Manuel "Manny" Levine

Manny Levine, 4/14/64. SSA History Archives.

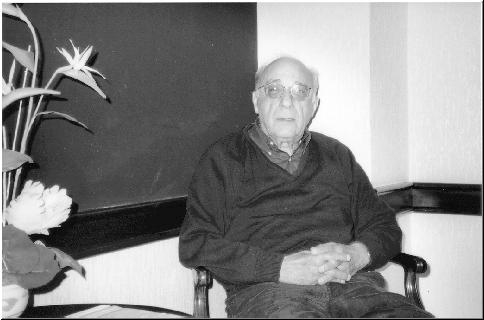

Manny Levine at his home in Baltimore, Maryland at the time of his oral history interview, March 22, 1996. SSA History Archives.

Levine Oral History Interview This is an interview in the SSA oral history series. The interviewee is Manny Levine; the interviewer is Larry DeWitt, SSA Historian. This interview took place on March 22, 1996 at Mr. Levine's home in Baltimore, Maryland. The interview was transcribed by Robert Adams and Mary Haskins of SSA's Braille Services Unit. The questions and any editorial comments are shown in italics, to distinguish them from Mr. Levine's remarks. Q: Manny, my favorite first question is how did you come to work for SSA? Levine: Well, I graduated from law school in 1940, and I clerked for a year in New Jersey--that was my home at the time. Sometime in the beginning of 1941, I realized--with my clerkship ending--I had to do something, and I wasn't ready to go into the practice of law, so I was sort of looking around. I took an exam, got interviewed by the manager of the district office in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and we talked for a while. And then sometime about May, I got a letter that there was a vacancy in Camden, New Jersey. In the meantime, I was getting married, so I thought this would be the ideal thing. I got married and got a new job, and the salary was really magnificent: $1,620 a year, which at that time, to put it in perspective, was excellent. As a clerk in a law office, I was getting $50 a month, so here I am, going from $50 a month to $30 a week. So I felt real rich at that point. And then I got married. On June 21, 1941, I took a train with my wife to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and got sworn in by Joe Tighe, who was then Regional Representative, and he gave me a ticket to Washington, D.C., to go on a 6-week training course which was run by a fellow by the name of Francis McDonald. At that time, they were real chintzy; I didn't get any per diem; all I got was the travel. And they told me I would get per diem on the last week of the course. So there, for 5 weeks, my wife and I had to live in a rooming house. I got my pay check but I got no per diem. It was an interesting time. The training course was very interesting. McDonald was an interesting character, and we learned a lot, and my legal training was appropriate for what we were doing. We had the usual stuff, how do you determine relationships and so forth. Then we made a trip to Baltimore. We went to the Candler Building, to see how they did everything. At that time claims were adjudicated at 1825 H Street, so we spent some time there. And then the last week, I got my per diem--$3.00 a day--so I felt really pretty good about that. Q: Let me ask you about the training course. There were a couple of interesting things about it. The first was that we used to bring everyone to Washington or Baltimore to give the training and years later we stopped doing that; we don't do that any more. But also part of what used to go on in that training course, especially in the early years of the program when it was a new idea, was training in the philosophy and principles of social insurance. Levine: McDonald knew very little about the technicalities of the law; he used to have the adjudicators in the Payment Center give us the technicalities: you have to prove age, you have to prove relationship; you have to do this, you have to do that. And McDonald would talk the philosophy, and we even had talks from a fellow named John Corson, who was Bureau Director. John Corson came in and gave us a speech. There was a lot of philosophy, a lot of feeling for what the Act was supposed to accomplish; it imbued you with a certain spirit of the need to help the people. It was very interesting and something that hadn't really been recognized. So when I finally left Washington, I went to Camden, New Jersey, and then I really hit it hard; I just didn't realize what I had gotten into. I ran into the worst SOB in the world, Mr. Davis, who was manager of the district office--I have never seen anyone so bad. First of all, the fact that I had gone to Harvard University and Harvard Law School was something he was going to take out on me; it was like going into the Army, and he really took it out on me; he gave me the worst jobs in the world. Q: And you were a claims rep? Levine: No, no, I was a field rep, which was terrible. If times were different, I probably would have quit. But he just degraded me, demeaned me --it was terrible. When I walked into his office, the first question he asked me was, "Do you have a car?" And I said, "No, I don't have a car." "Why don't you have a car?" And I said, "Well, they didn't tell me I need a car for this job." A field rep wasn't doing very much then. So the first thing he gets on the phone and calls Joe Tighe. "Why did you send me this guy," --right in front of me--"He doesn't have a car. All he has to do is go out and get C-numbers"--you know what C-numbers are. The response from Joe Tighe was, "well, we can't require an individual to have a car; we'll just have to work it out." "Well, I don't know if he's any good for this job," was Davis' reply. Fortunately, my wife had a dowry of $800 she had in the bank, so I took $200 and bought myself a car, because otherwise I couldn't do the work. And the main job was C-letters. C-letters were letters that came over from the Internal Revenue office where names were put on Social Security checks and the Social Security numbers were missing. And here I was, 7 years of college, running around just looking for people to get their numbers. There weren't any claims to be taken--well every once in a while, you would have a claim. Q: Something puzzles me. You were a field rep, so that meant you had to have a car and go out. But were there people at the office--claims reps were there? Levine: Oh, yeah, well they didn't call them claims reps, they called them claims assistants. People were coming in and they were taking claims. Q: But they needed someone to go out and do this? Levine: That was the only thing we could do. The purpose of the job was to go out and help individuals file a claim. But people weren't filing claims. Every once in a while, you would get a claim because a person was disabled and couldn't get into the office. But if you had to go file a claim from, say, Camden, New Jersey to some town a good 25 miles away, well, you would take a bunch of C-letters to get the Social Security numbers. You would approach the employer and ask, "Where's Joe Doe?" "I don't know what you're talking about" was often the response. They didn't have any names; you had to get numbers. Or a C-letter would have a wrong number; "get the correct number." "Well, that's the number he gave me." It was degrading. And then, of course, the war started and there were a lot more openings in Social Security. And another thing is, you were promised a raise after a year, as a field assistant; then you began to be a senior field assistant. And you went from $1,620 to $1,800, but you had to pass an exam--it wasn't automatic. And after you passed the exam, it would take 2 months before they put the papers through. So they weren't giving you anything at that time. Q: How large was this office--roughly how many people were working there? Levine: In the Camden office there was only 1 field rep, and 1 manager--they called it a Class 2 office at that time. And it had maybe 1 or 2 people on claims, and about 2 or 3 people behind the counter. It wasn't very big, but it had the classification of a Class 2 office. Some of the other work would be--at that time they used to have what they called, "1001's"--you used to go to the employer to get the most recent earnings since the computation of the average monthly PIA went to the time the guy filed. So there was a period of about 8 or 9 months where it was not on the record. So you had to go up to the employer--the last employer--and get those records filled out. And you sent it to the employer --sometimes, he would answer; sometimes, he wouldn't answer. Well, if he didn't answer, after a reasonable length of time, then I had to go up and get the 1001 and fill it out. I stayed in Camden from August 1941 until about October 1942. I remember taking the exam in Camden, so I had been there for about a year, and then I went to Trenton. By this time, the war had started, so there were a lot of openings, and I was promoted--no, I wasn't promoted, just shifted as a Field Assistant from Camden to Trenton. And that was even worse. The manager there had ben gassed in World War I; he just didn't know what it was about. I don't think he knew that there was a Social Security Act. He was a politician, he was part of the Haig Machine in new Jersey; just one of many politicians; they had to give him a job, so they made him manager of the Trenton office. And I'd sit there amazed, talking to him about some of the problems, and he didn't know what I was talking about. Eventually, they got rid of him. He didn't know what a tax return was; or what a claim was; he'd just sit there and mumble all day, and I was working with this guy. I took the bar exam in New Jersey and I passed. I wanted to get back to Newark, New Jersey. I thought maybe I would leave the place and get into the practice of law, so I made up a big cock-and-bull story about how I wanted to get back to Newark, and my parents didn't feel well and blah, blah, so they said, "Okay, we have an opening in Perth Amboy, New Jersey." Now I became an Administrative Aid and was up to $2,000 a year. Q: An Administrative Aid, what is that? Levine: It was just a title. I was just a glorified field rep; but it was an increase in wages and I guess the Field Assistant job went up to CAF-4 (clerical-administrative fiscal); now it's GS. They wanted to give me a CAF-5, but there was no Field Assistant job at CAF-5, so they called me an Administrative Aid. So I went up to Perth Amboy and another manager. See, in the beginning, they selected their managers on the theory that if you sold insurance, then you were going to be a manager, even though you had only been in debit insurance--you went up and down the stairs and collected 10 or 15 cents a week. So all of these guys were insurance agents; they had no concept of social insurance. And the new group that was coming in--guys like me with a college background who understood something about the program--were foreign to these guys. Davis was an insurance man, this other character was an insurance man; Fitzgerald in Perth Amboy was an insurance man, they had no concept of social insurance. So it wasn't very interesting working with these people. And Fitzgerald used to live in Atlantic City, so he wanted to transfer to Atlantic City. So we were going to get a new manager. And lo and behold, we got a new manager who understood what was going on, Arthur Hess; he was my first manager who understood the program. So he came into Perth Amboy and I found it really enjoyable working with him. We developed a certain relationship which lasted for many, many years. Every once in a while, you get an intricate relationship problem and he could understand what I was talking about. And the work was about the same - during the war time, there weren't many claims to be filed. But I remember in 1943, I got a letter from a friend of mine who was an attorney--we went to high school together and he went to Boston University, while I went to Harvard. And he wrote me from Baltimore, and said he's got a job in the General Counsel's office. So he says, "Why don't you come down and see; they need people." So, I went for my leave that year--1943--and I came down to Baltimore, and I went to see the Assistant General Counsel who was attached to OASI (old-age and survivors insurance) and talked to him. He said, "You know, I'd gladly take you on; we're losing people." But I wasn't on a particular list, and they couldn't take me. But he said, "I'll send you down to see Ewell T. Bartlett, who was in claims policy work." So I went down to see Ewell T. Bartlett, and his assistant, Mercia Leton. Ewell Bartlett was a lawyer, he was a pretty nice guy; as a matter of fact, he used to work in the General Counsel's office. So we talked about some of the problems in the district office and I told him what the problems were. I guess he was fairly impressed by what I said, and they made me an offer to come to Baltimore. Q: In Claims Policy? Levine: In Claims Policy. And now, I'm at the grade of CAF-7, earning $2,600 a year; the war is on, it's a 6-day week doing time-and-a-half on Saturday. So I'm earning about $3,200 a year now. And my wife and I came down, and they put me on one subject on which I stayed for a year and a half: equitable entitlement. Q: I know the concept but I've forgotten what it is. Levine: Equitable entitlement is a lump sum death benefit, payable after the relatives have gone. Who was equitably entitled? That concept had all kinds of ramifications: gravestones, digging up graves; funerals; and with the Jews, when the gravestone isn't put on for a year, how do you treat the lump sum--do you give it all out or do you wait? It was very complicated. And that was the only thing I worked on for a year-and-a-half --equitable entitlement. I got a little sick of equitable entitlement; it would have you up the wall. I got a little sick of it, and in the meantime, a friend of mind worked as an attorney at OPA--the Office of Price Administration, during the war. So he said, "What are you doing over there? Why don't you come to Washington, and work in OPA--we'll give you a grade 11 right away, no problem." So he said, "Come on down, and talk to us." I went down and talked to a guy and he said "You got a grade 11; when do you want to start?" Well, I'm grade 7 at Social Security, so I was on cloud nine. I didn't know what to do, so I went back and spoke to Mercia Leton, and said, "I got an offer for a job at OPA at grade 11." "Well, you know, there's a restriction on transfer," she said. All of a sudden, I became the most important guy in the world. "We won't let you transfer, because under war conditions, you have to get permission, and we think we're losing people we need." Well, I guess what they did was they finally decided they'd do something for me, so they gave me a grade--it broke their hearts--they gave me a grade CAF-8, and I was going from $2,600 to $2,900, and I still wasn't satisfied. Something happened--there was another opening for me--I could go back to OPA. I said, "I'm going to try it again." My friend was still there. This was in April, 1945. The war was coming to an end--but I didn't know the war was coming to an end. So this time I went up to Ewell Bartlett and I said, "I got an offer to go to OPA." And he said, "Well, I understand what you want to do." He understood me; Mercia Leton didn't. I said, "I've had 3 years of the best law school in this country; I want to get back into law." He said, "I understand. I'll tell you what I'll do, I'll see if I can get you a job in the General Counsel's office. That's the best we can do for you; I'm not going to release you for OPA." And he said, "From your point of view, I think a career is better for you up there." I wasn't too anxious to do that, but it was there, it was a job, it was legal work, and it was a grade CAF-9--I'm really going up the ladder. So I went up to the Office of the General Counsel, and a fellow by the name of Lou Ayres was in the Office of the General Counsel. And he had seen me around, and he knew who I was and he said, "yeah, sure." (You have to know Lou Ayres, as long as you walked in, he took you.) And so on May 1, 1945, I went to the General Counsel's Office and stayed there until March 8, 1956. And I guess my greatest progress in government was in those 11 years. I liked the work there, it was very good, and I was a grade 9 and guys were coming back from the war now, and a fellow by the name of Harold Packer became the Assistant General Counsel. And I guess he took a shine to me for some reason--probably because I was a hard worker. And there was an opening for a supervisor--I never had a supervisory job, and I'm nervous. And he said, "Manny, I want you to take that job." And I was really scared--I didn't want the job. First of all, the guys I was working with were guys I had known over the years, and they were my peers, and all of a sudden I'm going to supervise these guys, and I didn't like that. And he said, "You'll never get ahead if you don't take this job." And so I said, "Okay, I'll take it." Well, that was really something. People in Claims Policy couldn't imagine how I did it. Here was this guy--a grade 7 or 8--now I'm a grade 11 and I'm giving orders. They thought I was the smartest guy in the world--how could this guy do it? Harold was a funny guy to work for, but he was a good guy to work for, he recognized if you did a good job, he recognized you for it. We're probably talking about January 1947 and sometime just before the election of 1948, he gave me another raise; I got a grade 12 now. And I'm not only supervising lawyers, I'm supervising supervisors of the lawyers, so I'm really moving up the line. In 1948--I don't know if you read about this--Truman said when he accepted the nomination he was going to have a special session of Congress, and was going to get a lot of legislation passed. He was trying to put the "do-nothing 80th Congress" on record. And so I had to draft legislation--I had never drafted legislation. And so Harold was being called down to the Department now--it wasn't HEW, it was the Federal Security Agency. And he said, "Come with me, and get involved in legislation." And that was a real revelation to me. I helped work on the bill--the final bill that they developed--to submit to the 80th Congress when Truman called them back to the special session after the conventions. There's something about my background--when I went to college I majored in mathematics. Mathematics was specific--1 plus 1 is 2; it isn't 3, it isn't 4. It isn't like writing an essay on economics where you say, on the one hand do this, one the other hand do something else. So I developed a certain talent for proficiency, clearness, conciseness, etc. And that's very, very helpful in drafting legislation. So I worked with Harold on that. And then, of course. . . Q: What was in that bill? What was being proposed, do you recall? Levine: I haven't the slightest idea. Everything except the kitchen sink. Truman knew it wasn't going to be enacted, but he wanted to put the pressure on them. He said, "Look, I submitted a bill to increase coverage and all that kind of stuff," and he knew nothing was going to happen. Q: Did it have anything to do with health insurance at all? He had proposed earlier a national health insurance plan. Levine: I don't think he did anything on health insurance, not that I recall. I don't remember the details of the bill. But after Truman was elected in 1948, then the gates were open. And we spent the end of 1948 and all of 1949 working on the legislation. The House didn't pass the bill until the end of 1949. Then it went over to the Senate and the Senate worked on it until 1950, and the amendments were finally enacted in August 1950. Q: So it became the 1950 Amendments. Levine: Yes. One of the interesting things there was the disability program. And it had its start there. I was working on everything but coverage--coverage and wages. Harold was a coverage and wage man, and I was everything but that. So you were thinking about disability benefits, entitlement issues, and the technical features. And during that process, I developed techniques and talent in drafting legislation. I loved it--it was a real challenge. The House enacted the disability program, I believe. But before the Senate acted, we started to work on disability. And Harold gave me the job of finding out, "What do these words mean?" Substantial gainful activity--what is substantial gainful activity? And most of it came from the Veterans Administration. Just as an aside, it was supposed to be, "substantially gainful activity" because it was modifying the word "gainful." I said, "you need an adverb in front of it." But for some reason, it was left out. The Veterans Administration was substantially gainful activity, that was one concept. Social Security was "substantial, gainful activity." So we wrestled with that for a while. I remember giving a number of lectures--talks to people in Claims Policy who were going to administer this and what the right word was. Meantime, Art Hess had come down to Baltimore, and he had a little task force on this. And so they were involved in developing specifications and policy on this. And I wrote a number of papers on that, which did see the light of day--people did read them. Then when the bill came to the Senate, the disability provision was knocked out. They left in disability for the welfare program; they knocked out title II. In trying to develop amendments to the bill, I remember saying to the draftsmen in Washington, "Hey, substantial should be substantially." So I said "in line 46, add -ly." And it came before the Senate Finance Committee and Senator Byrd--he did not want that -ly in there--he wanted it to be "substantial activity" not "substantially gainful activity." That's how law is made. I think it changed the concept somewhat over the years. The disability program didn't pass. And that took us to 1952. (And they got a little bit of agriculture in there; a little bit of domestic service.) Then came 1952. The Democrats wanted to do something for the people; so they had a series of amendments. And I worked on those. I worked on every series of amendments thereafter--1950, 1952, 1954, 1956, 1958, 1960, 1962, 1964, or 1965. And each time I was involved in the drafting phase. The 1950 Amendments didn't have anything on disability. In 1952, they put in a disability provision which was terminated before it became effective. Q: That was a disability freeze, wasn't it? Levine: There was a freeze provision that ended on June 30, 1953 and went into effect July 1. And Congress was supposed to take action on that, which they didn't, so it went out of business. Of course, in the meantime, the Republicans got in, Eisenhower and Ovetta Culp Hobby, the first Secretary. Then they changed it to HEW (Health, Education and Welfare). Q: Could I ask you about a couple of people who left when the Eisenhower Administration came in, and I just wondered if you had any dealings with them? One was Wilbur Cohen--he stayed on for a while. And Altmeyer. Levine: Cohen stayed on until about 1956. You see, Altmeyer was Commissioner for Social Security. First, there was the Social Security Board, and Truman eliminated that Board and made Altmeyer the Commissioner. And when the Eisenhower Administration came in, they wanted to get rid of Altmeyer and they couldn't do it, so they changed the title of the job so the job terminated. And Altmeyer needed about 8 or 9 months until retirement, and they offered him some job as a consultant for regulations. He wasn't that kind of a guy; he said, "I've worked on this program for 20 years, and I don't have to stop and look in the regulations." And so, he just left, even though he had only about 8 or 9 months before retirement. And so, Bill Mitchell took over. And Wilbur Cohen was then his assistant. And Wilbur hung on until 1956, I believe, and then he resigned and went to the University of Michigan to teach. I didn't have much to do with Wilbur Cohen at that time. See, although I was in legislation through the General Counsel's Office, the responsibility for legislation for HEW and SSA was in Washington. And I was sort of the helper to the guys who were doing it in Washington because I had the technical knowledge on Social Security and they had to rely on me. But insofar as dealing with Wilbur Cohen was concerned-- dealing with the committees and all that--I never got involved with that, although every once in a while, I would go to the hearings. But I got to know Wilbur Cohen a little, and he got to know me because, in the course of regular activity, he might ask, "Who worked on this?" So my name came into the mix. I got to know him; I saw him, he recognized me, and we talked for a few minutes. I got to know him very well subsequently. Up until 1956, I didn't have very much to do with him. Q: Well, you can tell me more about him later. I'm interested in these stories and his personality --I mean, he's a big figure in all this history. Also, when Altmeyer left, was that a traumatic event for the agency? I mean, was it a big change? What was it like? Levine: It was a different atmosphere. Hobby was in there--Ovetta Culp Hobby--I think she more or less bypassed Altmeyer from the point of view of old-age and survivors insurance. I think she dealt primarily with Bob Ball, and then she got this guy, Christgau in there. You didn't feel the effects of Altmeyer--maybe the top guys did like Cohen and Ball, but the guys like us, living and working in the trenches, we felt it was a tragic thing to get rid of that guy. Like Roosevelt dying: "Who the hell's going to take over this country?" Altmeyer's gone. It was the Social Security Act going down the drain. He went and that was it. Someone took his place, and life went on. In 1954, finally the Republicans decided that they had to do something, so that's when they first came up with the freeze, and this time, it went through. And a lot of other things happened; they increased the wage base, eliminated some of the problems in agricultural employment, increased coverage, like State and local. I forgot some of the other things. And I got involved in that very heavily. One of the big problems was that if you were going to change things, you wanted to make certain no one gets hurt. If they knew that some guy in Idaho had a problem, you had to take care of the guy in Idaho. And so they had about 16 or 17 recomputations and then all these new things coming in. There was a lot of activity in trying to get the technical features right. And I was still in the General Counsel's office, and I really enjoyed it. 1955 was the next step. Now the Republicans are out in Congress, Johnson and the Democrats are in, and so they started with monthly disability benefits. And the Administration was fighting them tooth and nail. And the guys in Baltimore were insubordinate. In 1955, the House passed the bill. But in 1956, Wilbur Cohen was out, and he's working for the AFL-CIO and they were trying to get the disability program in, and Ball is dealing with these guys on these under-handed midnight rides to Washington. And I was in the midst of all that. As a matter of fact, they were going to fire Ball for insubordination. Q: He was lobbying for the bill? Levine: Marion Folsom, who was Secretary of the Department, was opposing the bill. Ball was giving the Democrats technical advice--he wasn't doing the right thing. What happened to me at that point: Now, I'd been working in the General Counsel's office from 1945 to 1956, and I'm getting a little unhappy. And I'll tell you why I was getting unhappy. Although I was getting raises--I'd now become a grade 13, and I'd become a supervisor of the supervisors of the supervisor, then I got stuck at that point. Meantime, the Claims Policy division with whom I'm working, and with whom I'm advising on the legal aspects of the program, are moving up the line because the program is expanding, it's more complicated and all of a sudden, the guys whom I talked to, day in and day out, they're grade 14, and I'm a grade 13. So I didn't feel too happy about that. So I went up to Harold Packer and I said, "Look Harold, does the name Gus Myers mean anything to you--he was in charge of certain aspects of the program--he's a grade 14, this other guy's a grade 14, I'm a grade 13, and I'm talking to these guys, they're relying on me, won't you talk to someone in civil service or personnel and see if our jobs can't be reclassified?" And here's a guy who's friendly with me very much and he really got a lot of work out of me; so he said, "If you don't like it around here, leave." So I said, "Fine." So I went over to see Bob Ball. And I said, "Bob, I'm having problems with Harold Packer." (Meantime, I've developed a certain relationship with these guys like Bob Ball, Alvin David, because they saw I had this talent for the legislation.) And Ball said, "You know, we've got a project going on here, we've got a project called the simplification project. "You've never heard of that did you?" Simplify the Social Security Act. And he said, "We can't give you a raise." And I said, "I don't care, I don't want a raise; I'm just trying to get away from that guy for what he did to me." And he said, "Okay, you can come over to the simplification project." Q: This would be in policy then. Levine: No, it would be in Program Analysis. By this time, Jack Futterman--you remember Jack--was then an assistant to Alvin David. And Jack Futterman was going to be the major supervisor of the simplification program, and I was going to be his assistant to doing it. Did you ever work for Jack Futterman? Q: No, but I know him. Levine: He's one of the smartest guys I've ever run up against, but he's a very difficult guy to work for. And here I was leaving the General Counsel's office where what I said was authority: Levine says the law says this. This didn't work for Jack Futterman--"Whatever you do isn't worth anything because I didn't do it." I'd give him a letter or a memorandum, which was pretty good, he'd tear it up to pieces. It had to be Jack Futterman's work to go out. And the idea is that I was supposed to form groups, groups of people, and we'd take a program area and try to simplify it. And the first thing we did was--equitable entitlement! "We're going to simplify the lump sum." It was at that point that I had to develop groups and I needed someone to develop groups. I didn't know enough about the administrative aspects of this because I had never dealt with administration. So I got a hold of a guy whom I thought would do a good job--Tom Hart. Tom Hart came to work for me. He had just come down from San Bernardino and he wasn't doing very much. Tom and I hit it off very well, we had a lot of fun together. We sat in one room. But we weren't getting anywhere-- you get these groups and they weren't interested in this. You had a fellow whom you would tell, "work on equitable entitlement." But his supervisor might want him to do something else, he didn't want him to monkey around with this. So Tom and I would write these long reports on how you simplify the program and we would submit them to Alvin David and Jack Futterman. And it would stay there; you never found it; you didn't know where it was; you'd ask him about it and it was stuck down there. But this was our work and it kept us busy. Even though I was in that program, they still didn't leave me alone on legislation, so that when legislation came up in 1956, 1958, and 1960, I was doing the drafting of the legislation and, at the same time, doing this other program. But we were getting absolutely nowhere. We wrote a lot of good memoranda, and that continued for a while. The 1956 legislation finally passed; in 1958, they had more things. In 1960 they wanted to simplify the computations. So Tom and I worked out a plan and we came up with something real good. But it fell into the hands of people in Program Analysis who were jealous; computation was their field; what are you two guys doing here? And it was just lost there. And in 1960, they reactivated it. For some reason or other--I don't know how it is--it got to Bob Ball. So he says, "Where has this been all the time?" And I said, "Well, you know, we gave it to the people in 1958 and they weren't interested in it." "Well, we're going to go with this," was his response. And that revised the whole computation process. Of course, it's changed since then, but it revised the whole computation process and made it much easier too. And if you ask me the details, I've forgotten them. All I know is that we did something about it and it was a big change. Q: And it became part of the 1960 amendments? Levine: It became part of the 1960 Amendments. The guys, the draftsmen, were in the Legislative Counsel's office of the House of Representatives--they were the ones who were responsible; but again they didn't have the technicalities, so they relied on us. And they had to sell it to the Committee. But someone had to sell it to these draftsmen--to the Legislative Counsel, and I was given the mission of selling it to these guys. No one else could really--it was really technical. Tom and I would go to Washington and we'd drive there 3 or 4 times a week. They might have been working on 15 different things, but they figured that computation and recomputation was going to come up some time during that day. So we might get there about 10 o'clock in the morning and stay until 6 o'clock in the evening. And finally, I remember the very last day, they had a deadline of about 8 o'clock at night and I was in Baltimore--by now we've moved over to the building, we've left Baltimore, this was the Woodlawn building. I remember getting on the phone and talking to these guys. We finally sold them the concept, they bought it and it went into the law. Those were very trying days, but very exciting days. When we were in the Equitable Building, there was no such thing as grabbing a car and going to Washington. What you did was, you ran down to Camden Station (where the Orioles are now). There was a train that went to Washington, and you go up to Penn Station, and you do your work, whatever it was, and you came back by train. There were a number of times you would get in there and you would miss the last train, and we would take the first train in the morning and get back to Baltimore at 5 or 6 o'clock in the morning. We'd be sitting around talking, because the draftsman had an assignment to get something in at a certain time, and they kept going all night, they didn't care. And so we stayed there with them. It wasn't much of a problem; you know, you were youthful then. But I would go to work right away, and I would come in at about 5 or 6 o'clock in the morning, take a cab from Pennsylvania Station or Camden Station home, wash myself up, have breakfast, and then go back and go to work. Finally, in 1960, we came over to Woodlawn. Q: Tell me, before you go on with that, tell me a little about the Equitable Building and about working downtown. Levine: Well, you know, the Equitable Building was an old building. You have to understand that we weren't very large, you could get the whole operation into about 4 or 5 floors--the 6th, 7th, and 8th floors. On the 9th floor were the executive offices--Oscar Pogge was there, and Futterman when he was the assistant, and a few other guys--Reed Carpenter and a few other guys. Then they had the guys who did the financing and the budget and all that, and the next floor, you'd have the General Counsel's office and the training office and, on the floor below that was somebody else. And I remember we were on the 6th floor--Program Analysis, and somewhere along the line, Field Operations and Claims Policy were there. So what was the Bureau of Retirement and Survivors Insurance had half a floor, the other half was another group. At lunchtime you'd run out to eat or something. You'd eat at your desk or at the coffee shop downstairs, or go to some fancy place on Fayette Street. Things changed when we got into Woodlawn and it had its own cafeteria. But the Equitable Building was a great place to work. It was a pretty seedy building, the guy operated the elevator back and forth. But I don't have any other particular impressions of the place. It was nice getting into Woodlawn. It was out in the country now, parking was pretty good, you could get a parking space, if you drive your car, you didn't have to take transportation. In 1959, were the very first elements of health insurance. It was called the Forand bill. It was not very well drafted, it didn't really take care of the problems and all the issues, but it was there and it got a lot of play. And there was a fellow by the name of Irv Wolkstein. And he became the fountain of all knowledge as far as health insurance was concerned. He studied it, and so he came to me one day and said, "Truthfully, you're not doing anything are you?" This is the simplification project. And he said, "I know what you're doing. Why don't you get involved in health insurance?" So I said, "Okay." So I started reading the Forand Bill and he said, "Let's see if we can fix up a better bill than that." And he developed a bill--he developed ideas for a bill--and I put in the language. This was not part of any assignment or anything; this was just something on the side--it was almost like an avocation. And we'd talk about it and I'd give him a piece of paper. I wasn't doing anything. Tom was playing around and was looking to get out of there; he said there was no future in it and eventually he did--he went to McKenna in Field Operations. And I worked together with Irv on this, and we transferred and kept doing this and we went to Woodlawn. And all of a sudden one day, we got a call from a fellow by the name of Sidney Specter. Sidney Specter was the staff man for the Aging Committee of the Senate. And it was chaired by a Senator Ferguson of Michigan. Senator Ferguson wanted to introduce a bill on health insurance and Specter didn't know beans about it--he didn't know what to do. Somehow or other, he got a hold of Irv Wolkstein and said, "Why don't you come down here and draft us a bill?" And Irv grabbed it; he wasn't going to let that one go. And so he said, "well, you know I've got to get permission from Ferguson," and Specter didn't have any problem calling up Ball. And he said, "Let's go and draft a bill." So we grabbed a car, and drove over to the Senate, and he saw Specter, and said, "Here's a room, and here's a desk, and they're a few girls over there, they'll do the typing." Now, you recognize that we've been talking of doing this, and we drafted the first health-insurance bill; it had never been done before; the only other thing they had before was the Forand Bill. And I remember it was getting late, the girls had left, we had to have the thing typed, so I called up my secretary, who was probably one of the most devoted secretaries in the city of Baltimore--her name is Dorothy. And I said, "Dorothy, get hold of a car, and come down here." This was about 8 o'clock at night. She grabbed a car. She was very devoted, (I could have asked her to walk off the roof, and she would have walked off), and she came down, and she typed the bill. And that's the way it went. We typed the bill, it had a lot of loopholes in it, but we typed the bill. And that was a forerunner of the first health-insurance bill. Specter got the bill and introduced it. But the Committee on Aging was not going to handle that bill; Ways and Means was going to handle it. In the 1960 Amendments, that bill saw the light of day in the sense that it was looked at. And the draftsmen had to develop a bill for one of the congressmen; and they used that bill as a framework for doing it. It never saw the light of day because all they passed was the first health-insurance bill for welfare in 1960. But Irv and I felt good about it. And they said, "We're using that bill; we're making our judgments based upon that bill using it." The concepts were there; of course, they changed a great deal. Then Kennedy was elected in 1960, and Ribicoff was going to be Secretary of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Wilbur Cohen, who had been at the University of Michigan, came back and was going to be Assistant Secretary for Legislation. And Wilbur Cohen wanted to have a bill for health insurance--like two days after inauguration. So we were going to count on that. And the day of the inauguration--as you may remember, it was snowing, the government was not working--Wolkstein and myself and a few others, we worked that day. In fact, they brought in a television set, and we were able to see the inauguration on television. Q: While you were drafting the bill? Levine: While we were drafting the bill. And you know, it was a funny thing. You draft the bill, you get it all drafted, and you send it over to Washington. And as soon as that bill was drafted, they were revising it. While the bill was being typed, it was being revised--draft after draft after draft--and decisions were being made with it, and Cohen was on top of it all, he was the one who was making the decisions all the time. Ball was there, Alvin David was there--Wolkstein. And the decisions were coming down, and they were talking to the senators, and all that kind of stuff. In 1960, after the nominations, there was a special session of Congress. Lyndon Johnson was now nominated for Vice President--he was the Majority Leader--they wanted to get something in for the election. And then Wilbur Cohen--Wilbur Cohen was still at the University of Michigan (because Kennedy hadn't been elected at that time)-- and he had been given a consultant job with the AFL-CIO to do something, to get something for Kennedy through Congress. So Wilbur Cohen got a hold of Wolkstein who said "We couldn't do that." In 1960, Eisenhower was in office and Wilbur Cohen needed help in a hurry. And I remember going up into those hotel rooms with him--Irv and I going up into one of those hotel rooms, doing it on the sly, no one knew we were going to do it--we went to see Wilbur and we went over the whole legislation, told him what we had done and all that. Here it is. Nixon is running for President, and he's saying these things that the Republican Party wants him to say, and Kennedy is running against him and this is what Kennedy wants to say. Wilbur Cohen is trying to help Kennedy; and here are these civil servants helping Wilbur Cohen. So we talk about treason--that was it. Well, you know what's happened: finally they got the bill; the bill never left committee but they made a record of it for the election. Then in 1962, they had another bill come up; now Johnson is in the chair. I remember going to the Senate session. Johnson was sitting up there in the chair, because they had a bill, and it looked like it was going to be a close vote, and he might have to cast the deciding vote, but he didn't; it never passed. Going back to the disability program in 1956. I do recall, the Administration--Folsom and Eisenhower--were opposed to monthly benefits for disability. And it came up; it passed the House, and it came up to the Senate, and it was close. And just before the voting, Nixon came up--the Vice-President generally is in the chair and Nixon was there because they knew it might be a tie vote. It passed by 1 or 2 votes. And the most surprising vote in the world was Senator Joseph McCarthy voting for the bill. The story goes around that there was this woman who said she was going to get Joseph McCarthy's vote; and no one believed her. And there was an indication that--you know, Joseph McCarthy was quite a sex hound--and there was an indication that she had really developed a relationship, and as a payment for a sexual favor, he voted for the bill. I don't know if anyone believed her, but she was that kind of a gal. She was part of the group of the liberals who wanted to get this thing passed, and I guess she would have done anything to get it passed. No one understood why Joseph McCarthy voted for it. I mean, he was a good Republican. And no one understood why Joseph McCarthy voted for that bill. It was really something. Anyhow, coming back to health insurance, nothing happened in 1963, and, of course, the election in 1964 came. And as soon as Johnson won, it was obvious that they were going to get health insurance in 1965. Now in 1963, that simplification program--there were more sarcastic remarks made to me about simplification: "Ho, here comes that great simplifier; what have you been doing today?" And the program was getting more complicated, and I'm simplifying it. And it became a little bit embarrassing for a while, so I was looking for some way to get out. And I went to see Art Hess, and I told him my problem. It turned out that in the Policy Branch there was a fellow by the name of Wayne Tucker--you probably happened to come across that name; he was in charge of it-- and he was going to go to Princeton for a year on one of those fellowships they give you for a year, and Hess wanted somebody in there. I knew Art from way back, and I guess he gave me a break, and he said, "Do you want to take it?" Not only that, he said, "This will give you a lot of experience, and this is the Policy Branch for disability; this will give you a lot of experience if health insurance ever comes in; make sure you have all that experience and you'll be able to transfer that experience to health insurance policy." So I took that job, and it was, again an interesting one. I was away from the program, I got involved in administration, I had a bunch of people that were working for me, and apparently I did a fairly satisfactory job. And when Tucker came back, he was to take the job back and somehow or other, Art worked it out so that Tucker got another job and I stayed in the Disability Policy Branch. And then in 1965, health insurance came in. And they took me away from disability and I went into the drafting of the health-insurance bill and got involved in the Part A and Part B kind of stuff. Q: Now, how much of what you guys had done before in your original drafting of health insurance was used? Was some part of that in the final legislation or did you have to start over again? Levine: When we were doing it, we didn't have an A and a B; we had one. And I don't even know if doctors were involved. They did have some of the doctors--doctors that were associated with the hospital like radiologists, anesthesiologists, physiatrists, pathologists--that was part of the hospital benefit. Subsequently, they took them out because the groups didn't like being part of hospital insurance--they used to call them the RAPP services, radiologists, anesthesiologists, physiatrists, pathologists. And then, something happened. The hospital insurance portion was going through--that was the only thing that was going through. The doctors were out in the cold; and someone said, "Oh, we've got to put the doctors in." They were saying all these things to cause difficulty and to make it so complicated that they wouldn't pass the bill. Well, Wilbur Mills talks to them, and he says, "Well, if you want A and if you want B, we'll put it together. If you want the hospitals and you want the doctors, we'll put it together and make it A and B." And that's the way it happened--they just put it on top of the other, to get rid of the opposition. So there was an A and a B, and a certain amount of coordination. In the beginning, the coordination wasn't too good--there were a lot of loopholes, which were subsequently corrected in the 1968 Amendments. As soon as the 1965 Amendments were going to go through, Art Hess called me to his office and said, "Okay, I'm supposed to send you down to the task force on health insurance as the head of policy." And I said, "Art, I'm not going. I want to stay in the disability program," and he didn't believe it. And I said, "Art, I like the program; I'm enjoying it, it's a lot of fun." And he said, "you don't want to go over?" and I said, "I like this program." I don't know whether it was a good choice or not--to stay in or whether going into health insurance was the wise thing to do. But I didn't want to take a chance; it was a new program, I didn't know what I was going to get into. Disability was pretty comfortable; I knew what was going on. So I stayed in the disability program in 1965 when they formed that task force on health insurance. And every once in a while, they would say, "Why didn't you go over there?" I'd hear all these stories about what was going on and all the problems and the issues that were involved, and I stayed with disability. So the 1965 legislation came in, and they started with the program, and now they had to work out contracts with the insurance carriers, the insurance companies--someone had to draw up the contracts. And the fellow in the General Counsel's office who was giving legal advice to Ball and Hess and all that, didn't have the time for the contracts. So they took me away from disability and I drafted the contracts with the insurance carriers for Part B--with the insurance companies for Part A, with the Blue Cross-Blue Shield. So I had a lot of meetings with the Blue Cross Association, and it was interesting again, drafting contracts, and I got to know a lot of people and I saw a lot of people I wouldn't have seen otherwise. And that's when I got to know Tom Tierney and the guys from the Blue Cross-Blue Shield in Chicago. We finally drafted the contracts and they went through, and everything was fine. But I still remained in disability. Then in 1966, there was an opening in the General Counsel's office for legislation in Washington. And the fellow who was in charge said, "Do you want that job?" And I just didn't want to leave--I guess now it was BDI, Bureau of Disability Insurance. And I said, "I'll never live with myself if I don't take that job, because I've always wanted to be part of legislation." And here was an opportunity to do it 40 hours a week. Q: And not in a hotel room. Levine: And now, I'm going to be telling these guys in Baltimore what to do; I'm in charge of the legislation in Washington; we're responsible for getting it to the Hill, I'm going to tell you guys what to do." So in 1966, I broke away from BDI and Social Security, and went back to Washington. And that was a mistake; it's okay to draft legislation once every 2 years, but on a steady diet, it was just no good. I just didn't feel right, it got a little bit boring. And at that point, I went over in 1966, and they started the 1968 Amendments, but they started in 1967. And that's when I got to know Wilbur Cohen. Now Cohen was Undersecretary; Johnson had put him in as Undersecretary. I could walk into his office; I didn't have to make any appointment. Wilbur would come into my office, and we'd sit around and talk about things. And he had all kinds of ideas--doing this and doing that. I'll never forget the one time--a bill was all ready to go and they wanted to bring it over to give it to the Vice President and the Speaker of the House and all that, and Wilbur Mills and such--so Cohen said, "Well, how are you going to do that?" It was a rainy day and all that. And he said, "How are you going to get down there?" And I said, "well, I'm going to go down there." And he said, "You go down and take my car." So there I am with a chauffeur, driving around Washington in Wilbur Cohen's car. And that's when I really got to know him; it was really interesting. And then of course, when he became Secretary of HEW, I was still there. Because I didn't leave until 1969. So Wilbur Cohen became the Secretary of HEW, and there was the same relationship. I could just walk up to his office secretary and say, "I'm going to see Mr. Cohen." Wilbur was the kind of guy that nothing laid around--he did it and he wanted to see it. And we'd talk about it. And we got the 1968 Amendments passed, and I did a lot of work on it. That's when I was the man who was the contact with the Ways and Means Committee people in the Legislative Council's office. And all the stuff to Baltimore would come through me and I would go through them. Then when it came to signing the 1968 Amendments, my supervisor said, "Do you want to go down to the White House, and watch Johnson sign it?" And I said, "Not with this Vietnam thing going on, I'm not going to watch this guy." Things were really bad then, and I didn't want to see this guy. So my one opportunity to go to the White House and get a pen, and get my picture taken with Johnson, I didn't feel that I could do that. That takes me through 1968 and into 1969, and now Nixon gets in. Cohen isn't there; it's a new group. They don't know me, I don't know them. I'm sitting in a corner with nothing to worry about. But there was one event that was really interesting. After Cohen left, he was engaged by Governor Rockefeller of New York to work out a welfare bill. Rockefeller wanted him to get a bill introduced, contrary to what Nixon had in mind; presumably they were working together, but Rockefeller wanted his own bill. So he asked two people to work with him. He asked Wilbur Cohen to work with him, and Wilbur Cohen said he needed a draftsman, and he got a fellow by the name of Allanson Wilcox. Wilcox was the General Counsel, who had left when Nixon came in. Neither Wilbur nor Allanson knew anything about the technicalities. So they made a request that I should help them. So I was drafting legislation for Rockefeller, with Allanson Wilcox, for Wilbur Cohen, to be presented to Rockefeller, and Rockefeller was going to bring this bill to the White House and all that. That was very interesting. I never got to talk to Rockefeller, but I got to talk to his assistant. And there was one time when they wanted to talk to Wilbur Cohen in Albany. And I don't know if I did the right thing or not. But Wilbur Cohen suggested that Allanson Wilcox should come in and he and I should go to Albany. And Rockefeller was going to have his plane fly us up there. I felt I'd never get that opportunity again, but I felt I couldn't do it without at least telling my supervisor. And he said, "No." So that one episode of 15 minutes of fame, and I never got to ride on Rockefeller's plane. But Allanson Wilcox did go up; they went to see Rockefeller at the mansion and they had dinner with him, and they talked about the bill and all that. And I said to myself, "What would he have done to me? Thrown me out?" Meantime, I ran into some personal problems. My daughter had gotten married, she had a child, then the marriage was breaking up, but she was living in Columbia then. And we were having some real tough problems. So I went to Irv Wolkstein and Irv Wolkstein, by then, was in the Bureau of Health Insurance. And I said, "Irv, I got a problem; I've got to get back to Baltimore. Do you have anything for me to do?" He talked to Hess; Hess says "Sure, see if we can do something for him." So he got me back to Baltimore. And that's how I got to be in health insurance. Now we're talking 1969. Q: Now the Rockefeller bill that he was trying to draft, did any of that go into the family-assistance plan that Nixon eventually put forward? Levine: I don't know; I don't think it did. The family-assistance plan came in much later. Rockefeller wanted to show up Nixon and make sure he got something, and Nixon wanted to give this guy a break; so Nixon figured "I'll give this guy a break." So he had to come up with it; he couldn't come up with a lot of stuff. Q: So then you came back to BHI? Levine: I came back to BHI. And they gave me a job which involved the teaching physicians. Do you know about teaching physicians? Q: I know what they are, but I don't know what we had to do. Levine: They were just taking money and not doing anything. They were really strong. What they would do was the teaching physician would go into a hospital, like a county with all-charity patients. The physician would put his name on the form; he is responsible for this patient. Dr. Jones never saw the patient. The resident or an intern saw the patient. And then they would file a claim for every day of service. But Dr. Jones never saw the patient. These were all charity patients. And it turned out that they had almost $1,600,000 of government services that were not rendered. And this came before the Senate Finance Committee at a hearing. And the Senate Finance Committee--one of the staff members by the name of Jay Constantine called up Tom Tierney and said, "You son of a gun, you better go get that money back, or else we've got you." So they had to do something about these teaching physicians to get the money back. That's when I came into the picture. I worked for Irv, and he said, "Look, see what you can do with this." And so, for a year and a half, that's what I did. It was good work, it was interesting work. We found out that this kind of stuff was going on not only with Cook County Hospital, but apparently with every teaching hospital: Massachusetts General in Boston, one in Atlanta, Georgia--they have a big hospital down there. Johns Hopkins was involved. It was all over the country. And that's when I started to travel all over the country. What we had to do, you couldn't review every case, they might have had 3,000 or 4,000 cases, so we would usually get the names of all the numbers and run a sample. So we'd come up to these guys and we'd give a sample of 75 cases that we wanted to review. And we'd do 75 cases and find that the overpayment was, say, $205,000. Then we'd estimate the total overpayment from the sample cases. And the hospitals said, "Oh boy, you reviewed 25 cases--or even 75 cases--and you told us that we owe all this money. Come on, we're not going to give you any money." It was terrible. And they said, "We don't know how you adjudicate these cases." Every case, we had to go through every case that we adjudicated and show how we arrived at that figure. They were tough. You know, we were talking to their lawyers who would say stuff like: "What do you mean, you guys are reviewing it? This is the doctor's decision." "Well, he didn't sign it," we would say. "What do you mean, he didn't sign it, he's not supposed to sign it--he's not a bookkeeper." It went like that. Anyhow, I worked on that in 1969 until about 1970. We collected some money--actually repayments--some money from claims. By the way, they stopped paying off, no payments were made to teaching physicians, they suspended all payments. Everyone got fixed up, and straightened out, then they started to pay physicians, but they recovered by not paying old claims. But it was a messy situation. Cook County was especially tough. Somehow, they managed to get some dough out of them. Then about 1971, the Bureau of Health Insurance was reorganized; the whole overpayment situation went into a different area, so I was taken away from that. And I went into the Division of Technical Policy. Litigation was coming up now, so I got involved with litigation. A lot of technical things were coming up. And then in 1972, were the 1972 Amendments. There were two provisions in the Social Security Act that are still there, that I wrote. One of them is--I don't think they'll ever change it--the retroactive disallowance. Q: What is that? Levine: When a person goes into a hospital or nursing home, and stays there, and the claim for reimbursement is disallowed, they have to go back and collect. Meantime, Medicare has been paying this. And this fellow Cox says, "You've got to do something about retroactive disallowances." So I drafted the "good faith" provision--title IX or whatever it is. If you get services rendered by a provider--a hospital, a doctor, or whatever it is--and the doctor provides it to you in good faith, and then we finally determine that it's not covered, then there's a waiver provision, they waive it. That was a big help. And that's where my friend and your friend Rhoda Greenberg (Davis) came in--if you see her again, ask her about the retroactive provision. The other provision, which I was really proud of--I don't think anybody will ever change it--is the statute of limitations on State and local coverage. You probably can't even find it. I forgot the details on it; but all I know is that it was a tough situation. Tom Hart and I worked on it, and nobody dared touch it. It was so technical, and framed in such a way that if you touched one provision, 13 provisions down the road had to be affected by it. And no one did, even when it went into the draftsmen for the Ways and Means Committee, they didn't touch this thing. I think retroactive coverage is still in there, because I had a claim for myself involving it. I went to Johns Hopkins with an eye problem and they took a photograph of my eye. And Johns Hopkins sent in a claim, and Medicare said, "it's not allowed." And I got a letter from Blue Cross-Blue Shield, the carrier, "Since you didn't know it wasn't covered, blah, blah, if you pay this bill, we will reimburse you." Q: So, you became a beneficiary of the provision you wrote? Levine: I became a beneficiary. As it turned out, it was covered under the health insurance program of the Federal Government, so they paid it. And Hopkins never billed me. If Hopkins had billed me, I would have paid the bill and sent this bill into Blue Cross-Blue Shield and they'd have paid me. So I was the beneficiary of that. I got to know Rhoda first of all in the teaching-physician case. I went up to Boston to talk to Massachusetts General Hospital and the Regional Office. Rhoda was at the Regional Office then. And we talked a little about that. It was obvious that she had known a few people up there, one of them was Sandy Crank. Sandy was the Regional Rep for health insurance, and Rhoda worked there. So I got to know Rhoda. I went up there and talked to her about the situation. I don't know if I had any intimate details on the situation; I was dealing with other people in the region. And then, Rhoda had the job--an executive development program where they'd take a person and bring them down here for 6 months or send them some place else for 6 months. So Rhoda left Boston and came down on this program. They sent her into operations work. So I talked to her. And what they had to do is that after a while, she had to go and get herself another place to go. So she came up to me, and it just happened that at that point, certain things happened in the division that I had. And there was a fellow who dealt with technical aspects of it and freedom of information. So I said to her, "There's a job over there. You want to go for that job?" And she said, "Sure." She started to work in the division where I was. And then, the time came where she had to go to some place else, or her time in the program had ended. So she said, "I've got to find another job here." We had a little difficulty filling it with her; you file an application for the job, you put down your qualifications, do they still have that? You're in the top five, you've got to pick one, you make certain you pick the right person. For some reason, we had a problem; it looked like she wouldn't make the top five. We did something with her; I forgot what we did; we did something that brought her into the top five. It wasn't kosher, but we did it, and we selected her for the job. And so there Rhoda was in this technical policy job. And along comes this waiver of liability. And that did not fall within her bailiwick; it was someone else's. And the fellow who had it didn't know what to do; he didn't know how to handle it. So I said, "Rhoda, do me a favor, take this project." And she put her heart and soul into it. And I don't know what the rules are now, but if I'm getting paid, they must be the same rules. And that way, she got to see a lot of people. Then there was a vacancy in the Tierney's office and he took her on. Irv Wolkstein had recommended her and I agreed; I said, "She's done all she can here;" there wasn't very much for her to do, and there was an opportunity to go up there and she did and she went on from there. So that's how she stayed in Baltimore. If she hadn't gotten a job with me, I think she would have had to go back to Boston. And I don't think she wanted to go back to Boston. She wanted to be here. Well, I got myself up to 1972. Things just went along in 72-73. The work with litigation is getting pretty hot and heavy. There is a lot of litigation because people are suing. Meantime, oh and another thing happened, the Provider Reimbursement Review Board was formed." Q: So we're having litigation over what kind of issues? Do people sue because they did not get a reimbursement? Levine: Reimbursement and reimbursement issues, overpayment issues, just general interpretation of the law. They didn't like our regulations and that kind of stuff. Specifically, I remember a few cases that really were very interesting. And then the Provider Reimbursement Review Board was enacted in part of the 1972 Amendments and so that fell within my division and so we had to constitute the Review Board, get the names of people who would serve, things like that. So we had to do some canvassing with people on the side. I had a fellow by the name of Stan Katz. Have you seen him or heard that name? I guess he's still here, maybe he's retired, I don't know. So we worked up the Provider Reimbursement Review Board and set them up in business. So that's a lot of the work I did in 73 and 74. In 1975 Irv Wolkstein--he is in charge of the Policy Branch and I am one of his assistants--and he retired. So Tom Tierney put me in charge of the Policy Branch. At this point I retired, and the next day I became a reemployed annuitant. The reason for doing that is, because there was a tremendous amount of inflation in the economy, so retiree benefits were shooting up, 10 or 15 percent increase each year. . . Q: From COLAs? Levine: Yeah from COLAs. And I said "Gee I want to get a piece of that action." So I got to retire, but I didn't want to leave the job. So I went up to Tierney and said "Look what difference does it make to you?" "So let me retire so I can get the benefit of the COLAs and reemploy me as an annuitant and I'll come back the next day." Well, Tom wasn't too happy and he didn't know what to do with it. So he went up to see Cardwell, who was Commissioner, and Cardwell went, "All right let him do it." So at the end of 1974, and before January 1, 1975, I retired. I got reemployed as an annuitant the next day. But the annuities were shooting up a tremendous amount due to the COLAs, and Congress finally caught on and changed that. So now I had Irv Wolkstein's old job. But I was a 15 and Irv Wolkstein had been a 17. And they figured they could give me a 16, if a 16 became available. And when the time came to advertise for Irv Wolkstein's job they decided to fill that job and they came to the conclusion, somebody came to the conclusion, that since I was a reemployed annuitant I couldn't hold that job. That was a grade 16 job and no reemployed annuitant could hold it. Okay if I can't hold it, I can't hold it. That's no big deal but I still stayed on the job as the deputy. So they gave the job to another guy, a fellow named Mel Blumenthal. I used to work with Mel in the General Counsel's Office. I never did particularly care for him, he was a nice guy, but I never cared for him. Mel Blumenthal was Packer's assistant on coverage and wages, I was Packer's assistant on all the other aspects. But Mel and I never hit it off--I just didn't cotton to the guy. So now Mel Blumenthal was hired as my supervisor and you know I figured that there is something more in life than working for Mel Blumenthal, so I just said "The heck with it." June 1976, I just retired. I shouldn't say retired, I just left because I had already retired, and I just left. But the funny thing about the whole thing is that I had been working on the problem of health insurance dealing with reimbursement for costs involved in getting insurance. Q. Getting insurance? Levine: Yeah getting insurance. Insurance coverage is very expensive. So some of these hospitals wanted to self-insure. And the rule was that if you self-insure--even if you put your money in a fund for self-insurance, it was just putting it in another bank account--it was not a reimbursable cost. And so just before I left I got the policy changed, as a result of all the pressure from hospitals, and self-insurance was a reimbursible cost. So I hadn't been out for about a month--you know when I got out, I did a lot of interesting things, I went to a reunion up at Cambridge and I went traveling to Italy with my wife, and I took my grandson on a trip to New England--and when I got back there was a telephone call from an insurance company in Washington, they were going to sell self-insurance programs to hospitals, so I got involved as a consultant to them. So I went to Washington and began doing the same thing I was doing before, except on the other side of the program. And there were times when I would get involved in some problems I wished I had not worked on when I was in the Bureau of Health Insurance, because there might be a conflict of interest. In those situations the company would say "okay we'll make out, forget about it." And I did that for two or three years and I did it primarily to get myself a wage record, so I could get Social Security benefits. Q: Let me give you my usual last question, it's just to give you a chance to sum up your attitude about your career and your experiences. Did you enjoy it? Did you like working for Social Security all those years? Where you glad you did it? Levine: Well, it's difficult to say. I always say to myself what would have happened if I hadn't been certified and I had to struggle as a lawyer in New Jersey? Things changed after a while, I mean during the war time, there were a lot of offerings for lawyers, and I was never cut out for the practice of law. What would have happened? It is difficult to say. So at that time the only alternative was this possibility. I just don't know what I would have done. I didn't have any idea of how to approach the thing, I wasn't a member of the bar yet and I was still working for $50 a month, and in the meantime I was going to get married, I had to do something. So the job was the only thing, the only available option I had at that point, and having taken it I wasn't happy I had taken it, because I had never felt clear in my own mind this was the right course. Certainly, as time went on I saw that I might have been able to have made it in the law because there were a lot of openings in the work. I was deferred (from the military) because of my eyes, I certainly could have gone into a little law firm. Who knows what would have happened? Was my life in Social Security a success? The answer is "yes." Did I enjoy it? Yes and no. There were sometimes when I did not enjoy it. I really did not. I mean you work on equitable entitlement for a year and half and it comes to the point that you don't enjoy it anymore. And working in the General Counsel's office for 11 years was a really enjoyable experience. And, in general, the life was a good life and we had two children and my wife, her health was good and we had a car and we would go riding, we bought a house, and you know the usual things that happen at that age, so I didn't have any problems. Then going into the Division of Program Operations. That I look at as not a very good job, I should have stayed in the Office of General Counsel. I think I would have made the same kind of advancement. But then I say if I'd stayed in the Office of General Counsel I never would have gotten to the Bureau of Health Insurance. I never would have been able to develop this whole knowledge which helped me later on going into law practice. It was not a very interesting time. I didn't like the whole simplification process, no one was interested. The only guy that was interested was Bob Ball, and he had a lot of other things. Alvin David, who was in charge, didn't care about it--couldn't care less. Jack Futterman was only interested in Jack Futterman, so he couldn't care less. So I was left alone. And the people around me in the various branches thought if I failed, so what? They weren't anxious to help me. So I think that whole period was a not a happy one. But then I went into disability and that was a very good experience. I enjoyed it. I always say to myself why did I leave disability and go to the General Counsel Office? It wasn't what I thought it would be, and I guess I was mislead by the fact that I like legislation, but on a part-time, not a full-time, basis. Then when I came back into Health Insurance I thought it was great. But then this other thing came along. It was okay, and all of the information, all of the knowledge, I had gotten from working in health insurance I was able to put to good use. Even today, my background of legislation comes in very helpful, while I live here, because I'm involved with the Office of Aging on developing legislation for homes like this. If I looked at it overall, except for these periods when there was a certain amount of unhappiness, I would say it has been a good career, I've enjoyed it. Every once in a while, I see one of those guys who still remembers me. One of those fellows who was at Rhoda Davis' retirement party--Gil Fisher. You know him? When I was working in the, I guess the General Counsel's Office, he was just a little guy that would come in and work, and he remembered me, and I didn't remember him. He paid me one of the greatest compliments, he said "Oh sure I remember you, you're a legend around here." So really he made me feel good that he would say that, but that was only because of the technique that I had developed in legislation, in drafting legislation, and it was a talent that no one else had and it's a talent that you can't train a person in. To be in drafting legislation you've got to have it in your blood, and I think it came to me only because of my mathematical background. I enjoyed doing it all of the time. Well that's it! |