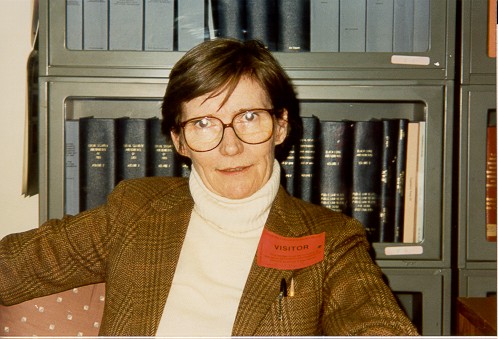

Mary Ross

Mary Ross during her oral history interview, 10/26/95. SSA History Archives.

| Editor's Note |

| In the Fall of 1995, shortly after the launch of SSA's Oral History Project, I contacted Mary Ross and asked her to be one of the first participants in our Project. Somewhat reluctantly, she agreed. Her reticence was due to a kind of modesty on her part--she was concerned that she might not be able to do intellectual justice to the subject in such a casual setting. Mary was intellectually intense, with a career-long habit of painstakingly researching and documenting her ideas and conclusions. Her office at SSA, and her home as well, were filled with books, reports, research papers, and the like, which she would consult in detail whenever she faced any task of work. As we started our first session in October 1995, our plan was to do a long overview of Mary's career, and then to focus in detail on several key areas in which Mary played significant roles. Our second session, which took place in February 1996, was to focus on the creation of the SSI program, and especially on the Family Assistance Plan (FAP), which was the precursor to SSI. I think Mary's plan all along was that she would assemble her papers and records and engage in an extended research effort prior to each topical interview--so that she could, in effect, document her oral history interview in much the same way she would document a research paper. This was, of course, far beyond what I expect from an oral history interview, and far beyond what most interviewees would even consider doing. As I always try to explain to interviewees, an oral history is not like a book or a research paper. It is by its nature less rigorous, more informal, more impressionistic--indeed, that is its charm and principal value. But people like Mary, with life-long habits of intellectual scholarship, sometimes have a hard time accepting this. In the four months between our first and second sessions, Mary was planning to research the paper records of FAP and SSI and come to Baltimore prepared to footnote and document everything she told me. I thought all along this was an unrealistic demand to make on herself, and although she did do a surprising amount of preparatory research for our second interview, she clearly had concluded that she would be unable to devote so much time and effort to every major topic we intended to cover. So as we were doing her second interview, she was visibly agitated over what she saw as the inadequacies of her documentation. At the end the session, she abruptly announced that she was breaking-off her interview because she simply could not devote to it the level of scholarship she thought was required. I was of course very disappointed at Mary's decision, but it was clear she had made up her mind, so our interview ended abruptly, with an incomplete product in hand. I had an initial draft transcript made of our two conversations, and put it aside, intending at some point to approach Mary with the idea of resuming the interview. Unfortunately, I let the matter ride too long, as other work intruded and time passed more quickly than it should, and the opportunity was finally lost when Mary died on March 11, 2001 at her home in Washington, D.C., after a bout with lung cancer. The week before her death, in a phone conversation with Bob Ball, Mary expressed an interest in resuming our oral history interview and she asked him to convey this message to me. Ball called me on Wednesday, after talking with Mary, and suggested I call her and schedule some sessions. I put off doing so, thinking I would contact her the following Monday when I was planning to be in Alexandria, Virginia for an interview session with Mr. Ball. My intention was to call Mary from the Ball home and suggest to her that I might stop by on my way back to the office. When I arrived at Ball's home on Monday morning, he informed me that Mary had died over the weekend. Although we all understood that Mary's condition was grave, I think the suddenness of her passing took us by surprise. In addition to the personal loss that many people feel on Mary's passing, I regret very much the lost opportunities I let slip away to more fully document Mary's career and the important Social Security history she helped to make. But in order that the work we did do together not be lost, we are publishing here the transcript of her incomplete oral history interview from 1995-96. Due to these circumstances, it is important to take note of the fact that Mary did not have an opportunity to edit this transcript, as we would do in the usual course of things. Since Mary was so concerned about the precision of her account, this is especially important, since small errors inevitably arise in oral history memoirs. Generally these errors are corrected in the editorial process, which involves an initial editing pass in my office and then a second review by the interviewee. Mary, with her intense intellectual precision, would certainly have provided a rigorous editorial review, had she had the opportunity to do so. I have done my best to review and edit the document as carefully as I can, but if there are remaining errors, they are entirely my responsibility. Despite these several limitations, Mary Ross' oral history interview is a valuable contribution to the literature on the history of Social Security. I learned many things from my conversations with Mary, and I think we are all lucky to have even this incomplete record of the career and contributions of Mary Ross.

Larry DeWitt |

OBITUARY (Note: This obituary was written by Mary's friend, Johnnie Albertson, and portions of it appeared in the Washington Post of March 16, 2001, pg. B7.) |

Mary E. Ross Retired Social Security Official Mary E. Ross, 62, a career employee for 34 years of the Social Security Administration, died of lung cancer at her home in Washington on March 11. For most of her career with SSA, Ms Ross was a Senior Executive and Director of the Legislative Reference Office of the Social Security Administration. Born in Philadelphia, Ms. Ross came to Washington as a child with her parents. Her mother was Elizabeth Ross, Deputy Director of the Children's Bureau. Among her mother's federal accomplishments was the securing of government recognition of professional social work. Her father, Michael Ross, born in England, was active in the labor movement in England and became Director of International Affairs for the CIO. Both are deceased. A graduate of Madeira School and of Wellesley College, Ms. Ross began her government career as a student intern with the Social Security Administration in 1959. Following her graduation from Wellesley College in 1960, she was appointed to the position of Social Insurance Research Analyst in SSA's legislative planning department and, from 1968 to her retirement in 1994, played a key role in the planning of major changes and improvements in the Social Security program, particularly in the areas of retirement and survivors benefits. She was appointed to a Career Executive Assignment in October 1972 while serving as Director of the Division of Retirement and Survivors Benefits in the Office of Program Evaluation and Planning. A recipient of top Agency awards throughout her career, Ms Ross was active in the many organizations and forums involved in the examination and improvement of the Social Security program. She was a founding member of the National Academy for Social Insurance and participated as an advisor and key staff member in the several official Advisory Councils from 1971 through 1996, including the famous Greenspan Commission of 1983. Robert Ball, Commissioner of Social Security from 1962 to 1973 and an important figure in the development of Social Security over the last 60 years said today, "Mary Ross made many important contributions to Social Security, particularly in the areas of policy and legislation. She was a tremendous help to me personally during the 11 years I was Commissioner of Social Security and during the 25 years since. She was a great student of Social Security and a lovely person." Ms. Ross leaves no survivors. |

| Q: Mary, let's start if we can, by having you tell us how you began your career with SSA and give us an outline of the jobs you had over the years and what positions you were in. Ross: Well, it was all kind of a bumbling, inadvertent stumbling into something. I was between my junior and senior year in college. I didn't know what I was going to do that summer. I wound up going to a cocktail party that was given by some people who knew the Balls, who knew the McKennas, and various other people associated with Social Security, many of whom were at this party. I was kind of an awkward, little, shy person who, when they said: "What are you doing this summer, Mary," I would kind of look uncomfortable and say: "I don't know." Leona MacKinnon, who then worked in the Office of the Bureau Director--this was the summer of 1959, so what's now SSA was then the Bureau of Old Age and Survivors Insurance-- said: "Oh, we can use student assistants in the summertime. Why don't you come and work for Social Security in Baltimore." One thing led to another, and I found a car I could borrow. I did work for Social Security that summer. They hadn't yet moved into the Altmeyer Building, which wasn't built until 1960, so that was when SSA was downtown. I worked in the predecessor to what became most recently OLCA, the Office of Legislative and Congressional Affairs. It was then called the Division of Program Analysis (DPA) and reported directly to the Bureau Director, who was then a person named Victor Christgau. Bob Ball was the Deputy Director, and really the one with whom we had the most communication. He had previously worked in DPA himself and he was, in large part, running SSA. Even though he was Deputy Director, he was really running the Bureau as it was then. I came to work for Alvin David who was the director of the outfit. We were located in the Equitable Building on Calvert Street, near Baltimore Street, downtown. We parked in public parking up Calvert. I worked in the front office. Up until fairly recently, Congress wanted printed hearings, and they had printed an index to the hearings and they had stopped doing that. My assignment that summer (I can't believe I did this) was the Index of 1958 Hearings. It was totally tedious and did not result in a usable product, though I learned a certain amount about who were the figures in Congress. I sat in the middle of an office where a lot of traffic was going on. It was kind of a control point for assignments and for correspondence, and it was physically located so it was just outside the Director's office; anybody who was going or coming went by. I got to know some of the people and I enjoyed working with them. I never thought I'd work for the government as a career. Wilbur Cohen's son, Chris Cohen, was also a student assistant in that office that same summer. His assignment was to update DPA's Claims Manual. That summer passed and I went back to school and graduated with no notion of what I wanted to do. My parents had the notion that either I continue in school or I become self-supporting, and I certainly was through going to school. At the end of the summer I had taken the appropriate Civil Service tests that we had to take then. I came back to see if I could get a permanent job in the same place I had worked. A bargain was struck and I and another person (who put the outfit over its staffing ceiling, we later learned) began working here. By this time it was out here at Woodlawn (September 26, 1960). I had been a grade 3 as a student assistant. I was permanently hired as a grade 5. I had been a history major. I had absolutely no credentials of any sort. I was in an outfit that had pretty clear career ladders. If you progressed reasonably and didn't screw up, you could more or less expect to be promoted every year or two. In my case it was more or less every year. In the Division of Program Analysis there were five branches, two of which did the kind of work that people now think of OLCA doing -- preparations for Congressional appearances, hearings and the like, defending and explaining the program, staff work for the Commissioner's Office that involved program planning and program rationale. One of the two divisions was then headed by Irv Wolkstein. It was called Coverage and Disability, but its main activity already was beginning preparation for health insurance. The other division was just called Program Planning and it was the predecessor of what is now the Division of Retirement and Survivors-at least until recently. Are they still divided into divisions? Q: No, they are combined now. Ross: We have come full circle. Within that division they had kind of a neat arrangement. They were divided into groups. There were five groups, and each had a group leader who was probably a grade 12, and maybe three analysts and a secretary. For training purposes, which is what I was involved in for the first year, you worked in one of these groups for a reasonable length of time and then you rotated. They were divided by subject matter so you could get familiar with some aspect of the program without having to be overwhelmed by the whole thing. I don't know how many people catch on to what it's all about now. Even then DPA preferred to not hire people fresh out of college and right off the street like I was. They preferred to hire people with field experience. For those of us who didn't have field experience, we would be sent to a local office for a brief time. After about a year I was sent to a downtown district office in Philadelphia, for about a week. I don't know if you would call it suburban, (I guess it's suburban now) but anyway a less urban center, which was Westchester, Pennsylvania. I also spent a week in the Philadelphia Payment Center, as it was then called. I came to work at the end of the Eisenhower Administration when just about everything we did (as near as I can recall) was shrouded with a wonderful paragraph that explained that no matter how good somebody's idea was, it was bound to have some cost and therefore, couldn't really be entertained at this time. In a way, they were beleaguered then as the program has been at times since. The OASI Trust Fund had been operating in the red. It had been taking in towards the end of the 1950's slightly less each year than it was paying out. A very vocal critic by the name of Roy Peterson was writing articles about the coming "den of inequity that would be discovered when this basically bankrupt program fell apart." We were busy debating it, making public replies to public newspaper statements. What was somewhat worrying was that we were enabling him to make better and better arguments by our erudite responses. Then Kennedy came in the following year. The theme was pushing Kennedy's Social Security promises that had been in the Democratic platform. Medicare was clearly in the wind, but it was not the immediate priority. Part of Kennedy's initial campaign had to do with the widespread unemployment and so-called structural unemployment of older people who were out of work and didn't stand a prayer. They had been out of work for extended periods. Hence, he had recommended legalizing the definition of disability, which did not go through that year; lowering the age of eligibility for men on an actuarially reduced basis; increasing benefits for widows; and several other things that were enacted in the 1961 Amendments. Following that, my career consisted of first working in the little group that worked on age of eligibility, and then working in a little group that worked on the retirement test and Regulation 1, and disclosure issues. (Editor's Note; Regulation 1 is the SSA regulation regarding disclosure of Social Security records.) Then I worked in a little group that (oh, what a nightmare!) did definition of wages. I then worked with a group that did benefit amounts, which was a breath of fresh air. I finally moved into the group that worked on financing dependents' benefits and stuff that didn't fit into one of the other groups and that serviced the Advisory Council.

A lot of what we were doing was sort of being ready. Medicare had the spotlight, and there were a bunch of cash benefit amendments that were ready to go once Medicare was set, but the strategy was not to allow any more cash benefit increases, and certainly not to allow any that would involve increasing the payroll tax, until Medicare was launched. Throughout the first 5 years I climbed up the ladder. I finally got to be a GS-9. I forget what we made then; it was probably about $9,000 or $10,000. At this point I felt I could begin to breathe a little bit. I hadn't taken any leave and I had mountains of leave. Finally Medicare got passed, and the 1965 Amendments got passed. I worked on the 1965 Advisory Council Report at the beginning of 1965. By then maybe I was a GS-11, or a13 -- some place in there. At the end of 1965 I took leave for 6 months and traveled and went around the world. I came back to a new world in the spring of 1966 where I guess by now I was a senior analyst. We had gone now from five groups down to four sections. And I think the top structure had moved up. The branch chief was now a 14, not a 13. The whole air had lightened a little. Johnson was now President, and I worked in the financing area during the 1967 and 1968 Amendments.

Johnson had tremendous ambitions and not a whole lot of available money in the Title II program to do things with. We had a lot of false starts and developed a lot of wonderful schemes with large benefit increases and wound up paring them back. This was unusual to me. In cash benefits, we wound up doing a lot of staff work on the Hill during that period. The AFL-CIO was pushing a Kennedy bill (Editor's note: Senator Edward Kennedy), and Johnson wanted not to have the AFL-CIO to be able to pull off something more generous than he could pull off. We were doing staff work with eyes in the back of our heads for both the Administration and the liberals in Congress at the same time. The group leader was Frank Crowley. A lot of people who worked for OLCA at that time wound up on the Hill. Some of the guys who worked in Medicare wound up on the Hill after a brief stint implementing Medicare. At that point the group leader I was working for, Frank Crowley, left and went to the Congressional Research Service, and I became Acting Group Leader. I guess we had now become the Office of Program Evaluation and Planning, and what had been branches had now become divisions. I became Acting Branch Chief in the Program Evaluation and Planning branch. I did that for a very brief period. Health insurance was still administered by SSA, and by then we had the Division of Health Insurance in OLCA, and the Branch Chief job in the Health Insurance Benefits Branch became effective. I worked for about a year as Branch Chief in the Health Insurance Benefits Branch. At that time we had the Advisory Council on Medicare for the Disabled. I guess their report was submitted at the end of 1968. It seems to me I left there shortly thereafter, and became Deputy Division Director back in Retirement and Survivors Insurance. I was Deputy to Betty Sanders who had been Director of that Division since before I came, probably since 1957 or 1958.

By now we are in the fall of 1969. My mother died, which meant I inherited this house that I still live in, in Washington. Betty Sanders had been saying for years that she was going to retire when she turned 65, and I was kind of an heir-apparent to the Division Director here in Baltimore. I had no idea of what I wanted to do. I didn't know if I wanted to live in the house and work in Washington. I didn't know if I could live in the house in Washington and work in Baltimore. Although I always had my eye on that job in one sense, by this time I didn't really know if I wanted to be responsible and grown-up and all that good stuff that it was going to take to do it. I got assigned to Alvin David's front office, in which they set up a GS-14, or was it GS-15, job for me. It was a Social Insurance Research Analyst job. It was a lot easier to do things back then; and they detailed me to Washington, which let me live in the house and gave me some time to figure out what I wanted to do. This now was when the Nixon Administration Family Assistance Plan was beginning to move. So I was lurking around the Department working as kind of a Social Security liaison or freelance analyst type person. Sometimes I was working for Tom Joe on various projects. I'd go in to try to figure out what was the ideal way to organize the Family Assistance Plan, and what should be the appropriate relationships between HHS and Labor, which caused me to learn a great deal of discouraging news about the WIN Program, which was the Work Incentive Program then, and AFDC. There was a split jurisdiction between HHS and Labor. I was detailed to a guy named John C. Montgomery who was hired by the Secretary's Office to kind of oversee the whole Departmental effort to provide the logistics to further the Hill activities and begin planning for how they would implement the Family Assistance Program, once you got it through Congress. I guess it was as Tom Joe's person that I attended a bunch of the planning meetings with Bob Patracelli, the Assistant Secretary for Program Evaluation and Planning, or whatever was that predecessor outfit. That was an exciting period. Then, of course, it became clear that Family Assistance was not going through and SSI was. In the meanwhile, the Nixon Administration was also simultaneously pushing automatic adjustments of Social Security benefits, which was a big deal. Some place in the course of all this, I came back and did take the Division Director's job in DRSB. I sort of handed-off SSI when that got serious. I worked for a while in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Legislation. I guess the deputy for Welfare Legislation was then Jim Edwards. John Trout and I both worked there. I came back to OLCA and pretty soon John Trout came over to OLCA. We were back into clearly cash benefits, and a separate staff was set up to worry about SSI. The automatics were then added to a debt -ceiling bill. It was a very chaotic legislative period, but I guess that's saved for another session. By now I decided I could live in the house in Washington and work in Baltimore, and stay over in Baltimore a couple of nights a week. I would try to arrange to get myself sent to Washington every so often. I'm trying to think when the super grade came through. I was by then a grade 15. They tried to get a grade 16 for Irv Wolkstein, who had been head of the Health Insurance Division. It was in the early Nixon years. They had been trying to get a super grade for one of the Division Directors in OLCA for a long time. They first targeted Irv Wolkstein's job because he had done such a superb job in the Medicare fight. He had remained on as Division Director until 1968, and that had fallen through. Then they had tried to set up a super grade Division Director to run SSI because SSI legislation indicated that there would be room for additional high grades to administer the program, and because it was thought that somebody with both Social Security and welfare could do it. There were oodles of rationale. I remember writing that up six ways to Sunday. That did not come to pass. I was by then very cynical about the whole operation. I was sure it was going to come to nothing. They wrote it up for DRSB, which was the Division of Retirement and Survivors Benefits, that I was in charge of, and it went through. Q: So were you the first super grade then in the organization at that time? Ross: Well, no. The Division Director, Mr. David, was a super-grade and his Deputy, Jim Marquis, was a super-grade. Alvin was a 17. I don't think there was an 18. It seems to me McKenna was a 18, and some of the big operating staffs. Obviously, Joe Fay was, but I'm not sure whether Alvin was a 18 or just a 17. And the 1970's perked along. Two things were immediately clear: 1. There would have to be legislation to repair the methodology