Oral Histories

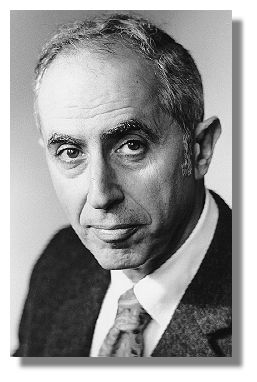

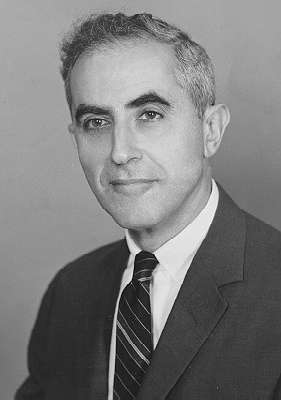

Alvin David

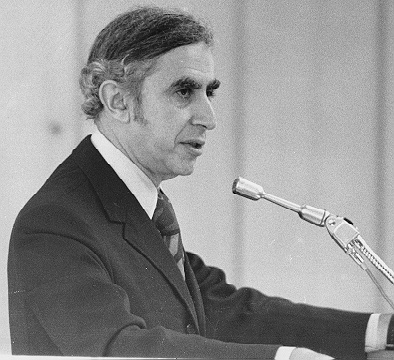

Alvin David, circa 1973

Photo Gallery

Alvin David, circa 1949.

SSA History Archives.

Alvin David, late 1950s.

SSA History Archives.

Alvin David, 1960.

SSA History Archives.

Alvin David, July 1966.

SSA History Archives.

Alvin David, speaking at a conference in San Francisco, November 1972. SSA History Archives.

Interview in the SSA Oral History Project

Interview with Alvin David, October 20,1997

Interviewer: Larry DeWitt, SSA Historian

This interview took place at Mr. David's home in Chicago, Illinois

Q: How did you come to work for SSA? What were the circumstances that brought you to SSA?

David:

I started October 10, 1936. Just before that, I worked for the Railroad Retirement Board where I interviewed somewhat like you do except I wrote up biographies of these individuals, all of whom had been dealt with poorly by the existing retirement system in the railroads. There were a number of railroads that had retirement programs and on paper they looked not so bad. In practice, they were terrible. At that time in 1936 The Railroad Retirement Act had been found unconstitutional. The case was being appealed to the Supreme Court and the attorneys were after stories about how poorly the existing retirement system worked. So I did a total of nearly 100 biographies.

Q: You were an employee of the Board?

David:

Yes, the Railroad Retirement Board. We were working with the attorneys. They were preparing the briefings for the Supreme Court. Then what I did was to carefully write nearly 100 biographies over a period of 6 months or so. I wrote in considerable detail about their railroad careers, how long they had worked, where and so forth. What had happened to them was that they were denied a pension altogether or were given only a very small pension. Because of the fine print in the pension plans themselves, you had to have a long period of continued service. If your service was broken for a period, you could be denied altogether. But one thing and another led to either rejection or complete denial of pension benefits. So I brought out these things in considerable detail and sharpness by presenting these specific cases.

That was the kind of background nobody had but me. I mean the people who were in Social Security at the time. Nobody had that background. Also I had read the book by Murray Lattimer, who was the first Director of Railroad Retirement. He was also the first Director of the Bureau of Federal Old Age Benefits, which was the predecessor of the Social Security Administration. I knew something about that.

Also I had worked as a labor adviser in the NRA--National Recovery Administration. All these things led me to be selected for a position at Social Security in the Bureau of Federal Old-Age Benefits which was under the Social Security Board.

Q: Now did they come seeking you or did you apply for this job?

David:

I applied. When I got into Social Security, I was placed in the Training Office. There was nobody there to train me, so I took off with the staff through the Printing Office, not ever having been trained which is not surprising because there was nobody there to train you.

People around were people who worked in the Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce in the Department of Commerce. They were the kind of staff who did budgeting and things like that. A lot of them showed up at Social Security. Others were staff or other employees from insurance companies that were involved with employee benefit plans. These were people who were insurance men or otherwise connected with the development of employee benefit plans. So there were Foreign and Domestic Commerce and insurance company people.

Q: Were there NRA people, maybe?

David:

I don't recall.

Q: In any case, you guys were starting this program up from scratch. There wasn't an institution there. You guys were putting together an institution.

David:

Yes, this was in 1936. The act had been past in August 1935 and the first tax collections were scheduled for January 1937.

What I did in the Training Office was essentially to go over the Title II provisions themselves and the Committee Report materials. So that the people who would come in for training could have some explanation. We would form discussion groups and would go through the materials line by line to try to understand what the law was saying by looking at the Committee Reports.

Q: One of the things we did in the early days was bringing a lot of folks into Baltimore for training classes--all the new office managers and so on.

David:

That's right.

Q: So you were part of that training that we gave to the new employees. You were researching the law so you could explain it to the new managers.

David:

Yes.

Q: That was very important. I have a quote somewhere from Altmeyer who said that training program was one of the keys to success of the early program.

David:

I think that is quite true.

The Office of the Actuary was established in early 1937. At that point I was recruited by the Office of the Actuary, despite that I had no claim to actuarial background. The Chief Actuary was named W. R. Williamson and his Deputy was Burchett Wyatt. Have you heard of him?

Q: Sure.

David:

Wyatt had his eye on me because of the kinds of things that he was especially interested in. He was especially interested in employee benefit plans. Also he had in mind a book on Social Security in operation and he thought I was going to be a good one for working on it, which it turned out that I was.

I can't recall very much about what kind of work I did in the Office of the Actuary except writing memoranda on the relationships between Social Security and the employee benefit plans.

More natural for me than the Office of the Actuary was the Analysis Division, which was established in 1937. In the Analysis Division we had a branch that was charged with planning where further steps were justified in the development of the Social Security program. I was there, doing that kind of work, during the end of 1937 and through 1938.

At that time we had considerable participation in program planning by the insurance industry in the form of the Chief Actuary for Metropolitan Life by the name of Houhaus. Houhaus was assigned by the company to come and work with us, and I am sure they were not doing it out of the goodness of their heart--they were hoping to influence the way things were going. They produced a paper called "Equity Inadequacy In Social Security," something like that. We spent a lot of time working on that. The atmosphere at the time was that these people were regarded as our helpers. They were not thought of as adversaries at all. As I look back on it, I think they were adversaries. They were trying to influence us in the direction of keeping these new programs from getting too big and too invasive of the interests of the insurance industry. But everybody worked together as friends. As I look back on it this seems rather strange. But it seemed to work. They didn't act as if they had an axe to grind.

Q: At the same time wasn't there pressure in the other direction, pressure to speed up the benefits, make them more generous and make the program bigger? Didn't you have competing pressure on the opposite side?

David:

Indeed it was. The pressure to pay first benefits in January 1940 instead of 1942 was quite strong. I should note that this was a puny little program and the pressure groups that might have been interested were not that much interested in those days. Organized labor was interested in unemployment. The social work profession was interested in public assistance and maternal and child welfare.

Q: So who was pushing from the other side?

David:

Not very much, not very many. That was one of the strange things. These benefits to be paid in January were about $20 a month. Even in those days $20 was not very much.

Q: I sometimes get the impression that there was a philosophy on the part of the officials who ran the program that they wanted to expand the program. Some of it came from a natural belief in expanding the program on the part of Altmeyer and people like that. Is that accurate?

David:

There was of course a tendency to want to build-up what you are responsible for--that is a natural bureaucratic tendency. But Altmeyer and Wilbur Cohen were strong believers in what they were doing.

One interesting thing to me in relation to that was that we were not conscious of any pressure from the Administration--at least at my level we weren't. In later times we heard "It's the economy's stupid." Now nobody ever said anything like that in that time. Nobody we had any contact with ever said you had to get benefits underway by 1940. Nobody said that. We were utterly unconscious of that. We had some thoughts that benefits ought to start earlier, but we had no sense that there was any political weight to the idea, it was just too small a program.

Q: So the idea that it should start earlier was just kind of a fairness or an equity idea?

David:

No, it was the reverse of that. It was the opposite of an equity idea. The insurance

companies were interested in the traditional way of financing retirement systems, which is start building up a fund. When you had enough money in the fund, you started paying benefits.

Q: Which is how it was designed in 1935. You were going to build up the funds for 1937 to 1942, right?

David:

Yes. The traditional way in private pensions and industrial pension plans was to start building up funds and later starting to pay benefits. The 1935 law was based on that general approach which was based on total accumulated wages, and the eventual benefits were pretty small. The biggest thing that came into the 1939 Amendments was to depart from reliance on total wages and total years of coverage and go to average wages. That was a big historic step. In the 1935 act we used total accumulated wages.

Q: And the effect of that was to make the benefits more generous?

David:

Yes, much more. It made all the difference.

Q: So it was really adequacy that was the concern in the 1939 Amendments, not equity. It was the adequacy issue.

David:

Yes. The efforts of the insurance people were to bring equity and adequacy into balance. They were in favor of averaging in part and also in part of a credit for years of coverage. It was a combination. Our plan included average wages plus credit for years of service. Which we later realized is not the best way to go.

But we were under the influence of the old Act and the industrial pension plans, and probably the insurance industry too. So we relied both on average wages and total coverage--1 percent credit for each year of coverage is the way I remember it. This was the last plan we sent to the Advisory Board.

Q: You had a whole variety of plans that you presented, right?

David:

Yes, there were 14.

Q: Did you guys work closely with the Advisory Council? Were there a lot of exchanges of memos and ideas?

David:

It was a one-way flow, we sent them stuff. We did not work with them, at least not at my level, maybe Altmeyer and Cohen did. We worked closely to the extent that I wrote the first draft of the Advisory Council Report in December 1938. Very little of my work ended up in the final report. But I did write the first draft. I thought mine was better.

Q: I suspect it was.

Now the other big thing, of course, that happened in 1939 was the addition of dependents and survivors benefits.

David:

Yes, that was the kind of thing that we worked on. To my regret I had a part in proposing wife's benefits, which has turned out to be a terrific part of the trouble with the program.

Q: Why did you regret it?

David:

The idea to begin with was that if this wage earner had a wife then he needed more benefits to support himself and his wife. This was a social insurance plan. So if you don't have a wife, you don't get it. If you do have a wife, you get this additional benefit.

Now that led to people raised holy hell. When they say, "Hey, that woman who sits at home and doesn't work gets the same benefit I do and I paid contributions." It's very hard to explain.

Q: But in the world of 1939, that fit completely with the kind of traditional families that we had in 1939. It wasn't until the 1960's or 1970's women entered the workforce and families changed, right?

David:

Yes, that's right.

Q: So it seems to me that you did it perfectly back in 1939, except that you didn't foresee the future!

David:

It turned out bad. Really we should have seen it coming. Women entered the labor force in a big way during World War II and it was already coming along in the 1939 era.

Q: This is a very interesting question, so let me ask it in a very pointed way. In 1939 when you designed wife's benefits, did you guys consider that this might be a problem down the road when women entered the workforce?

David:

No we did not. We did not foresee it.

The other thing of course was widow's benefits, we didn't have much trouble with that. But children's benefits had a lot of stumbling blocks. There were problems about who was a child, how to establish that someone was the wage-earner's child, and all that. But at any rate, that's the kind of thing we worked on.

Q: So at this time you're in the Analysis Division. I don't remember what it was called then.

David:

It was called the Analysis Division.

Q: Then there wasn't much that happened after the 1939 Amendments until probably the 1950 Amendments. There was not a lot of legislative change in the next 10 years.

David:

Probably the only thing was the contribution rate increase which was scheduled by law to start picking up in 1940 or 1941 or thereabouts. Congress quickly said: "We don't need this." They postponed it.

Q: Was there a lot of controversy over that at the time? Did people in the program think that was a serious problem?

David:

They thought it was not a good way to do, but the momentum was high. There was very little chance of stopping it. This was a wartime situation, although we were not in the War yet, but there were little pressure groups in terms of postponing the tax rate schedule. So we went on during the 1940's and the only big development was the coverage for military service--there was a lot of back and forth about that.

Q: In terms of your own career, what happened during the 1940's? You spent the rest of your career basically in the Analysis Division and successor organizations, right?

David:

Yes, except that after working in the section in the Analysis Division which was concerned with program planning, I became Assistant to the Division Director, Merrill Murray.

Q: Would this have been in the early 1940's?

David:

Early 1940's. At one point, I became Chief of the branch that worked on program planning, it was called the Program Planning Branch or something like that. In other words, I was not his Assistant anymore, I was the Branch Chief

Q: What was the Analysis Division doing in the 1940's? How were you keeping busy?

David:

We had what we called the "developmental program," which was the brain-child of John Corson. We prepared scads of black books on what should be done with insured status, what should be done with calculating the average wage, and what should be done about the dependents and survivors benefits. We had probably a dozen or so books and we kept improving them.

Q: I imagine a lot of it ended up paying off later on with the 1950 Amendments. For that period you were sort of doing the analytical ground work, right?

David:

Yes, the analytical ground work.

I went into the Army in 1943. Then when I came out, I came out as a Branch Chief--whatever the term was--it was probably Branch. It was in the late 1940's.

So I had my hand in the military service coverage issue and all this developmental program work.

Now, going into the late 1940's, Bob Ball came to Baltimore for a job interview at Central Office. He had been an employee at a District Office. He came to be interviewed here at Central Office, and he came to my desk. I remember reporting to my superiors, here was a world-beater, here was a ball of fire, and we should grab him as fast as we can.

Q: You turned out to be right!

David:

It was so easy to see. He was head and shoulders above everyone else. Even though he did not know anything about what was going on in our neck of the woods, he was just so smart and so good.

Then in the late 1940's he was offered a job with the American Council on Education, and he and I did a lot of soul searching. I lived with the Ball's at that time, my wife and I did, after I came out of the Army. Bob and I would drive back and forth from Baltimore to where the Balls lived in Annapolis. We lived there for quite a few weeks while we were hunting for a place. So we had these long talks about whether he should take it or not, and then it was clear he should.

So Ball was out of Social Security at the time of the 1948 Advisory Council. He came back for the 1948 Advisory Council. When the Advisory Council was finished, he came back to the Bureau.

Q: Right. After the Advisory Council, he came back to SSA and the Bureau somewhere.

David:

Then the question was: "What to do about Alvin?" Alvin was made Assistant to the Bureau Director, Oscar Pogge, so that there was a place to put Bob Ball.

Q: I've gotten confused here. So they moved you to become Oscar Pogge's Assistant and put Ball in your old job in Policy Analysis?

David:

I think that's right.

So Bob was not in Social Security at the time of the 1949 Committee Report. The legislation was passed in 1950. In 1949 all the work with the Ways and Means Committee was done. He was not in on that except insofar as he and I exchanged information, which we did quite a lot. So he had a hand in it through me.

Q: What were you guys doing for the 1948-1949 Advisory Council in the Policy Analysis Group? Were you doing something different similar to what you did with the 1939 Group?

David:

Yes.

Q: Were you doing studies, reports and analysis when they would ask you: "What would happen if we did this?" And you'd write a paper according to their request.

David:

Yes, except it was more a self-starting on our part. They didn't even ask for it. We offered. I spent many, many hours in the Committee offices working on these issues. There was a long, long period of time in which I commuted nearly every day to Washington.

Q:

Now, one thing that I'm curious about is that up to now your career was in policy analysis. Then you went into the job of Assistant Bureau Director. That's more of an operational job I would think. Or is that how you did it?

David:

It was more of an operational job, but still I was not a line officer. I was an assistant to the Director, and I got into everything that he got into.

Q:

So you were doing analysis for the Bureau Director, in effect?

David:

Yes.

I had a close operation with relationship with Bob Ball. So that worked out quite well. It started with the fact that we were friends back to 1939-1940, not just in terms of my career.

Q: May I say a couple of things before you go onto the next step?

David:

Yes.

Q: One of the things that interests me is the role of the policy component at SSA in terms of how important it was institutionally. In recent years the policy component has not been very important at SSA, in my opinion. It seems to me in those early years, in the 1940's, 1950's and 1960's it was very important. The policy component was a major player. Is that a correct impression?

David:

Yes, that's correct.

Q: So that's another question I wanted to ask you. So now when Ball comes back to the agency and you shift over to the Bureau and he takes the job in Policy Analysis, it sounds to me that in effect you are both doing similar kinds of work. You're doing policy analysis in the Bureau Director's office and that you guys are kind of a team.

David:

Yes.

After the 1952 election Eisenhower came into office and Oscar Pogge resigned. At around that time the Ways and Means Committee had a subcommittee and Burr Harrison of Virginia was its Chairman. He was a Chamber of Commerce man. He was a fierce opponent of Social Security and it looked as though the new Administration was going to clean house. The Bureau was run by a bunch of "hold-overs" and that's when Oscar felt he had no chance and he got out. Bob became Acting Director of the Bureau for a time and then they brought in Victor Christgau as Bureau Director and Bob was his Deputy.

That was around 1954. Bob as Assistant was still not going to be secure until one high point in 1954 when the Department came to Social Security for a meeting. I don't know whether your material includes this, but in early 1954 there was a big meeting in the auditorium. The meeting with the Department included all our Payment Center chiefs and a large number of District Office managers, maybe all of them, and all of the top staff at Central Office. I don't know how many that came to. The auditorium was full. I would guess over a thousand.

So just one District Office manager was called to make a statement, as a representative of the managers. The District Office managers were accustomed to reporting to their Regional Representatives and they knew what the story was. They did a creditable job. Not so the Payment Center chiefs who did not seem to have the same ongoing relationship with their superiors. So one of them was called on and it was terrible. He had a piece of paper in front of him and he just read from it and it hardly made sense. Then they called in Bob Ball who was a natural. He had been doing this kind of thing for a long time. And he wowed them with things that were right up their alley. He talked about what was a good Republican position, what should be a good Republican position, on this insurance program. This is the way that we have greater efficiency in the economy, to stabilize the workforce. We do the job at low cost. It's the right Republican position because it encourages work, as compared to public assistance. He made the case that us Republicans should be for this kind of a program. It just was fantastic. We all wanted to be brought into that position. It was all set up for him. So that was one of the great historical high points.

Q: So that was kind of a turning point in shaping Secretary Hobby's attitude about the program? Is that what you're saying?

David:

Not kind of, it was.

Q: Okay.

David:

Not long after that, Bob received the Rockefeller Award. It was an award with dollars attached to it. This was in 1955 when he received the Department's Distinguished Service Award. So he and the rest of us were on the inside after that. That was the critical turning point. And absent Bob Ball, nobody could have done that. Had it not been for Ball changing the Administration's views on Social Security, it might have been the interests and forces that were focused on Burr Harrison and the Ways and means Committee that would have overcome Social Security. It could have really been taken apart. I can't overstate it; it was a major turning point.

Q: Now let me take you back to 1952 for a second; I want to talk a little bit about the coming in of the Eisenhower Administration and the departure of a lot of these long-time SSA officials, like Oscar Pogge and Altmeyer.

David:

Altmeyer was fired.

Q: And Oscar left. And Wilbur Cohen was reassigned to a different job; kind of demoted in some way. There seemed to have been a real change there.

David:

In 1953, they fired Altmeyer. And it was an especially brutal the way they did it.

Q: I think he was just a few months away from having full retirement benefits for his wife--spouse's benefits.

David:

That's right. That's what I meant by pretty brutal.

Q: Right.

David:

It was.

Q: How did the agency react when Altmeyer was fired? Was that a traumatic event for the institution? I would expect it to be. Or was it sort of expected?

David:

People didn't know enough about it. They did not know about the benefit burden. It really was carried out just a few months short and they could have done it. Well, they didn't do it.

But people like me at the low end and in the ranks didn't know about it. All we knew was that Altmeyer was fired. But we were not surprised. The circumstances we didn't find out about until later. It was early in 1953, soon after Hobby came in.

Q: There are a couple of people I'd like you to describe to me a little bit, or tell me any little anecdote about them that would give us a flavor of what their personality was or what sort of manager they were; what sort of colleague they were, to those of us who never had the opportunity to meet them. So I'm going to ask you about several people along the way.

But one of them is Altmeyer. Did you have many dealings with Altmeyer? Did you have much of an opportunity to see him in action? Tell me a little bit about him.

David:

I had plenty of opportunity. I would go to the Board meetings quite often. I attended many Board meetings, at some of which I made presentations on subjects that were current. I'm trying to think of how to say this. He was a dry personality.

I think of him as an efficient administrator, and not a colorful personality.

Wilbur Cohen was a colorful one.

Q: Okay, tell me about Wilbur. Those were two of the people I wanted you to tell me about, and contrast a little bit.

David:

Wilbur was a devoted supporter of Social Security. He was a natural for working with the Congressional Committees. I went to many Committee meetings with him, and meetings with individual members of Congress and the Senate. And he was especially good at establishing a relationship with them.

I could not understand how well it worked. I didn't think we were all that good. But it worked so well. In their office, they were buddies--Senators and members of Congress both. It was the way he was made. And he was the one who had vision and knew way ahead of the rest of us what should be done next, and what we should propose.

One of the things I remember about Wilbur is that I didn't think he could write very well. He was so good that one didn't think very much about it. But he was not so good writing, which I was especially sensitive to.

One of the things about Bob Ball was that he could write. People around him couldn't. Wilbur was not a good writer but he was awfully good orally, and he was devoted to the idea of Social Security. I come back to the idea of Social Security.

Q: Okay. Can you think of any stories or anything during those times you were attending those board meetings when Altmeyer was Chairman of the Board? Any particular anecdotes come back to you that would give me an idea about Altmeyer, the way he operated? If not, that's all right, we'll go on to something else.

David:

No, I can only remember that when I made a presentation, he was appreciative, and I was complimented.

Oh, I wrote something for him a couple of times. I forget what the occasions were. But I wrote to him, I think twice. And he thanked me. He made some remark about my papers being "literary." It was supposed to be a compliment. But I thought there was a little put-down in the comment because he was referring to the quality of the prose instead of what I said.

Q: Instead of the content. Because you were known for being a fine writer; I mean, it was one of your prides, I think, right?

David:

One of my prides, yes. I took pains, I worked hard. Bob used to say that it came out easily on the first draft. And I never could convince him that it was not true. You had to work at it. I worked hard.

That reminds me of the drafts of President Roosevelt's speeches in the archives at Hyde Park. The fifth draft of those speeches are almost unrecognizable compared to the first, it took many drafts to get it right. And that was about the way it was with me--the fifth draft was almost unrecognizable compared to the first.

Anyway, Wilbur Cohen was devoted to the program and he was a visionary; he awfully good at working directly with people.

Q: How about a couple of these other folks. well, Oscar Pogge? Tell me about working for Oscar when you were working for him briefly.

David:

He was just about an ideal boss. I would take a speech that somebody had written for him and fix it up. And he would like it.

One time, I remember, I corrected his pronunciation. I hated the fact that I had done it--it had come out before I knew what had happened. And I just felt so bad about having done it. But anyway, it didn't bother him.

I regarded him as an extremely competent administrator, along with John Corson. Oscar was a born administrator.

Q: In a real way, the head of the Bureau was the number two official in the organization.

David:

Yes, the Bureau Director ran the programs. He appeared before the appropriations committees. Bob Ball, for example, established an excellent relationship with the committees, the appropriations committees. Bob established an excellent relationship with the committees; he even sold them on Social Security too.

Q: How about Corson? You mentioned John Corson.

David:

Oh he was a fabulous guy. I well remember him.

Many times I remember I'd be driving past the Social Security building late at night-- I would be driving back on my way home from the theater or something like that--and the building was dark except the light in John Corson's office. There he would be, working late into the night.

He had a reading file. Every memorandum that we've done in the Bureau went to John's reading file. And he would read this file at night. Many times I would write a memorandum or something to someone else and the next morning I would get a comment of some kind from Corson about what I had written the day before.

Eventually I became his speech writer. What I remember about that is that is that he once said to me about a speech I did for him that it was the first time he had ever had a speech written for him in which he did not want to change even a comma.

Anyway, he was a terrific administrator too.

I remember one thing about him, one conversation. He said to me, "What I am after is to make this Bureau like the Swiss nation. I want to make it so strong that nobody will want to attack it." And we made it virtually impregnable, as much as that could be done at that level as directors.

Q: I guess that was the start of the reputation that the agency acquired for efficient administration; of being an effective organization. For many decades, we've had that reputation. And I think it started with John Corson.

David:

I think so too. He was just great--I can't think of a better word. He had full command of the material, and all that you wanted to know about the operation. And these were days when not much was happening except in operations; how long did it take to pay a claim, and error rates, and so on. He was in full command of all of it and it was an impressive thing to see.

Q: Let's pick back up with the 1954 period when Ball came back and you switched jobs. What happened when Ball was shifted into the job of Deputy Director to the Bureau and Vic Christgau came in? What happened to you? Where did you go in your career? Did you stay there in the Bureau?

David:

I went back to Program Analysis.

I wasn't sure that I was at home with all the new functions they had by this time. They really now had expanded duties. Their job included my old stomping ground of program planning, but it now also included statistics and industrial classification. We had a branch that was in charge of--I think it was called Industrial Classification--classification coding. It included all those things--a lot of things which I did not feel at home with.

Q: And did you become the Director of the Division of Program Analysis at that time?

David:

I was Director of the division that included not only program analysis; it included statistics, classification and coding and some kind of research branch.

Q: Now what did we call it then? Was it OPEP?

David:

OPEP was a later development; we were already out in Woodlawn then.

Anyway, somewhere in there, the Bureau of Old Age and Survivors Insurance was abolished.

Q: SSA was created in 1946.

David:

In June of 1946. And the Board went away and we got a Commissioner.

I remember the meeting at which Bob Ball stated: "The Bureau of Old Age and Survivors Insurance is abolished." And there was a gasp. It was then he brought out that we were then going to be the Social Security Administration.

He had many a discussion about what to call it. There was a choice between Administration or Social Security Service, and a couple of others. In retrospect, it seems easy that it came down to Social Security Administration.

That happened when were still down at the Equitable Building. When we moved to Woodlawn, we had already become the Social Security Administration.

Q: Now what did you do in this new job when you went back to this expanded Program Analysis group? What was your role there?

David:

I was Director of it.

Q: Let's talk about some of the things that were happening. . .

David:

Let me straighten one thing out first. When we became the Social Security Administration, some of those things which I said I was not at home with, became Ida Merriman's territory--which I welcomed. I can't remember what year that was.

Q: Well, I can research that later. I'll find out.

David:

I became Assistant Director in charge of program planning; not including those things that I was not involved with like the statistics branch and classification and coding and the other pieces of it, some of which I don't now remember.

Q: All right. Let's pick up about 1954. the big thing that happened in 1954 was expanding the program to self-employed and to farmers.

David:

Yes. That had been the final result of all this work that we had been doing, all the details of it. Like how did you manage to apply the retirement test? How did you work that with the self-employed. There were lots of issues that needed to be worked on, to make them fit between the old system and the new system. In the original system you had an employer-employee relationship, and now we had the self-employed. For example, what should be the contribution rate for the self-employed? Bringing in the retirement test and a whole bunch of details which we had worked on over the years in these developmental program reports.

In the meantime, we had an Advisory Council on Coverage, chaired by a long-time liaison, Reinhard Hohaus. Like the other Advisory Councils it had labor representatives, employer representatives and representatives of the public. Hohaus was chairman of that. And the Council came out with a unanimous report in support of extension of coverage.

People like me felt that was a key to the future of Social Security. It was brought in just for employees in commerce and industry, it wasn't going to go anywhere. If there was going to be this strict division between those who were covered and those who were not covered it would be a friction--the key to the future was extended coverage. Of course, I said that I saw it. Wilbur certainly saw it and Bob.

Q: You mentioned that when we put in the provisions for covering self-employed that created some policy issues; how do you decide what the contribution rate is, and how do you do a retirement test. Were there other options that we considered that were debated and that people were advocating that didn't get picked? Was there some idea about charging the self-employed only one-half of the payroll amount? Can you think of any other alternatives that were considered but not adopted as part of those discussions?

David:

We discussed all the possibilities, including the double employee tax, including the same tax as employees paid, or somewhere in between. To tell the truth, I don't remember how we finally looked at that.

But anyway, we explored all those in considerable length. And I gave a prize to George Liebowitz, who had done a lot of good work on making the retirement test adaptable or workable in this context, which was a difficulty.

Q: It sure was.

David:

I don't think it's ever been done completely; it can't be done.

Q: Oh, you know, when I was a Claims Rep, that was still one of our toughest imponderables, the questionable retirement test for the self-employed. Traditionally, it's a difficult area for us to administer.

I'm working on a paper about the history of the retirement test and how it evolved, and I am very interested in this subject. People who want to abolish the retirement test argue that the only reason that we have a retirement test was that in the 1930's we were trying to force older workers out of the labor force, and that's the reason we put it in. Is that true?

David:

I don't think so. The reason there was a retirement test is this is a program of insurance against loss of earnings. If you had no loss of earnings, the insurance does not apply. I mean, if your house didn't burn down, you didn't get paid. And that was a clear, simple idea; you were insuring against the loss of earnings due to retirement.

Q: So that was clearly the understanding that the Agency had about it during those years--that's the way we thought of it.

David:

That's the way we thought of it. And that's the way you thought of it in 1954 when you were struggling with how to cover the self-employed?

David:

I've been struggling with that question for more than that, and not just in 1954.

Q: Okay.

David:

1954 was when it happened.

Q: So for years you've been analyzing that question.

David:

Analyzing doesn't seem to be the right word; we were very concerned about it.

Q: But still in that context of the idea of insurance. That somehow the self-employed would have to be under that same principle; that there would have to be some kind of retirement test for them, some loss of earnings?

David:

Sure. Good. That's what I thought, but I wasn't sure. That was very helpful.

On the retirement test, it's been cut down, whittled down, more and more. And from the start, it's been unpopular as can be. Why can this man who has all this income from stocks and bonds and rent get his benefit and I can't? And that is awfully hard to explain. And the idea of insurance--people didn't pick it up. They didn't get it, and they still don't.

Q: I agree.

David:

I remember I made a presentation at the National Council on the Aging. They were all for abolishing the retirement test. I made a strong presentation, as good as you could do, and I lost.

Q: You couldn't persuade them?

David:

Ellen Winston, who was then the President of the National Council, came over to me afterwards and said she was awfully sorry, that it could not have been done better, but it was clear that these guys just were not going to buy it.

Q: Now I don't remember when exactly we put in the provision that people aged 70 and older no longer had to be subject to the retirement test.

David:

That came in very early. I just don't remember how it worked; I remember it was very early.

Q: Do you remember the discussion and the debate about that? Were you participating in that?

David:

I did participate. I thought that by age 70 there was not enough left of work to make it a problem. By that time, most of them had retired or lost their jobs. And so it was not a big deal to cancel the test at age 70. I didn't think we ever had trouble about that.

Q: But if you looked at it philosophically, in a sense it would be the first time we agreed to abandon that principle, right?

David:

Yeah. I'm a little bit uncomfortable about saying it that way.

Q: All right, say it your way. That was my way.

David:

I put more emphasis on the concept that by age 70, it was not a live issue anymore. There aren't a lot of people left. It isn't worth the trouble. We felt that most people had already retired anyway. And there were not enough left to make it worthwhile to administer. That's the way I felt about it. I didn't think that there's a breach; it's only 5 years. But it seemed to me that we would not have breached any principle.

Q: I think that you expressed the view that became the accepted view.

All right, let's go to the other thing that happened in 1954 that was of some interest. And that was the disability freeze became part of the law. Could you touch on that?

David:

Yes, of course.

We were as strong as we could be for disability benefits, going way back to the developmental program reports on disability benefits.

Our argument was, how could you deny retirement benefits on account of a period of disability which caused a lack of insured status? How could anyone possibly not support at least a freeze. Even if you're not going to support benefits for disability over and above the freeze, it hardly seems fair to have your benefits reduced when you're disabled. Or you could lose insured status altogether.

Nevertheless they opposed it as an "entering wedge"--they being the Republicans in Congress.)

Q: And the AMA?

David:

The AMA and everybody else. Including the National Association of Manufacturers. And they saw it, as I said, as an entering wedge.

In 1952 there was an attempt to do a freeze that never really took effect. I don't know exactly how it is that we got it into the law; Wilbur got it into the law. That law said you would have this freeze which would go into effect on July 1 and abolished in the month before it took effect. That seems comical now when I look back on that freeze that expired before it took place. That was brainchild of Wilbur's--to get it into the law, even though it stopped. It was strange. I could not see what great value it was. But Wilbur thought it was. And I 'm sure he was right.

So it took until 1956 to get benefits put into the law. And it was vigorously opposed by the Eisenhower Administration.

I remember doing draft letters to committees of why we were opposed to disability benefits. I got selected to send a letter the Finance Committee. I did as good as I could. Marian Folsom had asked me to do it. And what the hell; I got selected. If I didn't write, it, somebody else would. I felt some degree of pride. He had asked me to do it, and I did as good as I could. When Wilbur saw my letter, he hit the ceiling. He used foul language that I had never heard from him before. "You didn't need to do that," he complained. But I thought I did. And he did not like that.

Q: He was mad because you had done too good of a job, right?

David:

That's what he said. He said, "You didn't need to do that; you didn't need to write it that good." Well you know, the Administration made a case and I picked it up and ran with it as best I could.

Q: Even though you yourself personally didn't agree with it.

David:

I disagreed strongly.

That incident with Wilbur was in Leona McKennan's office. I felt unhappy that would lit into me like that. And more unhappy that he would use this foul language which I had never heard from him, in Leona's office.

Q: Was she there?

David:

Yes, she was there, oh yes. It wouldn't have mattered otherwise.

Q: So that's an example of how deeply Wilbur cared about this issue, and how much he wanted disability to come in. And the irony, of course, is that you both were in agreement with each other at that point; but you were doing your duty.

David:

Well, I was doing my duty. And my pride was at stake. You were asked to do it and I was trying to do it as well as I knew how. I wasn't the one to compromise on it--he asked me to do it, and I was going to do it.

Q: So you couldn't bring yourself to be a political manipulator by trying to manipulate this report to make it look like you were making the case but never really making it. You could never do that?

David:

No.

Then we did get it adopted in 1956. We got scads of letters from people addressed to the President, to Eisenhower, telling him how wonderful it was that he had given them these disability benefits. How much it meant to them. They went on at great lengths, and all addressed to Eisenhower, who had opposed it as strongly as he knew how.

Q: But I think that Marion Folsom was also sort of in the position that you were in, in that he was sympathetic to the idea of disability benefits. But he felt his orders were to make a case against it. Is that right?

David:

I think there is a good deal to that; that's my opinion. I don't think I could make a big argument about it. But I have that feeling. He was a pretty good guy. And I think that he would rather not hurt the opposition.

We did have different versions of the letter. And I remember he called one "this is the namby-pamby version."

Q: But he was like you; he thought your duty was to make the strongest case you could.

David:

Yes, except I don't know how strong he felt. I don't think it was as big an issue for him.

Q: As it was for Wilbur?

David:

As it was for me.

Q: But he clearly didn't want you to write a namby-pamby version.

David:

I wrote one. I think I wrote three different versions--one supporting the benefits, and one opposing them, and one namby-pamby.

Q: Okay. So disability came in. So what's next?

David:

I can remember when we were arguing about it. The big issue was that the cost would be out of control. This is what the disability insurance industry argued. We had terrible trouble with that; the costs went up and up and up. We were worried that the courts would take it out by hands and so we couldn't control the costs.

So I said, "For goodness sakes, let's don't worry about that. We figure that our best estimate is that it's going to cost half a percent of payroll for disability benefits. Suppose we are way off, 100 percent off, maybe it will cost 1 percent. So what." That's what we argued about.

In later years, it turned out to be true; the courts beat us down over and over. And it cost way the hell and gone over 1 percent.

Q: But on the other hand, there are millions of people who benefit from those benefits, or who benefitted for decades.

David:

That's right.

Q: So the need that benefit addresses was there. But it was an unmet need for a long, long time. So you guys did well; you should have no regrets. You did well for the Nation.

David:

That's true.

Q: So after disability was finished, what did you guys turn your attention to?

David:

I guess the big thing that comes to mind . . .

Q: Oh, I forgot about the Advisory Council. You were the Staff Director for the 1958 Advisory Council--and then several more after that. Was that the thing you wanted to talk about? Or did you have something else?

David:

I should mention that we spent considerable time and effort on benefit levels in that interval.

I consider a major turning point as the 1972 Amendments. Because that year you got a 20 percent increase in benefits, in one fell swoop. You had a 20 percent increase due to Bob Ball, because he sold Wilbur Mills. He told Mills we could afford it; it was workable; it was do-able; and if you want to be President, Mr. Mills, this is a good way to start out. And Wilbur Mills picked that up and used his great influence in Congress to move it through.

So there was a 20 percent increase, together with the provision for automatic COLA's in the future.

Q: Which was very important.

David:

Without COLAs the program would not be where it is today.

Q: Absolutely.

Well, let's come back and pick that up a little bit later; you're jumping ahead to the end of your story and your career's end. Let's go back to 1958 and your service on the 1958 Advisory Council. Can you tell me what that was and what you did?

David:

I did what the Staff Director should do. After reading, I would write down what the Council was driving at and the text of the report on a given issue, and mail it out to them. And sometimes talk with them on the telephone about it. And in the end, I would get them individually to sign off on that version of our report.

Q: Well, that report ended up becoming the 1960 Amendments. That's what led to the 1960 Amendments. I'm trying to remember what happened in the 1960 Amendments. It wasn't all that much. Early retirement for men, and some liberalizing of the retirement test and some liberalizing of the benefit-payment requirements.

David:

Insured status.

My Advisory Council was disability.

Q: I don't know; I had that the 1958 Advisory Council was your first one. And then the 1965, then the 1968, then the 1971. But I had you down for doing four of them.

Well, let me put it to you this way. The next big thing that we're going to talk about is Medicare in 1965. So after disability in 1956, and before Medicare in 1965, was there anything else important that you can think of in between that period? Or is Medicare the next big topic for us?

David:

As best I can recall, there was no other big division after disability and Medicare.

There were a number of benefit increases; none as big as 20 percent. But there were I think 3 benefit increases in that interval, and minor improvements in eligibility for disability benefits. I think we liberalized the insured-status requirement for disability. We got something like it was expected to endure for at least 6 months or until death. We liberalized it.

Q: Right.

David:

And that sounds to me like 1958.

Q: Yeah, I think that might be right.

David:

My recollection is that what I considered my Advisory Council had to do with disability. I remember who was one it. We had Henry Kessler, one of the great re-hab men. He would not have been on any other Advisory Council other than one having to do with disability.

Q: Well then, let's talk about Medicare a little bit; about the run-up to Medicare and the development of the 1965 law, which was a big watershed-the next great big, important event. I presume that again, you had either done this analysis in your program-development books or you did it again during this period all over?

David:

We'd been doing it for many years. We'd actually had books prepared that we could use to pass a bill as far back as the late 1950's.

But anyway, we had abortive tries in 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963. It wasn't until the Johnson landslide in 1964 that there was enough votes on the Ways and Means and the Finance Committees to get it passed.

With the Johnson landslide, membership of the Ways and Means expanded. The new Congress included a sizeable increase in the Democratic vote. And it passed easily in the House and the Senate. Over all these years when we'd been trying, and some votes were successful as a matter of fact, solidly the South voted against us. All Southern Democrats voted against us, which at the time seemed strange. It was against their best interests, but they were conservatives.

Q: Now the big breakthrough in 1965 that sort of pushed it over and let it be enacted was this strategy that I think Wilbur Cohen and others came up with of just covering the elderly--just covering the Social Security retirees, and not having a health-insurance program that covered everybody in the Nation. Before that, there was a lot of talk and interest in having a universal health-care program.

David:

Way back to Oscar Ewing, and even before, way back to the early 1940's.

I remember Watson Miller was the FSA administrator and President Truman decided he was going to push it in getting himself reelected in 1948. He was going to push for medicare--it was not called Medicare.

Q: It was called national health insurance; what he had in mind.

David:

National health insurance, right. And he was going to get this done and he had not really anticipated the hale of opposition; everybody in the insurance industry; all the doctors; all the insurance companies. They carried out a vicious campaign, which incidentally, is like the vicious campaign they carried on with the Clinton health care proposal--the Harry and Louise commercials. So Truman moved Ewing into that spot and his instructions were to get this done. And he was going to put Truman on the map in this area.

Q: So he was pushing it.

David:

Yes. Truman was. My understanding at the time was that he pushed Miller out because Miller was not able to do this kind of thing that Ewing was.

Q: Ewing was talking about covering the elderly. I can see in my mind the video clip of him making a speech about that.

David:

Summarily left behind the national idea.

Q: Now internally in SSA, in the analysis that we were doing on this issue of health insurance, were we proposing national health insurance? Did we have this idea that it would be a comprehensive thing that would cover everybody? Do you recall?

David:

I recall that, like Wilbur, I was in favor of everything we could get. If it was a half loaf, that was it.

Q: Were there any particular policy challenges that you guys had to face back in 1965 when it was becoming a reality? Where there issues that were associated with Medicare that required some policy decisions and policy analysis? When we, for example, did self-employed, we had to figure out how to make a retirement test for the self-employed. Was there anything like that with Medicare that you worked on?

David:

It must have been a lot, because I remember so many meetings that we went to-- including meetings with Clint Anderson and Amie Forand. And we had lots of issues to talk about.

Q: Okay.

Well, let's talk for a minute about administratively what was going on in SSA during this time. In the early 1960's, Bob Ball became Commissioner when Kennedy came in.

David:

Wilbur at that point became an Assistant Secretary.

Q: And Bob Ball was now the Commissioner of SSA. And you are still in the job as the head of the Policy Analysis Group which, I don't know, if it is called OPEP yet.

David:

Yes, somewhere about in there, I decided to call it that. Nobody challenged it.

There was a program planning group in the Department, an Assistant Secretary for Program Planning. And the suggestion was call it the Office of Program Planning. And I said, ""I'm going to have none of that, I'm going to put an E in there--Program Evaluation and Planning - Office of Program Evaluation and Planning." And that was when we were moving into the new building.

I will give you another little historical bit that comes to mind, at this point. And that is the meeting with Kennedy at which the new program got its name. I did not attend that meeting but I know about it. All kinds of suggestions were made, including Medicare. And somebody said, "You can't use Medicare, because there already is a program in existence called Medicare--an obscure program involving dependents of men in the armed forces--a small obscure program." And somebody said, "You can't use medicare because it's already in existence." And Kennedy overruled all the objections. He said, "We'll go with Medicare, period." And I thought that was strange to hear. I would not have thought to do that, but he did.

Q: Let me ask you about another institutional question. You had mentioned before that at one point, you had spun off some of these research things to Ida Merriam.

David:

They were spun off for me, and I was glad to spin them off.

Q: You were glad to spin them off, because it wasn't your area and it was Ida Merriam's area. But that became the Office of Research and Statistics. So at some point along this way--I don't know if it was called something else before that, now it is called the Office of Research and Statistics.

David:

I think it was called Research and Statistics.

Q: Okay. During a lot of this period, it seems to me, there were two important organizations: one was the Office of Program Evaluation and Planning, and the other was the Office of Research and Statistics, both of whom, to some degree, were doing policy analysis. I wonder if you could just describe to me a little bit what the respective roles were in those organizations and how they worked together.

David:

My feeling is that we had little to do in the way of working together.

Q: Okay.

David:

I'm not a natural relater--I was not a natural one to work with Ida. Somehow or other, we did not hit it off.

Q: Why? What was that about? Personality compatibility or what?

David:

I don't know. There was a kind of a rivalry. But I can't remember exactly, only that I had such good relationships with everybody else around, but not with Ida.

Q: Well, what I'm really getting at with this question is was there any rivalry between these two organizations to be the organization that was going to drive policy? Was there any kind of rivalry like that?

David:

There was not.

Q: There was not; okay. When Bob Ball became Commissioner, did that change the role that OPEP had? Did it change your role at all?

David:

Not at all.

Q: Okay. After medicare, what did you take up next? Before we get to 1972 and the important things that happened in 1972, was there anything else between 1965 and 1972 that you want to bring up? I can't thing of anything.

David:

I can't think of anything either.

Q: All right. Well, let's talk just a little bit briefly about the 1972 Amendments. And you've already mentioned the two key things in the 1972 Amendments--at least two of the three. One was the COLA's. So I want you to talk a little bit about the COLA-- the automatic COLA--what the issue was about automatic COLA's and why we wanted to go to automatic.

David:

And why all the others did not want to.

Q: Yes please. Talk a little bit about that.

David:

The argument was made by members of the Advisory Council, including one who had been Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under Nixon. He said, "If you put in automatic increases, then you'll dull the edge of the beneficiaries for trying to control inflation. If inflation isn't going to matter to them, they wouldn't be opposed to trying to produce inflation--they wouldn't worry about it." And he said,"that would be a deadly failure if those people are no longer worried about inflation and policies which resulted in inflation." He was a former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers.

Q: So was he opposed to COLA's?

David:

Very strongly.

There was no question about our position, we were for doing it. There was a question about whether Nixon was going to go along with it. And we worried hard about that. One of the things for which I will have to forever give credit to Nixon was whatever his reasons were, he said "I'm going to sing the bill." And of course he did.

We had large sessions with members of his staff--back and forth about that. And I don't know what was the final stage was. We really never could tell from our discussions what his staff wanted. And one day, we found out that he was going to sign it. I guess it had something to do with the 1972 election.

Q: Yeah, it did.

Now you said that we at SSA were strongly in favor of the automatic COLA's. Why? What was our position? Why did we think it was a good idea?

David:

Obviously, this was a ready way to keep the benefits doing what they should be doing. If we didn't have this, they'd gradually reduce their effect.

Q: So you were concerned about preserving the beneficiary's purchasing power; the value of their benefits.

David:

Yes.

Q: Okay.

Wasn't another argument being made around the COLA'S. Because Congress granted COLA's occasionally, whenever they passed a law to grant them, that tended to happen in election years, and people tended to bid-up the amount of the benefit, and it became a political question, rather than a technical question. So the question became not "How much did inflation increase" but "How much should we bid-up benefits?" And people thought that was a bad incentive for the political process to control the amount of the COLA. Was that an argument that was made, or was that a rationale given after the fact?

David:

After the fact. At the time that the process was going on, I never saw any sign that there was a political element in it. You couldn't see that in the committees--in Ways and Means and Finance.

I remember arguing at the time that this was not taking place in an election year-- at least it wasn't taking place in a presidential election year. The amendments in 1950 were not a presidential election year

Q: The big one was in 1950, when benefits went up 77 percent.

David:

Yes, that was not a presidential election. When they voted it out of Ways and Means, it was 1949. That was the big one relating to coverage. It was not an election year for the Senate Finance Committee, any more than any other even-numbered year would be.

I felt at the time that the case could well be made that benefit increases were not truly connected with election politics. I argued that an argument could be made on the other side. It was not working that way in fact.

Q: Okay. Now the other thing that you already mentioned about the 1972 Amendments was the 20 percent benefit increase that took place that year. And I think you've already talked about Wilbur Mills was persuaded to do that because he though it would help him in his ambition to be President.

David:

Bob Ball is the one who did it.

Q: That was another big feature of the 1972 Amendments.

David:

There was another thing about that. John Ehrlichman is reported to have said, after the 1972 Amendments, that Bob Ball could have stopped this from happening with his little finger if he wanted to. And that was absolutely true. But it turned out that after the 1972 election, Bob Ball resigned.

Q: I'm not sure that I understood that Ehrlichman remark. Could have stopped what with his little finger?

David:

He could have stopped the 20 percent increase.

Q: Oh.

David:

It all depends if he wanted to. But he didn't want to.

Q: So before the 1972 election, Ball was a very powerful, still a very politically powerful figure. And then after the 1972 election, I guess Nixon felt comfortable with letting him resign.

David:

Oh yes, sure. He didn't want to do it before the election. But he did want to do it. Regardless of how they sounded here in our own halls, we knew very well how they operated, we could hear that from the Republicans we knew. They didn't want to do it before the election and they were ready to do it right after the election.

Q: The other thing that happened in 1972, of course, was the SSI program. Did you have any involvement with that analysis in the development of the SSI proposals?

David:

Very, very little. A little of it comes to my mind.

I hated the idea of calling it "Supplemental Security Income." I thought that was terrible. But that was what Russell Long wanted to do.

Q: SSA was not real receptive to the coming of SSI, it seems to me. We would have preferred to keep our traditional program and we didn't want to get involved with SSI. Is that true?

David:

Yes. But we still had this great reputation for being able to administer something. And we were faced with the proposition "Who the hell else would you want to do it?" And there wasn't anybody. It just was a matter of setting up a new bureaucracy. It would be a large bite of trouble to start a new agency to handle this. It was big enough trouble as it was.

Q: Okay. So after the 1972 election, Bob Ball was encouraged I guess to resign?

David:

He didn't ever like to say he was fired. And he resigned in time.

Q: Then shortly thereafter in 1973, you left and some other people left. You retired in June of 1973.

David:

Yes.

Q: Was the choosing of the time for you to retire, was that related to the fact that Ball was leaving and other people were leaving? Or why did you decide to leave at that point? I mean, several people left then in 1973: you left; Ball left; Jack Futterman left.

David:

Jack Futterman left a year earlier.

Q: Okay.

David:

One reason I left was the civil service COLA. If I didn't leave, I'd lose the step increase. Financially, it figured out better to retire than have another cost of living increase.

Q: Okay.

David:

But I was uncomfortable. It was not a comfortable time. We did not have a Commissioner. As far as Arthur was concerned, that was fine.

Q: Art Hess?

David:

Yes. We got along famously. But he was only Acting. And I couldn't see where things were going to happen that where I would feel, as I say, comfortable about my participation.

I guess I had a feeling that after so many years not wanting to be insecure about my position. Not that I was insecure about losing my job. But I didn't see how things were going to be going on which I would especially want to be working on. My feeling was that I was not going to be finding things to do that I wanted to do and felt that I could do well. At that time, I was 67. It seemed like the time. And supported by the idea that financially, I was going to be better off, which turned out to be true.

Q: Was it hard for you, was it hard for you to leave?

David:

Yes and no. Mostly it was not hard.

I enjoyed retirement. I wrote letters in the first 5 years after I retired, saying how wonderful it was. And I do not have any regrets.

I miss the people, but not all that much.

We have touched upon the major historical points: the move to average benefits instead of cumulative; coverage of the self-employed; to a lesser extent, coverage of agricultural workers; the disability program; Medicare; and the 1972 benefit increases.

We talked about the big turning point in 1954, when Bob Ball stood up and made that wonderful speech. I think the program would have been irretrievably changed if the Republicans had gone the way it looked like they were going to go. It looked so clear to Oscar Pogge that he resigned. And at that time, I hunted up some people that had gone into commercial or industrial aspects of psychology. I had a degree in psychology. I didn't end up with any of them.

Q: So you were considering you might have to leave too?

David:

If the things had turned out the wrong way, I would be the first in line to get his head chopped off--the first one after bob Ball.

Q: Because you were the policy guy, and that's the sensitive area politically.

David:

Right.

Q: Well, we'll make this the last question. Just tell me how you enjoyed your career at Social Security. Were you glad you did it? Do you feel a sense of satisfaction from it? Just sum it up for me.

David:

I was very glad I did it, and I feel a lot satisfaction. This was a way to make what seemed to me, and still does, a valuable contribution to the welfare of the Nation. It was a way to make a contribution that was not difficult. Some people have to make their contribution and whichever way they turn they are damned--like Janet Reno.

I was never position of making a contribution at any cost to me in the way of soul searching, or of being in the middle where I was going to be criticized whichever way I turned. I never was in that spot.

Nor was I ever in a relationship with any of my colleagues which was other than satisfying. I mean, I spoke of Arthur and I always felt that we got along extremely well. And I thought that was the same with everybody: Hugh McKenna, Joe Fey, and everybody. The Administrative Law Judge, Jim McElvain, and everybody I got along well with. And everybody I liked; I got along well with. It seemed strange that it could be but it was. Everybody except Ida. And there never we had anything out and out unpleasant. We just did not hit it off.

Q: Well, I know many of those people speak very warmly of you. Many of them have told me what a gentleman, a gentle soul you are, that's how Jack Futterman described you.

David:

Yeah, I loved Jack.

Q: All right. I think we're done. Thanks.

|

| Alvin David at his home in Chicago, Illinois during his oral history interview, 10/20/97. SSA History Archives. |