and I moved out of the Hotel Louie and moved to the Knights of Columbus. The Knights of Columbus also had rooms for rent. It was a decent place in mid-town, and I lived there for a long time, until I got to know the city, and then I moved up to North Avenue near Druid Hill Park. I think it was 800 West on North Avenue.

BOAI was bringing in so many kids, housing them got to be a real problem. And there my ties with the Union got kind of tenuous. Of course I was very much impressed by the Personnel Office, and the others, and I thought they were fine people and they were doing a swell job. Some of the other guys, I suspect, were really left wingers and those were the days when there was a lot of boring from within--Fellow Travelers, and all that.

Q: There was a lot of sentiment in favor of communism at that period. It was almost a mainstream sentiment.

Borgen: Right. All the college kids--this was the way to go. The people I mostly associated with were Norman Thomas followers--Eugene Debbs, Norman Thomas types. The communists had no use for us. We were fools or fakers because the real way to get heaven on Earth was through the communist principles, and we were socialist types fooling the people and so forth, or we were fakers. The conflict was great.

Q: Now while we're on this subject of the political climate, how would you characterize SSA as an organization? You alluded earlier that it was a fairly liberal sort of a place, that it had a political orientation that was liberal. Is that a fair description?

Borgen: I think so. I think Roosevelt really reflected the sentiment of most of the people, of most of my friends anyway, and the general attitude reflected that. It was sympathetic to labor and organizing and getting a fair wage, getting employment--all the things that Social Security was going to do. This was a great place. Morale was sky high. Everybody was doing his best.

But of course some thought it wasn't good enough, and I used to have long talks with those guys--the real left wingers and I would clash. We would take long walks and I would try to persuade them, and they would try to persuade me, and these were mostly within the union. One of the guys (a very bright young fellow, Bernie Schultz, fat boy, round face, very bright--also CCNY, I was CCNY too) came to me one day in my room and he said, "Herb, I've been invited to join the Communist Party. What should I do?" I said, "Bernie, they'll kick you out so fast you won't know what hit you." He was a very independent guy. He was a good man. Bright and intelligent and imaginative and he had his own ideas. I said, "Bernie, that's a party of discipline. You wouldn't be able to stand them." And I knew from experience because I was always arguing with them. They were nice guys, but they were misled or something. I couldn't understand their mentality. We were all working for a goal, with Social Security, for the betterment of people in general. But they went their way and the socialists went the other way. Roosevelt was closer, I would say, to the socialists and farther from the communists than even the socialists--and that was the prevailing spirit.

Q: So the people who worked at SSA in those early days had a sense of a mission and a sense of the importance of what you were doing?

Borgen: Strong. A strong sense.

Q: They were philosophically committed to it, is that right?

Borgen: Yes. But Bernie got into trouble. I think Bernie--I don't know what happened, whether he joined or not. But I do know that within the union, when there was trouble, for instance, in Spain and the Soviets were organizing, some of these guys with whom I was in constant argument, they'd hold a meeting on events in my apartment. We were like an executive committee, self appointed. Leaders, you might say. These guys wanted to pass a resolution--by the union group in the Candler Building--to support Russia or the Russian position. It was stupid. But generally they would prevail in the debates due to their force and their discipline and their energy. But most people liked the idea of Social Security--at least we thought so. But they didn't drive; they didn't have the push. I'm talking in general--not the employees. The employees were ok for Social Security.

Some of these guys met with their fate later on. I never heard any more from Bernie. Oh, Bernie got into trouble. He was one of the brightest guys I knew. His assignment was pulling paper clips and Bernie couldn't do that all day, and he managed to get into trouble. So he was brought up on charges. They were going to fire him. Actually he was breaking the rules. And he was defended and they had hearings in the Candler Building and so forth. I don't know. He transferred out. I think he went to work for the Civil Service Commission, where his brother was already there as an examiner. I heard no more about it.

Years later (I was married and had a child and so forth) an FBI guy turns up. Do I know Joe? Yes, I know Joe. How well did I know him? Did I ever visit him at his home? Does he visit in my home, etc., etc.? I told him what I knew about Joe.

Q: Now this was in the '40s or the '50s?

Borgen: In the '40s.

Q: Ok. Before the war, during the war?

Borgen: It must have been. . .well...I skipped a couple of steps in between.

Q: We'll come back. So they were investigating these guys because they were Communists or Communist sympathizers or something. That's the idea?

Borgen: Right.

Q: Alright. Let me ask you just about the Candler Building.

Borgen: Let me just finish this story. There's a quick conclusion. I called this guy Joe. "I was interviewed about you." I told him what I said. He thanked me. The next morning I went to work. He had resigned. He went to work in a carpet factory or something. He had come out of the FBI. I knew him from the FBI. I knew his position. I didn't think he was going to overturn the government and I kept arguing with him to try to get him to see the light, that he was so far off. We would discuss current events and differ on them and I felt an obligation to tell him. I told him. Some of the guys who came over to OAI were that way. Others were afraid, I think afraid, where they figured they'd get ahead faster if they didn't join the Union. They came over. Others came over at the invitation of Mr. Hoover and so on, and that was quite a group. Now, where am I?

Q: Tell me a little bit about the Candler Building, what it was like. Did we occupy the whole building or just some of the floors?

Borgen: No. Some of the floors. I believe it was some of the upper floors.

Q: It must have been a huge operation though.

Borgen: Yes. All the Social Security account number cards were filed there, etc. At first there were no monthly payments, just lump-sum payments. The original Social Security Act was a very short little piece of paper. If a guy died and he had made his contributions, you see contributions began in '37, and he died before the effective date for monthly benefits, his estate had a right to a return. Tricky. We followed the laws of the state in which the guy was domiciled, a resident. That's quite a few states. The estate, the widow or the administrator, would file a claim. So there had to be claims forms and a whole procedure and there had to be adjudicators. During that period when we were making benefit payments, you might say, lump sum payments of 10 cents, 65 cents, big payments, but in that period we were developing our concepts and our legal procedures of how to handle these things.

Q: How to take a claim, how to process a claim.

Borgen: And everything had to go through the General Accounting Office, every form and so forth. We had the award forms that were about this long. We must have had about 15 or 20 items on it--the earnings, the name, the address, the beneficiary, the computation. And often, for instance, if the name on the SS-5 was Joe A. Bloke and the death certificate said Joe Adam Bloke, you had to make a finding, a special finding. Joe Adam Bloke and Joe A. Bloke are identical, by hand, hand-printed in triplicate--time consuming, oh. (This applied also to denial decisions.)

Q: Everything was by hand, right?

Borgen: Oh, everything was by hand. This was after I got out of the Correspondence Unit...

Q: Now that's what you did in the Correspondence Unit?

Borgen: No. No. That was before. The Correspondence Unit was when cards were first being assigned, when account numbers were first being assigned and people were raising questions.

Q: Ok. What kind of questions would they be asking?

Borgen: Who remembers? But we were foolish. We were kids. Inexperienced, is the correct word. All of us with college degrees, writing letters and--we used sesquipedalian words. So we had to be turned around--it got to be a real problem. Years later...

Q: So you could write in a simple language?

Borgen: Yes. So we had to learn to write in a simple language, so you could understand it. Don't try to show how smart you are, and don't be too damn technical. Later on, in Washington at the 18th & H Street Building, John J. Corson (he was great at reviewing the correspondence), he reviewed almost everything. At that time I wasn't in Correspondence, but I knew what was going on. He said, "Stuff should be written so that the newsboy downstairs in the building at Social Security, a guy 12 years old, could understand it. Bring it down to his level." That was a continuing struggle.

Q: Ok. So you worked in the Correspondence Unit...

Borgen: Then I transferred to--I transferred and a whole flock of others--into Adjudication.

Q: Now were the records on those big ledger sheets and stuff? Tell me about that.

Borgen: I don't know. I wasn't involved with that, although we had to use them to adjudicate the cases. I was in Correspondence and then I was in Adjudication.

Q: Alright. Tell me what you did.

Borgen: We were broken down by regions. This group handled all the claims coming from Region II, and so forth. Essentially it was fairly routine, going over these papers, and filling out these forms. And then the volume increased and we were moved to Washington.

Q: The Adjudication Unit.

Borgen: The Adjudication Unit, including all the regional groups.

Q: Do you remember what year that was?

Borgen: No.

Q: Ok, so the Adjudication Unit was relocated to Washington.

Borgen: To Washington.

Q: Because they needed space in the Candler Building or...?

Borgen: No, I don't think so. It could have been that, I suppose--I really don't recall. They could have found places in other parts of Baltimore.

Q: The administrative headquarters had been in the Washington all the time. Accounting Operations was in the Candler Building. So did you move back into the building where the rest of the Headquarters was or into a different building?

Borgen: No, a different building. We moved into an altered old apartment house, pretty far south of Constitution Avenue. Right near a very big apartment house, a big, very fancy, apartment house that was used as an apartment house, which was later bombed down. And that site became the State Department building. Back then, it was the residence of a lot of the guys who were working in Adjudication, and where we were working was just a block or two south of that. But we were just a few blocks from other SSB divisions.

Lou Lang headed Claims Policy. Now I headed a little group of--I'm talking now about 1939, after the '39 amendments. We were paying substantial amounts now. George Keating headed the region, the Adjudicative region. We were broken up into units. I had one of the units. There were ten or so adjudicators and then I had--I gave you the picture of my reviewers--Tom Parrot was one of the guys, and I headed that group. Lou Lang, Mercia Leton, and a couple of others were working on Claims Policy.

Q: Ok.

Borgen: We had a lot "fun" interpreting the rules that we were following. I received a card, I don't know why or how, from some congressman, maybe a New York congressman--in those days I voted in New York on absentee ballot because I was still a New York resident. They were going to hold a hearing in the committee (I forget which committee) and I was invited to attend as a witness if I wanted to come. I discussed that with Lou Lang. Lou Lang headed the Policy group and I told him, "Lou, my feeling is that we're wasting a lot of time filling out these damn forms. If we've approved the application you can simply get a simple form to indicate you approved it, stamp it, sign it and out it goes. You don't need all this massaging."

Q: These forms were kind of like a record of all the decisions that had already been made on the claim? Is that correct?

Borgen: No. This was the allowance decision, with all the required findings on which it was based. This allowance decision went to some Payment Center for processing and it got entered into the Treasury Department on the rolls. It went from here to the rolls--benefit rolls. Lou Lang taught me something. I was learning, actually, all along. If I had the knowledge and experience that I have now back then I would have been able to do better. You know what he says to me (when I told him about this idea, the simple form, you know), "But you know what that would mean to the size of the staff?"

Q: So he didn't want to do it?

Borgen: No. No. He didn't...He put it a little more forcefully. "And you know what we would do to you if that's what you do to us?"

Q: So he didn't want you to go to the hearing and suggest that?

Borgen: I did not go.

Q: How did you get an invitation to the hearing?

Borgen: I don't know.

Q: And that's the kind of thing they wanted to find out?

Borgen: I don't know. They were going to discuss Social Security, what aspect I don't know. I don't know, but I thought I had a great idea to simplify things. Like the idea in these recent days, the post card IRS income tax form.

Q: So after the '39 amendments passed and we started paying monthly benefits in 1940 I assume the volume of these cases picked up quite a bit.

Borgen: Oh, let me tell you another experience. With the 1939 amendments we had already decentralized considerably. I think the Payment Centers had already moved out. At any rate, it was decided that the central office people who are writing the rules--I didn't do claims policy initially, eventually I did. From Adjudication I went to into Claims Policy and there we had to write the rules, various rules. At various points I was involved with the rules on parents' dependency, proof of age, a whole flock of burning issues and that's where I worked with Gus Myers and a whole flock of other guys, great guys. We developed the procedures. So along comes somebody from on top, from the clouds, and says the field people are unhappy. They think the nuts in central office don't know what is going on. They ought to get their feet wet.

So from time to time we were sent out to work a day or so at the field office. I landed in Harlem. It was just a wonderful experience. It really was meaningful. I would say that one of the many wise things Social Security did was to get the central office people in the ivory tower to get down to the grass roots and see how things work and what the problems are. And did I see problems.

For one thing there's a racial problem. I had no problem. At one point the Claims Policy Division, Ewell Bartlett, was thinking of recruiting a black man to work in Claims Policy and he asked me, he says, "I know you guys are liberal and so forth. How would you feel if I hired him." I said, "Fine. No problem."

There I was in Harlem and I was told the field rep would go out to make contacts for Social Security numbers, to answer questions and explain things. I was advised to be very careful. In Harlem if they think you're an investigator, a welfare investigator or something like that, you might get hurt, so I was cautioned. Nothing ever happened. Nothing to support those fears, but I think it's interesting. That was the perception among all the field people, the Social Security people in the field office--Social Security employees. I was white, and I think there may have been some other white guys there, but we were told to be careful even going in the streets there.

A crowd of women came in at one point. They're going to apply for Social Security numbers. They're giggling and laughing, and I asked them "where's your employer?" "Over there. In that building over there." More laughter. I asked one of the guys what was going on. He said, "That's a whorehouse."

Q: And they wanted account numbers for their employment?

Borgen: Right. We gave them account numbers. They were treated like anyone else. But I was just surprised. I mean it was a novel experience.

I had another similar experience. An old lady comes in. She wants to know about her earnings record. The field office had send out a request and received the information. She came in for an explanation. She said, "Why is it that in the first two halves (they used to report earnings semi-annually) I got so much and then after a while it stopped all together, but I've been working steadily, I've been doing the same thing." I said, "Well, that's a fine howdy do. I can't explain that. Let's go talk to your employer." This was around my school on 116 th Street. Columbia University. I went to law school at Columbia. Columbia had a very famous School of Journalism, among other things. In that area there were a number of real fancy homes that were no longer being used as single family homes. People were renting rooms. So students would have rooms there. She worked in one of those houses. So I went with one of the staff people, a black man. I knocked on the door and a lady comes and looks, sees my colleague, shuts the door and goes right back. Then she comes back with the mistress of the house, she opens the door and gives us a sour look. "Come on in. What do you want?" "We were wondering about the earnings reports." "I've taken care of that. You guys, Internal Revenue have all been here. The state revenue people have been here. I've explained it all." I said, "We'd like to discuss it with you." We go in. She says, "Sit here." We sit and I see where I'm sitting, it's a room about living room size. There's a bookcase and I think there was a piano there. From what I could see it was a piano and the lady explained. "My brother is a Wall street lawyer and he has incorporated us as a charitable institution, exempt from Social Security taxes. And that's why I stopped paying Social Security taxes."

Q: So this was her maid or her housekeeper or something?

Borden: Yes. This was her servant.

Q: And she stopped paying taxes?

Borden: Yes. So I asked, "So far as I know she's doing the same work, what's the nature of the change?" "Oh, we have quarters for impoverished southern ladies. This is just for women who want to stay here and they can't afford it; we have a room for them. We give them a room. We also provide theater tickets." I knew about the theater tickets because in the summertime I'd get a summer job at the theaters during the Depression (we were in pretty bad shape) and a lot of tickets were handed out to fill the seats. So she'd get a lot of these tickets and she'd hand them out with no charge. And those kids could have gotten them on their own. "And there's a piano provided for them in which they can practice, and I have a library and they can borrow the books, and we're a charitable organization and it's been approved." So we say, "Well, where does your brother work?" "Downtown." "Ok. Thank you."

And off we go. I excused myself from Harlem. I said, "I'm going down to the downtown office." I went to the downtown office. I get one of those guys (you dealt with one of the field reps). I go with one of the field reps. We go into this law office, a real swanky place. We ask for this guy and he comes around and says, "Yes. This is what it is and we've gotten the New York state approval," it is a charitable institution. That's it." "Ok," I said. "I have all the information I need."

Eventually when I got back--we had a Coverage Section in Policy. I said, "Can we get after these guys?" Our policy had gotten to be that if the employee could establish that she was paid a salary, and we were satisfied that the place was covered, they get the benefits even if it did not appear on the wage record --we treated it like a correction. But if this is a non-covered unit, how do we work this out? Well they have to work this out with IRS, and they were very unhappy in the Coverage Section. They got a few of these, quite a few of these. Internal Revenue was not very cooperative because what they would have to do is spend a lot of time and manpower to collect a few cents. They wanted to go after the big guys. I said, "But this is an injustice. This gal's retirement is threatened. She's an older woman and she's going to retire." Well they worked on it and they worked on it and I kept after them. Did they do it? Did they do it? A long time later, Internal Revenue got it straightened out. She was going to pay the tax. They were not exempt. So that was the sort of thing that you couldn't forget.

One other story. I went out with a Claims Rep into Harlem for a claimant. He was retired, an old man in Harlem. We go up to this poor apartment. Spotless. Clean. A very nice old guy, real old, handicapped and so forth. He applied for retirement benefits, and also for the wife's benefit. "Where's your wife?" "In bed." She was bed-ridden. We went to see them--black people. And the Claims Rep began taking the application from her. At one point he asked, "Were you previously married?" If she said she was previously married, of course after that you'd have to say, "What happened?" He asked the question, and there was silence and discomfort. The air got a little sticky. He wrote "No" on the application. Then we went along and I said to myself, well, that's life. I knew from experience that those who said "Yes," and then had to show that they were legally divorced had problems, a lot of the people down in the south, they didn't know from legal divorces. They thought if you jumped over a barrel or you went under the moon or something like that, you were legally divorced. They would never have been able to establish it. I thought that was fine.

We had similar problems all over--proof of age, proof of parents' dependency. I did a study on proof of parents' dependency. Often if the parent was on a farm and a large part of his income was from his horses and his cattle, his dairy, his milk and so forth, it was hard to say what was the wage earner's contribution. The guy supplied, among other things, he would supply some of the feed for the cattle. We had to figure out whether more then 50% of the man's support came from the child. How much feed did he supply for the cattle? That sort of stuff. It got to be...if you were going to play by the book, you're going to be ridiculous. If you're going to insist on dotting each "I" it would be impossible. But if you're going to relax it too much, it would be giving the government's money away. So it was hard. I learned a lot, and I suppose a lot of others did too. I'm mentioning these because I suspect my experience could not have been very different from that of many others.

So, I was in Claims Policy, and then I'm working on guardianship and so forth. We had the problem, when you're paying somebody and somebody's incompetent, whether it's a child or Alzheimer's or what have you, how do you do it. Well, we developed rules on guardianship. We insisted on guardianship. How enforced that ever was I don't know. But we would insist that the payment was made to the guardian on behalf of so and so. Supervision of those things was questionable.

Well a lot of things in between. The war came and the guys began to be drafted and some of them went off and never came back and some of them were very unhappy with military life. I remember one of the guys who came back after the war and was assigned to the Chicago Payment Center. One day he didn't show up and he was very unhappy. They went to his apartment to see what happened. He hung himself. He committed suicide. There's a lot of stuff in guys coming back. But there was also a lot of talk about disability. Well before that, before disability... Let me see, what do I have here. Civilian war benefits...

Q: Yes. Tell me about that. Tell me what that was about.

Borgen: Well, the President was given emergency funds. He allocated, I think it was about $5 million, to the Federal Security Agency to set up provisions for air raid wardens, auxiliary policemen, auxiliary firemen, civil air patrol and that sort of stuff--people injured in the performance of their duties. And for the widows and so forth if they were killed, and for the payment of their medical care, because the Public Health Service was also part of the Federal Security Agency. I did not set up the office. I don't think I was involved in that. I just don't remember how it happened. My involvement was just on the periphery, I suppose.

We established a joint office, familiarly known as "the joint," in the Equitable building on the top floor. And we wrote up procedures and policies together with physicians detailed to us from the Public Health Service--Thomas B. McKnealy and Dean Clark. Wonderful guys. We agreed that questions of eligibility would be OASI's job, Milt Mayer, Gus Myers, and me, and we had a staff. Mostly we were writing procedures and forms and stuff and working with these two doctors as to how we were going to actually operate.

Q: Now were these benefits that we paid under the regular title II program or this was...

Borgen: Out of the emergency fund allocated by the President. I don't know if Congress even knew about it.

Q: Ok. So this was a different benefit program, a temporary war benefit program.

Borgen: Temporary Civilian War Benefits.

Q: And the eligibility for these benefits was similar to Social Security or had no connection?

Borgen: No connection.

Q: Ok. But you all were in the Federal Security Agency you got...

Borgen: We were in the Federal Security Agency. We had the machinery for checking on identifying people. We were accustomed to doing that, taking these claims on a volume basis. We had machinery for referring to Internal Revenue, getting people onto benefit rolls, and we had the space. We had office space available in Baltimore.

Q: Ok. So now this paid benefits that would be similar to Workmen's Compensation or...?

Borgen: I'll give you a case. Yes. It was very similar to Workmen's Compensation.

As a matter of fact, in anticipation of all this, actually long before this, I got involved with disability planning, I figured this was likely to happen. Social Security was talking about disability benefits. It was in the papers. They were talking about how it would be nice to have disability benefits insurance. So I figured I'll read up on this. I'll study up on this and so I studied what I thought was relevant from Public Health Service reports on disease and disease identification, incidence rates, prevalence, types, etc. And there were books on Workmen's Compensation, text books--lots of them. And the International Labor Organization (the ILO) connected with the United Nations at the time, would issue material on government Workmen's Compensation programs throughout the world. And there were authorities in the universities who wrote law articles. I delved into that and I think in the process I got to feel that I had a more comprehensive view than a lot of the guys who were assigned to do the work--the guys who were doing disability planning.

Gus Myers (who's picture is there) had worked for Ms. Perkins in New York state when she was head of Workmen's Compensation there. So he was experienced in Workmen's Compensation and he had the workmens' compensation attitude--he didn't trust anything. We'd get into some terrific debates (Gus and I). One time Gus comes into me (I was working on some of these things we were doing on planning; I don't remember what aspect) and he tells me, "You're wasting time on this. Why don't you do this." So I asked him--I used the Socratic method on him--"How would you do this? But if you do this would you do that?" At the end he came out saying just the opposite of what he came in with and he went out crest-fallen. Later Milt came in and said, "Herb, you shouldn't have done that to Gus!"

I'll show you the type of case we had, one claim--I'll give you two claims. They're both interesting. I'll stop with two. A guy, a husband of a woman who was going to be a nurse's aid in the civil defense (you know they practice bandaging and they had meetings and all that). He was a volunteer. So the group there they bandaged him up and so on. It was outdoors. I think it was a actual air raid siren. They were testing the sirens. Were you around then?

Q: No. That was a little before my time. I was born in 1949. But that's alright.

Borgen: Yes, that's alright. I guess it's hard for me to appreciate that, you know? I assume you know these things, that you lived through them.

Q: No. I know some of them just by reading about them.

Borgen: Yes, well that's how the knowledge passes.

In any case, I'm sure it was a siren because all of the lights were out. The windows were shielded. Air raid wardens were going around to make sure all the lights were out. And so they ran for the shelters--the nurses ran and they left him lying there bandaged in the alley where he was. A truck was coming through. He couldn't move and he couldn't yell. He was hit by the truck and was badly hurt. Well, we had a problem. He was helping out and so forth. We allowed the claim. We found him eligible. The doctors signed the forms for their part. They took care of the medical expenses. If we said he was eligible they paid and we took care of the benefit rate. I don't remember how that was set up, frankly.

Q: So this program even paid medical care long before we had Medicare or any of that? We were paying medical care benefits...

Borgen: Yes. Yes, right in the Equitable building on the 8th floor in Social Security, staffed by almost entirely Social Security employees and a doctor.

Q: How interesting.

Borgen: The doctor's desk was here. My desk was here. Cases came to us first to make sure he was eligible and the doctor didn't have much to do. He just got the medical reports. Of course we had the medical reports. Field offices developed those claims. We told them what to do. There were so few of them there was no manual. We instructed them if they had to make contacts, Public Health Service might have used some of its contacts. I don't know. They made out their forms, where they worked, how much they were paid, the hospitals where they were treated, or whatever.

An interesting problem of eligibility came from the Aircraft Warning Service. A fellow was stationed out on the coast in the Carolinas, I think, and he had to watch airplanes to see if by configuration it was an enemy plane or something like that. And, of course, he didn't have toilet facilities in these isolated spots--the mountains and beaches. He had an outhouse. He went to the outhouse. He was bitten by a spider. It was a serious one. Some poison got into his system and he was really sick and there's no question about his being disabled and so forth. But was he eligible, because we required a war-related trauma.

Q: So the question was, is a spider bite a war-related trauma?

Borgen: Yes. We took that up with the Social Security Board. We allowed the claim.

Q: Good. That's very interesting.

Borgen: One sad one was in Alaska. Auxiliary fireman dragging a hose, practicing. He had a heart attack, attributed to carrying the hose. Well there's a lot of conflict on that but the doctors decided that it was work-connected, that we could find a trauma and eligibility--there was no question. Those were the kinds of problems that I remember.

Q: And did that go on all during the war? It lasted until the war was over?

Borgen: Before the war ended. The atomic bomb had not been dropped, but it was obvious Japan was licked. Germany had already surrendered, the European front was over. Our problem was just the Pacific. We were not going to be getting any more claims, so what do we do? I thought Social Security should give up this program. We shouldn't want to keep it because it would be a program in which there would be nothing new coming in and disappearing caseloads.

Q: But you were paying regular benefits, monthly benefits to some people?

Borgen: Well, the Treasury was. The roll was set up. What do we do with this? Well I knew the Employees Compensation Commission also administered the Long Shoremen and Harbor Workers' Act. They also administered the District of Columbia Workmens' Compensation. They also administered the Panama Canal Workers' and a number of other small programs. The program was dying out, was dwindling, evaporating. I figured that should be their home, especially since the Bureau of Employees' Compensation was also under the Federal Security Agency. So all we had to do was get the Social Security Board to agree, so we had to take it up with the Captain (Captain Watson--McNutt's right-hand man). We went down to his office and we gave him the story and he said "yes." So it was transferred. Congress had nothing to do with it.

But in the process, in our experience of operating this program, we did develop contacts with a variety of disability programs. We did work out a disability ratings schedule, because we were paying partial disabilities as well as total, and temporary total as well as permanent total, and all that sort of stuff. I turned over all those papers in that big box that I gave to Linda David. Some guy came down and took it and I don't know whatever happened to it. Some of the stuff I turned over to the Bureau Library there. I don't know. They may have thrown it out.

Q: I brought a couple of things to show you. I found some things finally. Here is a copy of the disability rating schedule for Civilian War Benefits program, from December 1943. I have the original but this is just a photocopy.

Borgen: I don't need the original. May I make some comment about this.

Q: Please. I want you to. That's why I brought it!

Borgen: Some of the differences between this rating schedule and what we had in disability insurance programs. For one thing, this provided for temporary total disability. In other words there's a trauma, an accident. The guy is laid up, but he's going to recover. He's not going to be disabled permanently, and he's going to recover. In the meantime he's out of work, he's getting medical care. That was covered both in the medical care provision and in the disability benefits, at the same rate of total disability. If when his condition stabilized he had a partial disability, if the partial disability appeared to be permanent, then we applied the rating schedule. We do not have that at all in Social Security. In other words the disability insurance is total, and the expectation is it's going to last way into the future--be permanent. So in the Civilian War Benefits program we were actually following very closely what the Veterans Administration did.

Q: The way they did ratings?

Borgen: The way they did their ratings, yes. There are a number of problems that you have with this, that we wouldn't have in our program, because a fellow may have more than one partial disability. You don't add the two numbers together, but you had the schedule of combinations.

Q: But you had a table...but we considered multiple impairments.

Borgen: Oh yes.

Q: And added them together.

Borgen: Added them together. Or they reached Temporary Total at 100%. And there had to be injuries, generally traumatic. No occupational disease like "black lung" and so forth. When they stabilized generally as Permanent Partial we could generally apply the schedule.

Q: Did you participate in putting together this schedule?

Borgen: Oh yes.

Q: And I saw a reference somewhere that ORS (Office of Research and Statistics) had helped with this schedule, that BOASI and ORS somehow together worked it out...

Borgen: I don't remember now what their role was.

Q: Tell me what you did to put this together. How did you do that?

Borgen: We had the advantage of cooperation from the Veterans Administration. We had access to their rating schedule. I believe in those days their rating schedule was confidential.

At this time the Railroad Retirement Board also had its disability insurance program. Well, they had the equivalent of Workmen's Compensation, and it's the same thing. We also had some reference to the experience of Long Shoremen and Harbor Workers. These were all federal programs so we felt we were on a pretty stable ground.

Now what Gus Myers and his bunch in Claims Policy (OASI Claims Policy) contributed, I don't remember. It probably was the participation of the field offices because we did not have any special field staff in the Civilian War Benefits program. The fact that we had the field organization covering the entire country made it particularly suitable for Social Security to handle this program, getting forms filled out, explaining the program and all that sort of stuff. They got the evidence together and forwarded it, got the Social Security number and I believe to some extent we used the earnings records.

Q: The way it looked to me from what I read was you had to establish earnings because the payment amount depended on earnings and we used the earnings record, if that was available, but we used other things like pay stubs or whatever.

Borgen: That's right, because a large number of civilian defense workers were women who had no earnings records at Social Security. I don't remember how we handled that. I just don't. I know at one point the Social Security feeling was that homemaker was an occupation and that some credit should be given on the wage records for that for a variety of reasons. But I don't know how we handled those individuals. Their medical bills were covered through PHS after we determined eligibility.

Q: Now in terms of some of the dates, it looks to me like the "Joint Office" that you talked about before opened in March of '43. That's what I think. Now the original letter that President Roosevelt sent to FSA with the $5 million from his Emergency Fund, he actually sent that letter in February of '42 and in that first letter it didn't cover civilian defense workers; it just covered people who were overseas...

Borgen: Sea Bees, Wake Island...

Q: Sea Bees, Wake Island. Exactly. And then in October of '42 he extended it to civilian defense workers and people in the country. Then in March of '43 you opened the Joint Office and paid your first disability claim and then it ended in June of '45.

Borgen: And you know how it ended. It didn't end. It was transferred.

Q: Right, but we stopped taking new claims.

Borgen: We stopped taking claims. The material, the old claims, those who were on the rolls, all that material, was sent over to the Bureau of Employees Compensation. It occurred to me you may want to call the Bureau of Employees Compensation and say, "How's it doing? What's happened to it? Are you still there?"

Q: That's a great idea. I should try that.

Borgen: I'd like to know how it's being funded.

Q: Yes. Me too. And do they still have beneficiaries?

Borgen: Well of course. I'm sure there are widows.

Q: Yes. I better check. That's a good idea. Now did you come into the program right there in '42 or did you come in when the joint office was set up in '43?

Borgen: Gus Myers and Milt Mayer both worked in whatever disability was being formulated, early on. Their experience had been with Workmen's Compensation in New York. Certainly Gus. Milt, I don't remember what his background on this was.

My background, I told you. I decided this was an interesting field. It was a vacuum before the war and I read Social Security was thinking about the extensions to the program--old age, survivors and disability. I thought it would be a good idea to learn something about the experience in Workmen's Compensation, the International Labor Office (the ILO) and their experience internationally, the German experience, French and so forth. And then there were academics who wrote about evaluating disability. And there were books on malingering and all that, related to Workmen's Compensation. In doing all this I picked up a lot of stuff which I'm afraid none of the other guys had. They knew their experience in New York.

At any rate I got in with them and we started (I don't remember the date) formulating an organization and a program. In the planning, I don't remember the participation of the Public Health Service. Their doctors, McKnealy and Dean Clark, were available and we knew they were going to pay the benefits but I don't remember how the inter-organizational setup was agreed upon. It was agreed upon to a large extent that Social Security (we) would make the decision as to whether the individual was a civil defense worker, establishing his eligibility as a properly covered person, establishing whether or not the injury was in the performance of his duty, whether it was traumatic, etc. We made the final decision and determined the amount of benefit, and whether he was entitled to the benefit. It wasn't clear to some of the doctors, who came to help us at various stages in the actual working after this was set up, as to who decided that it was total disability or partial disability. Who had the responsibility and the authority? That almost lead to blows between Chuck Hayden and me. His said "this is total disability." I said, "Well that's our decision." Is he able to work? How does this fit in? You notice this rating schedule is almost all partial disability--relates to partial disabilities.

Q: But there must be something about total disability. Here, for example, it shows presumptive cases where it's presumed to be 100%...

Borgen: Well, in the history of Workmen's Compensation this isn't even a question--there are some cases were the person is totally disabled, without the slightest doubt. Anybody who loses both feet, both hands, a combination of the feet and hands, becomes blind, any such disability which requires the individual to be permanently disabled--that really never got to be an issue. It was never an issue.

Q: But we did have these categories, these presumptive disability categories.

Borgen: Yes, we used the presumption.

Q: Ok.

Borgen: You see there is no work clause here as I recall it. There is not a retirement test.

Q: Right. Ok. Not substantial gainful activity or any of those concepts...

Borgen: This was not an air-tight arrangement.

Q: Now let me see if I understand the process. Somebody's out in Paducah and in Paducah they get...

Borgen: Let's take in Muleshoe, Texas.

Q: Muleshoe, Texas. Working in the civilian defense program and they become injured in line of their duties, the local DO...

Borgen: They go to the field office, the field office takes a claim. The Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) did all the public information work as did CAP & AWS--to care for their volunteers.

Q: They take a claim and fill out a form (and I have copies of the form I'm going to show you in a second and we'll talk about that).

Borgen: Very good.

Q: ...and a local DO would also collect medical evidence from the doctor there in Muleshoe.

Borgen: Help the guy, yes, ask the fellow to get it and so forth. They've got to release the evidence. Otherwise the doctor wouldn't give the information.

Q: Then they would ship that claim...

Borgen: To the "Joint."

Q: To the Joint, with the medical evidence. Now...

Borgen: It would come to us. We would get it, check his earnings record and all that sort of stuff...

Q: ...make sure he was a civilian defense worker...

Borgen: ...and the medical evidence...

Q: ...and the nature of the trauma...

Borgen: Yes, and some of these things didn't require anything. But some time there was a problem. We had a staff of adjudicators, they weren't fully trained, but they could recognize some things. If the doctor says this guy's two feet were amputated, we didn't have to consult the physician. Some of these other areas were more problematic. For example, elbow ankylosis. This is a condition which is caused by an injury where it's supposed to be flexible and it's no longer flexible, it becomes fused. So there were degrees of extension, flexion, supination, pronation. So in the listings we developed we showed different ratings with differing degrees of flexibility--180 degrees, 135 degrees. Sometimes there was a question as to whether or not this was valid, whether this was due to the injury.

Q: Or some preexisting condition. It might have been...

Borgen: They may have had it all along. He was working and he had this all along, so it had to be separated and the cause determined. We had to consult with the physician. That's why the physician was sent in. Also the medical bill. The district office would get all the papers, the documents where the guy would have had to pay the doctor and so forth. We turned those over the doctor.

Q: PHS paid that.

Borgen: PHS paid that.

Q: But in an ordinary case--in a fairly simple, straight-forward case--you would get the application and you would also get the medical evidence and you would make the disability determination.

Borgen: That was where we got into a fight. With this guy, Hayden. He didn't like the idea of a layman making that kind of a decision.

Q: Now was Hayden a part of your team or who was he?

Borgen: He was Public Health Service.

Q: He was the Head of the Public Health Service?

Borgen: No. No. He was assigned to us by the Public Health Service.

Q: Oh ok. In addition to McKnealy and Dean Clark?

Borgen: Well for the daily claims operations, McKnealy wasn't there. He and Dean Clark had moved out. They were in on the original planning and organizing. I don't remember the dates.

Q: That's alright. But the issue here...

Borgen: We had Hayden; we had Dr. Harolson. Harolson was a very interesting character. When he came into the office he would open the door and just stick his hat in. Stuff like that. Hayden was the one that gave us a problem. He and I went out to the hallway to talk pretty loud. I thought he would sock me. He was a big football hero type man. But I succeeded in explaining the different roles of professional and administrative functions. We became friends.

Q: Because he wanted to make that disability decision? He thought the doctor...

Borgen: Well you see he was also involved, either at that time or subsequently, with the health insurance program in Massachusetts. I think it was called HIP or whatever. It was in Massachusetts. And I suspect he was a little bit concerned about non-medical people (whom they like to call the lay person) making decisions which affect their handling of medical care, eligibility of medical care for payment, and so on and so forth. They were, like a lot of other doctors, a little suspicious and uneasy about Social Security being in this business.

Q: But the way it worked out is that you made the decisions..

Borgen: Oh yes. We made the decisions as to payments. We made the decisions as to whether or not the guy was eligible, was a member of the civil defense, and so on and so forth. The Public Health Service accepted that.

Q: But you made the disability decision too--disabled or not disabled.

Borgen: We made the decision. It had to be one, and there were no so-called "dissenting decisions."

Q: ...20%, 40%, multiple impairments. Unless it was a complicated problem, and you needed to consult with the PHS doctors...

Borgen: Well, what was complicated and what wasn't is a pretty amorphous concept. But they got to see all of these cases, because they were paying the medical bills. And we always got their opinions on all medical issues. By and large we had 100% agreement, sometimes after mutual exchanges of judgements on evidence and so forth.

Q: And if you made them eligible for cash benefits, that automatically made them eligible for the medical benefit too. I mean it was part of the same program...

Borgen: Yes. Because we made the basic decision that he was eligible. The Public Health Service really wasn't involved in that. Here's a saving clause. I didn't remember this. "Enemy action will" (I'm reading), "enemy action will ordinarily be a matter of common knowledge."

Q: Did we do in this program anything like consultative exams. If there wasn't enough evidence from the local doctor did we send for an exam?

Borgen: It was never a problem. I don't recall any problem about the acceptability of the medical findings. And I might also mention --I made a little note--we didn't have a reconsideration unit. We didn't have an appeals process. When we had a problem--I mentioned earlier the one with the black-widow spider bite...

Q: On the Carolina coast...yes.

Borgen: That went right up to the Social Security Board.

We also had one with a fireman in Alaska, pulling the hose with a heart attack. Well I knew from the Workmen's Compensation cases this is always a bone of contention, and we tended to be liberal. We felt we should be liberal and...

Q: ...nobody objected to that, basically.

Borgen: No. No. It's just that we wanted to have it settled and not just by us but as high up as we could go, which was the Board. We knew that in some programs causal connections between exertion and cardiac problems were bones of contention.

Q: Ok. Now I also saw a reference in here somewhere to an escape clause in these rating schedules and it said something to the effect that in case the use of the schedule would be--I can't remember the way they described it, but it would be an injustice or something--that it was possible to overrule the schedule and override the listing and make an allowance even without using the schedule. Do you remember any case where you actually used that escape clause, where you couldn't fit somebody on the schedule for some reason...

Borgen: I did not see all the cases. As a matter of fact, most of the cases went by without me. But here's what it meant. "An individual" (I'm reading) "shall be deemed," not presumed, deemed, "to be permanently disabled when the Board determines that he is afflicted with an impairment of mind or body which is permanent in character." The human body is awfully complicated and varied among individuals. Some degree of flexibility is essential. But the problem of keeping in bounds, as a practical matter, did not arise.

Q: The other interesting thing about this rating schedule is the first rating schedule was all on--what do you call it--muscular/skeletal. The first rating schedule was on the muscular/skeletal system, and there was some reference to the idea that later on you would develop rating schedules for mental impairments. Because that was more complicated and this was expected to be connected to some kind of war-related trauma, so you thought most of them would be muscular/skeletal.

Borgen: We never got to the mental listing, as I remember. We never got to that. Fortunately that is an area that--I don't know if I told you the story. At one point, when we were considering the guidelines or the standards for disability insurance benefits, when we had the problem of neuroses and hysteria and all that sort of stuff, we got some guys over from St. Elizabeth's and we wanted to know what they thought. Of course, we had medical advisors of all sorts but this was the hospital. These were guys that were in the business of treating mental illness. They didn't like the idea at all of our paying benefits for things of that sort and considering them practically permanent. It would interfere with the therapy.

Q: ...because they were trying to cure them?

Borgen: They were trying to cure them, and they would be put in the position of trying to cure a guy whose whole outlook and slant wants to be disabled. And they are put in the position of trying to defeat his entitlement. It presents a metaphysical, ethical, moral, dilemma. However, he did say, "By acknowledging the condition and its severity you are lending some credibility and gravity to the handling of these cases." It indicates...

Q: ...there is something seriously wrong.

Borgen: There is something wrong. This guy is hysterical and he can't move. Yes, he can't move. He simply can't until we cure the condition which brings it about, and it's not physiological or anatomical. It's not even neurological; it's just whatever. Well neurology gets into a little deep water here. So they thought that it should be included, preferably, if it could be done without paying them benefits. However, if we are going to pay benefits for physical conditions and diseases, they thought we also ought to do it for mental impairments, but they were very reluctant. We did include them and in CWB we avoided it. We didn't get involved.

Q: Here's the field office instruction handbook, a copy of the handbook. It even has the forms.

Borgen: What's the date on this?

Q: This is January '43.

Borgen: I see.

Q: So it even has the forms back here.

Borgen: Incidentally (I just noticed), the President's allocation was in terms of temporary aid.

Q: Right. I think that was...

Borgen: And when the funds ran out, that's when it ended.

Q: Here was the form that you used to...

Borgen: That's right.

Q: This was the CWB7 form.

Borgen: The title shows: Social Security Board, Bureau of Old Age and Survivors Insurance, Civilian War Benefits, US Public Health Service, Civilian Medical Care.

Q: And that was the Joint.

Borgen: That's the "Joint."

Q: And this is the physician's report.

Borgen: Civilian War Benefits. Yes, that's the way we operated. We worked very well together, considering there were a lot of borderline areas.

Q: I'm really interested in the disability program here, but this Civilian War Benefits program actually had two other parts to it besides the disability benefit. One was what was called Civilian War Assistance, which was help with relocation and repatriation of people who got stranded and stuff like that. I know you guys didn't do it...

Borgen: No. That could have been in the Bureau of Public Assistance.

Q: Then there was another part; it had to do with enemy aliens, we funded the relocation, the internment, of the Japanese in the West coast, and other things under this program. Do you know anything about that?

Borgen: No.

Q: Let me ask you a question that you probably won't know and I don't expect you to, but just by chance. One of things I've been trying to figure out is how many cases, how many claims we processed under this program. Do you remember at the end of this thing, a report or anything that said here's how many cases...

Borgen: I'm sure that we made reports and we received reports and maybe Research and Statistics compiled this data for us. I don't remember. I know at one point we reached the million dollar mark in payments and I don't remember whether that included medical care or not.

Q: I think they had a separate fund.

Borgen: I don't recall how we divided the funds. But we paid out a million bucks and it was small potatoes compared to Social Security. It simply indicated something about the value--the significance of the program.

Q: Here's the question that most interests me about this. In effect, Social Security was in the disability business briefly during the war. How much of what we did during this Civilian War Benefits program carried over to what we ended up doing in the planning for disability insurance?

Borgen: It's hard to say. For one thing you may have noticed from the schedule we had here it's essentially partial disability. In the insurance program (DIB) that had no significance.

Well what we learned was problems dealing with the attending physicians. We learned some of the problems in evaluating disabilities, recognizing a partial from a total, and that there is an appreciation of the big difference between finding of date of death and a "disability" as defined. The carry over--aside from those atmospheric and attitudinal things--was not much, except that public response turned out to be more crucial in DIB.

Q: How about working relations with other organizations involved in disability, like the VA. You talked to the VA to help do this rating schedule and you ended up talking to the VA again when we ended up doing the disability listings.

Borgen: Oh yes. There was no problem with the VA during the CWB period.

Q: So that seems to be some carryover...

Borgen: The Civilian War Benefits programs was in many ways comparable to the Veterans Administration's Division of Pensions and Compensation. But the Veterans Administration also had a disability insurance program which was operated like a life insurance with disability provisions in it. What they did there was more like what we were going to do eventually when DIB was enacted. The Veterans Administration's insurance definitions of total disability were very much like Workmen's Compensation total disability, where it wasn't a matter of a partial thing, more like DIB. For those cases, there is a lot of judicial precedent. Many of those cases-- Workmen's Compensation or disability insurance, private disability insurance policies and Veterans Administration disability insurance--those have been gone over quite a bit by federal courts, as well as the state courts, depending on what program was involved. That experience was more related to ours.

Q: After Civilian War Benefits ended in '45, it wasn't very long before we had to start planning for the freeze in '52 and so on. Did you kind of keep your hand in disability that whole time. I mean you had experience running the disability program for two years and then a few years down the road you're back in that business again.

Borgen: Well when they were planning disability we didn't know what we were going to get. The legislative period was a peculiar one. First we didn't get anything, and if I recall the steps, the next thing was Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled--public welfare. The next thing was as I recall--it's logical but it may not be accurate chronologically--the disability freeze and then...

Q: The program.

Borgen: The freeze was the camel's nose in the den, and I remember somebody later saying then the whole camel came in with Medicare.

While these steps were going on we were...I was doing some other things. I don't remember what. In the very early stages my experience here was called upon, but from other people, to develop memoranda and things of that sort. Social Security didn't get it, but Public Welfare got it on the basis of need. I know I went to Baton Rouge, Louisiana where we figured that would be a good place to study how they were working. And we saw how they were working and how they evaluated things and it was vague and general. We didn't come back with any great contribution, other than we knew the problem would be with the medical evidence. And in Public Assistance the fact that the people involved were in need of the money carried a great deal of weight.

Q: Made it easier. In fact I sometimes think that was the reason that we were able to do disability during the war, because the special emergency of the war allowed people who resisted the idea of a disability program to accept a temporary disability program. Would you agree with that?

Borgen: You mean Civilian War Benefits?

Q: Yes.

Borgen: You got to remember that during that war the morale in this country was not what it had became with Vietnam or Korea. There was no question about patriotism and whoever was involved was doing their best. So there was a lot of sympathy and recognition that these people had to be taken care of.

Q: Anything more about Civilian War Benefits?

Borgen: We had a lot of good help and other things and the way we worked the medical provisions in Civilian War Benefits was very smooth, except at one time. We had Chuck Hayden. Hayden was later Medical Director of the Massachusetts, health insurance plan. For a while he was detailed to us during the war. He was detailed to Civilian War Benefits. A big, strapping, good-looking guy, in a uniform, and in the elevator on the way up in the Equitable Building all the girls would get excited to see him. We had a staff and we were making the disability decisions. But Hayden would say "this guy is disabled; this guy isn't disabled." I had to tell him, "That's my job." I'd say, " you do that and I'll do this." He hit the ceiling. He was a big guy.

Q: So he was like a medical advisor or what was his job?

Borgen: We had a whole series of people that came and went that worked with us in the "Joint Office." They worked on the medical costs, the guys who were injured and they were also...

Q: So he was from Public Health Service? So like McKnealy and...?

Borgen: Haroldson...

Q: So he did that?

Borgen: He later testified. Chuck Hayden was called as a witness. He was okay, except that he thought the doctor should make the medical decision. Naturally, Bill Roemmich had a lot of trouble with the administrative people. To some extent he was justified. They just didn't talk the same language. The administrative people wanted production; they wanted the decisions to be more administrative. The physicians were thinking in medical terms and they wanted to do all sorts of studies which could have added to medical knowledge, I suppose. And they were at odds.

Q: You were in the middle?

Borgen: I was in the middle. Bill Roemmich had good ideas, medically. Administratively, he had some weird ideas of how the law's administered, how it's formulated, what Congress can do, should do. I pointed out to him, "Look, on the whole we're managing--we don't do everything--these guys, Bob Ball and the others, they're doing a good job, we are in business and we're doing a good job." But he couldn't understand it. On the administrative side, Bill Roemmich is a good scientist, a damn good scientist. A good scientist is often a lousy administrator. They just don't work together. You listen to him and so on and so forth, and we work it out.

Q: As you said before, in the early days of the program, in the late '30s, already people at the Social Security Board were talking about disability and wanting to add it into the program and trying to agitate for that eventually. . .

Borgen: Well it wasn't very active. It wasn't very public.

Q: But it would be almost 20 years before we really got that program and there was a lot of resistance to it from different places. You talked about some of it before--the AMA and so on.

Borgen: And the insurance companies.

Q: And the insurance companies.

Borgen: And the state workmen's compensation programs--represented in the Labor Department and by the I.A.I.A.B.E., And so forth.

Q: It almost seems to me that this little experience we had from two years of the Civilian War Benefits program was the camel's nose under the tent, or the first experience. It seems to me to be significant because it's our first experience with a disability program. Do you see it that way?

Borgen: CWB worked. It worked. We were able to work with the physicians. We had the cooperation of the attending physicians. Our problems were technical, not social or economic or anything like that in CWB.

Q: Because there were a lot of doomsayers who said disability could never work.