Public Pension Statements in Selected Countries: A Comparison

Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 76 No. 1, 2016 (released February 2016)

Increases in longevity, changes in pension structure, and the shift to greater individual responsibility for retirement saving make it important for governments to provide workers with information about their public retirement benefits. Public pension statements are one way governments can do this. In this article, we compare public pension statements in Canada, Sweden, and the United States. For each of those countries, we briefly describe the public pension program and discuss the origins and content of the public pension statement. We conclude with an assessment of the information provided in the three countries' respective public pension statements.

Barbara Kritzer is lead analyst with the Office of Economic Analysis and Comparative Studies, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, Office of Retirement and Disability Policy (ORDP), Social Security Administration (SSA). Barbara Smith is a senior economist with the Office of Policy Research, Office of Retirement Policy, ORDP, SSA.

Acknowledgments: We are indebted to Arne Paulsson of the Swedish Pension Agency and to Gregg Zentner, Valérie Paré-Eberley, and their staff at Service Canada for providing a wealth of information on their countries' public pension statements. In addition, we thank John Jankowski, Ken Mannella, and Annika Súnden for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Contents of this publication are not copyrighted; any items may be reprinted, but citation of the Social Security Bulletin as the source is requested. The findings and conclusions presented in the Bulletin are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Social Security Administration.

Introduction

| CPP | Canada Pension Plan |

| FRA | full retirement age |

| FY | fiscal year |

| NDC | notional defined contribution [Sweden] |

| SOC | Statement of Contributions [Canada] |

| SPA | Swedish Pension Agency |

| SSA | Social Security Administration |

Retirement income security has become an important concern for workers in countries around the world. More responsibility for retirement saving is being placed on individual workers as governments make changes to their public pension systems—such as reducing benefit levels and increasing the retirement age—in response to the rapid aging of the population and employers shift from defined benefit to defined contribution plans. In most countries, life expectancy is increasing, with people spending more years in retirement. A longer retirement requires greater savings and resources to pay for the extra consumption and health-care costs of these additional years.

With the increases in longevity and the changes in pension structure, it is important that governments provide workers with information about their public retirement benefits and any changes to the programs that would affect those benefits. Public pension programs provide the foundation for retirement income for many workers, so it is essential that those workers know how much they will receive.

Public pension statements are one way countries can provide workers with information about their retirement programs. These statements contain an individual's earnings record and past contributions as well as estimates of future retirement benefits. Statements may also contain information about future changes to the programs.

In this article, we compare public pension statements in three countries: Canada, Sweden, and the United States. For each country, we discuss the origin of the public pension statement, its contents, how often it is mailed out, to which population groups it is sent, and how its effectiveness is evaluated.

In the first section, we present brief descriptions of the retirement income systems in each of the three countries. Next, we provide a comparison of the public pension statements in each country, followed by detailed descriptions of those statements. Finally, we assess the content of the three countries' public pension statements and discuss the role of evaluating the effectiveness of those statements.

Description of the Public Pension Systems in Canada, Sweden, and the United States

In this section, we focus on the public pension part of the retirement income systems in the three countries under study and provide some information on the other components of those systems.1

Canada

Canada's retirement income system consists of (1) the Old-Age Security (OAS) program, which provides a universal benefit;2,3 (2) the Canada Pension Plan (CPP), which provides an earnings-related benefit; (3) employer-provided registered pension plans; (4) individual savings options, such as personal registered retirement savings plans; and (5) tax-free savings accounts. The CPP covers all of Canada except the province of Quebec, which has a parallel plan—the Quebec Pension Plan (QPP)—with similar contribution and benefit provisions.

The CPP provides an earnings-related old-age pension at age 65. The employee and the employer each contribute 4.95 percent of the employee's earnings a month; in 2016, the maximum annual earnings used to calculate contributions are $54,900. Pensioners receive a reduced benefit from ages 60 to 64. Workers who remain in the labor force after age 65 (and do not claim a benefit) receive an 8.4 percent increase in benefits for every subsequent year of work up to age 70. In addition, workers may collect a CPP retirement pension and continue working. Beginning in 2012, CPP retirees who work must continue contributing from ages 60 to 64 and may choose to contribute from ages 65 to 70. (Previously, once individuals began receiving an old-age benefit, they could continue working but would have to stop contributing.) These additional contributions finance the Post-Retirement Benefit (PRB), which is paid when the individual fully retires. (The retiree receives a combined benefit when he or she stops working.) Earnings-related old-age benefits are adjusted quarterly according to changes in the consumer price index.

The CPP and QPP have the following special measures:

- a general drop-out provision that allows periods of low or no earnings to be excluded from the CPP/QPP benefit calculation;

- a child-rearing provision that covers parents who stopped working or received lower earnings in order to raise their children up to age 7; and

- a pension-sharing provision that allows spouses and common-law partners to share pension benefits.

A CPP survivor benefit is paid to a widow(er) or common-law partner (same sex or opposite sex) and children younger than age 18 (age 25 if a student). A surviving spouse younger than age 35 who does not have dependent children or a disability is not eligible for benefits. The deceased worker must have contributed during the lesser of 10 years or one-third of the years in which contributions could have been made; the minimum contribution period is 3 years. An income-tested OAS survivor benefit is paid to low-income widow(er)s aged 60–64 who are residents of Canada and have resided in the country for at least 10 years after reaching age 18.

Sweden

Sweden's retirement income system consists of (1) the two-pillar national pension (the notional defined contribution [NDC] and the mandatory individual account [premium pension]),4,5 (2) occupational pensions, and (3) personal pensions.

In 1999, Sweden introduced the national pension for workers born after 1954. There is a gradual transition from the old earnings-related social insurance system to the NDC and the premium pension system for persons born between 1938 and 1953.

The NDC scheme provides an earnings-related benefit that represents the largest share of retirement income. The NDC is a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) program in which a worker and employer contribute a combined 16 percent of that worker's earnings each month to his or her “hypothetical account,” which contains all contributions made during that individual's working life plus “interest.” The annual notional interest rate is equal to the growth of average earnings. Benefits are adjusted annually according to changes in wages.

Credit is given for periods of time when workers were receiving some social insurance benefits (such as unemployment), years they spent at home taking care of children, and time they spent in active military service and in pursuing higher education. The NDC scheme provides a flexible retirement age—as early as age 61—and incentives to work longer. The NDC pension is calculated by dividing the amount credited to a worker's account by the average life expectancy of that worker's cohort at the time of retirement. This means that as life expectancy rises, younger workers will need to work longer for a comparable benefit.

An automatic-balancing mechanism is applied if the system is in imbalance (liabilities are greater than assets). If that happens, both the notional interest rate and the indexation of current benefits are reduced temporarily to bring the system back into balance (Sundén 2009).

The premium pension scheme, on the other hand, is provided through privately managed individual retirement accounts, funded by combined employer and employee monthly contributions of 2.5 percent of earnings. Accountholders may choose up to five investment funds at a time and may switch from one fund to another. Those who do not make a choice are assigned to a default fund. At retirement, a worker may choose between a fixed or variable annuity. A voluntary survivor benefit is also available. The retirement age is the same as that for the NDC: flexible, beginning at age 61.

The NDC scheme does not provide a survivor benefit to the deceased worker's survivors. (Under that scheme, when an insured person dies before reaching the retirement age, his or her NDC account balance is distributed to the accounts of his or her birth cohort.) A survivor benefit is paid to the deceased worker's surviving spouse or partner under the premium pension scheme if the insured person elected coverage for that benefit.

United States

The U.S. retirement income system consists of (1) Social Security;6 (2) employer-provided pensions and retirement savings plans; and (3) individual savings options, such as individual retirement accounts and personal retirement savings.

Social Security benefits are based on the average of the worker's 35 highest years of earnings. The earnings are adjusted for increases in the national average wage prior to age 60. Both the employee and the employer contribute 6.2 percent of the employee's earnings a month; the maximum annual earnings used to calculate contributions are $118,500 in 2016. Full Social Security retirement benefits are paid to individuals at age 66 (gradually rising to age 67 by 2027) with at least 10 years of coverage (40 quarters).7 Quarters of coverage are based on the insured person's annual earnings. In 2016, the minimum amount of earnings to receive 1 quarter of coverage is $1,260. That amount is adjusted annually to reflect past increases in national average wages. Reduced benefits are paid to individuals who claim from age 62 to the full retirement age (FRA). Also, from age 62 to the FRA, if an individual works and receives a retirement benefit, that individual's benefit amount is subject to an earnings test. Claiming of Social Security benefits may be deferred until age 70. An 8 percent increase is paid for each year (up to age 70) an insured worker defers claiming benefits beyond the FRA.

A spousal benefit is paid to the spouse of an insured worker beginning at age 62 or at any age if the spouse is caring for a disabled child or a child younger than age 16 who must be receiving Social Security benefits on the worker's record. To be eligible, a divorced spouse must be currently unmarried and have been married for at least 10 years. A spouse is not eligible if he or she receives or is entitled to receive a higher Social Security benefit based on his or her own earnings record. The spouse's benefit is 50 percent of the insured worker's retirement benefit; the spouse's benefit is also reduced for individuals younger than the FRA.

A survivor benefit is paid if the deceased worker is insured; that is, if the worker has 40 quarters of coverage or if he or she is younger than age 42 and has a minimum of 6 quarters of coverage and total quarters equal to at least his or her age minus 21. Individuals eligible for survivor benefits include a widow(er) aged 60 or older who was married to the insured worker at least 9 months prior to his or her death and a surviving divorced spouse if the marriage lasted at least 10 years and the surviving spouse did not enter the marriage after attaining age 60 or has not remarried. A widow(er) or surviving divorced spouse is eligible at any age if he or she is caring for a child receiving benefits as a survivor on the worker's record and that child is younger than age 16 or disabled. Other individuals eligible for survivor benefits include a disabled widow(er) or surviving divorced spouse aged 50 or older with a disability that started before or within 7 years of the insured worker's death; an unmarried child younger than age 18 (age 19 if a full-time elementary or secondary student and no age limit if disabled before age 22); and a dependent parent aged 62 or older who has not remarried since the insured worker's death and who is at least 50 percent dependent on the deceased worker at the time of his or her death. These rules also apply to same-sex marriages. Note that Social Security benefits are adjusted annually according to changes in the cost of living.

Overview of Public Pension Statements in Canada, Sweden, and the United States

In this section, we describe the main features of the public pension statements in the three countries under study and highlight both the similarities and the differences between their respective statements. (See Appendices A, B, and C for sample statements from each of the three countries. For a comparison of public pension statements in selected European Union countries, refer to Appendix D.)

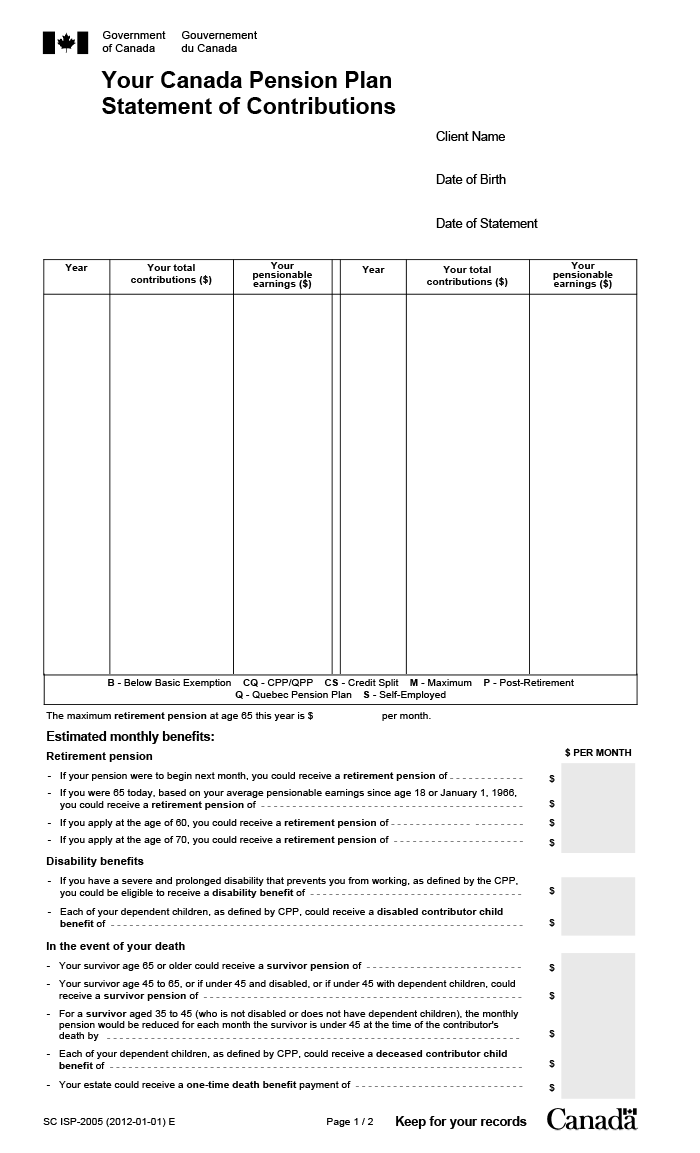

Canada: Statement of Contributions

Since the inception of the CPP in 1966, there has been a legislative requirement to send workers a Statement of Contributions (SOC)8 on request. In Canada, every person aged 18 or older who earns a wage or salary and has contributed to the CPP is eligible to receive an SOC. There is no requirement that CPP initiate such mailings.

Contents. For statement recipients aged 30 or older, the SOC includes information on their contributions, pensionable earnings, retirement pension (with the benefit receivable at age 65 listed before that receivable at age 60), disability benefit, survivor benefit (varies by age of the recipient), and the lump-sum benefit payable upon those individuals' death. For statement recipients aged 18–29, the SOC only includes information on their contributions and pensionable earnings, omitting information on the retirement pension, disability benefit, survivor benefit, and lump-sum death benefit.9

The SOC provides recipients with information on the amount of benefits they or their survivors can expect to receive in the event of retirement, disability, or death. The information on earnings enables recipients to validate the accuracy of the data and make any necessary changes. Since 1984, the CPP has been able to correct over 1 million worker accounts, with the majority of corrections concerning earnings.

Frequency. Although there is no legislative requirement to send out SOCs, the CPP began mailing them out in the mid-1980s because it noticed that very few were being requested. There is no pattern as to when the CPP mails SOCs to people of different ages. At times, the budget limits the number of SOCs that can be sent out; on other occasions, the number of SOCs to mail out comes directly from the Canadian Parliament. In addition, when any new pension legislation directly affects certain groups of workers, the CPP sends an SOC to those workers most affected by the new rules to provide them with information on any changes. Beginning in 2002, the CPP initiated “Smart SOC,” an approach that focused on mailing the public pension statement to new contributors to the plan; workers who were approaching retirement age (who, depending upon the year could be aged 50–54, 59–60, or 59–64); and workers who were eligible for a CPP retirement pension but had not yet applied. The last mass mailing of SOCs occurred in 2013. Since then, the CPP has been encouraging Canadians to access the online SOC or request that a printed version be mailed to them.10 The requested SOCs do not include inserts with information pertinent to different age groups (Service Canada staff, personal communication with the authors, September 11, 2015). Table 1 provides a chronological account of the SOC mailings from 1966 through the present.

| Time period | Development |

|---|---|

| 1966 | Canadian Pension Plan (CPP) was required by law to send the Statement of Contributions (SOC) to individuals upon request. |

| 1984 | CPP began proactive mailing to inform workers about their benefits because few workers were requesting the SOC.a |

| 1987 | Significant changes were made to Canada's pension legislation. Workers who received an SOC in the 1984–1986 period received an updated SOC. |

| After 1987 | SOCs were sent out every 4 or 5 years to eligible workers. |

| 1990s | SOCs were sent to younger workers with information regarding the security of their contributions, in response to media articles that the CPP was going broke. |

| 1997 | The Minister of Finance stated that SOCs should be sent out yearly when feasible. |

| 1999 | SOCs were sent to 3 million workers aged 18–28 and to 85,000 individuals aged 65 or older who were eligible for a CPP Old-Age Security pension. |

| 2000 | SOCs were sent to 10 million workers (included most age groups). |

| 2001 | SOCs were sent to all 13 million eligible workers (all age groups except the oldest) in accordance with the Minister of Finance's 1997 announcement. |

| After 2001 | Budget money for the SOC program targeted smaller mailings and the creation of an online SOC. The “Smart SOC” approach was adopted.b SOCs were mailed to new earners, workers nearing retirement age, and those eligible for a CPP Old-Age Security pension but had not applied. |

| 2005 | SOCs were made available online. SOC mailings to workers aged 55–64 included an insert promoting online services. Online applications increased from 2.5 percent to 25 percent of all retirement applications from 2005 through 2010. |

| 2010 | SOCs were sent to 1.3 million workers aged 59–70, along with a letter and an insert explaining the recent changes and how those workers might be affected. |

| 2012 | No SOCs were sent out because of budgetary reasons. |

| 2013 | The CPP conducted the last mass mailing of SOCs to new, young earners; workers aged 59-64; and those aged 70 or older who had not already applied for their CPP retirement pension. |

| 2014 to the present | Since 2013, Canadians have been encouraged to access online SOCs or request printed SOCs. |

| SOURCE: Gregg Zentner (personal communication with the authors via e-mails and internal memoranda from Service Canada, 2011–2013). | |

| a. From the late 1970s to the early 1980s, less than one-half of 1 percent of workers had actually requested an SOC. | |

| b. Under Smart SOC, Service Canada mailed statements to selected groups of workers based on their life stage and increased emphasis on using the Internet to view or request SOCs. | |

Targeting specific population groups. SOC inserts were created for each target age group. Different information was sent to individuals new to the labor market and just beginning to contribute to the CPP, to persons nearing retirement, and to older individuals who had not yet applied for benefits. Although inserts are no longer included with the printed SOC that is mailed out, this information is still available in the online SOC.

Previously, rather than receiving a standard SOC, new contributors to the CPP received a welcome letter that introduced the CPP and contained valuable information about the plan. A slightly truncated version of the SOC was sent to individuals in the 18–29 age range. The truncated version did not include estimates for retirement, disability, and survivor benefits.

SOCs mailed to individuals aged 59–64 included a letter with information relevant to preretirees and an insert promoting online application for a CPP retirement pension. Older participants who had not yet applied for benefits were sent an SOC, a letter inviting them to apply for benefits, a simplified application, and an information sheet detailing the support documents required.

Online Access. The SOC has been available online since 2005. The creation of the online SOC was part of two government initiatives—Modernizing Services for Canadians and Information on the Retirement Income System—to provide services and information electronically. All workers who have contributed to the CPP are able to access information on their earnings, contributions, and estimated benefits and view a copy of their SOC by creating a My Service Canada account.

The use of the online SOC is encouraged through targeted mailing of promotional inserts in existing mass mailings, promotional messages within standard correspondence with workers, and through the Service Canada website home page.

Surveys. The Canadian government commissioned five surveys from 1999 through 2006 that either focused directly on the SOC or included questions about the statement. The purpose of most of the surveys was to assess the public's awareness of the SOC, evaluate its impact on attitudes, and determine the usefulness of information provided. Four of the surveys focused on specific age cohorts and one survey covered workers who were eligible for a retirement benefit but had not yet applied. The 1999 survey applied only to younger workers who received the truncated version of the SOC. The 2002/2003 survey asked respondents for their views on the SOC's content, frequency of delivery, and mode of delivery. However, the 2005 survey was conducted primarily to understand workers' use of the Internet and of the government's online services. The 2006 survey asked workers about their experience with the CPP and included several questions about the SOC. Table 2 compares some of the responses to certain questions.

| Variable | 1999 a | 2001 | 2002/2003 | 2005 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number surveyed | 801 | 1,200 | 1,218 | 1,211 | 820 |

| Ages and age group(s) surveyed | 18–29 | 30–49; 50–70 |

18–24; 25–34; 55–64 |

18–30; 55–59; 63 |

59–60; 70–80 |

| Received the SOC | 52% (ages 18–24); 79% (ages 25–29) | 83% | 83% | 33% (ages 18–30); 85% (ages 55–59 and 63) | 85% (ages 59–60); 54% (ages 70–80) |

| Read the SOC b | 68% | 78% | 75% | 70% (ages 18–30); 81% (ages 55–59 and 63) | 75% (ages 59–60); 39% (ages 70–80) |

| Found the SOC easy to understand b | 75% | 90% | 87% | -- | -- |

| Found the SOC useful | 32% (ages 18–24); 44% (ages 25–29) | 73% | 71% (ages 25–34 and 55–64) | -- | -- |

| SOURCE: Gregg Zentner (personal communication with the authors via e-mails and internal memoranda from Service Canada, 2011–2013). | |||||

| NOTE: -- denotes data not available. | |||||

| a. The 1999 survey applied only to younger workers who received the truncated version of the Statement of Contributions (SOC). | |||||

| b. Among respondents who received the SOC. | |||||

In addition to the summary results shown in Table 2, further survey findings include the following responses, some of which were limited to one survey:

- In 1999, approximately 75 percent of respondents who read the SOC stated that they kept both the SOC and the insert and that they checked their personal benefit and contribution information.

- In 2001, 81 percent of respondents said the information was important to them personally.

- In 2002/2003, 70 percent of respondents stated that having read the SOC and CPP informational insert, they had a better understanding of the CPP and the services it provides and were more likely to plan for their retirement. Sixty-three percent of respondents who read the SOC stated that they would like to receive an SOC every year, and 73 percent said they preferred to receive this information by regular mail.

- In 2005, 81 percent of the older respondents and 70 percent of the youngest respondents who recalled receiving a SOC said that they read it and filed it with their personal records.

- In 2006, 67 percent of respondents aged 70–80 knew they were eligible to receive a CPP pension.

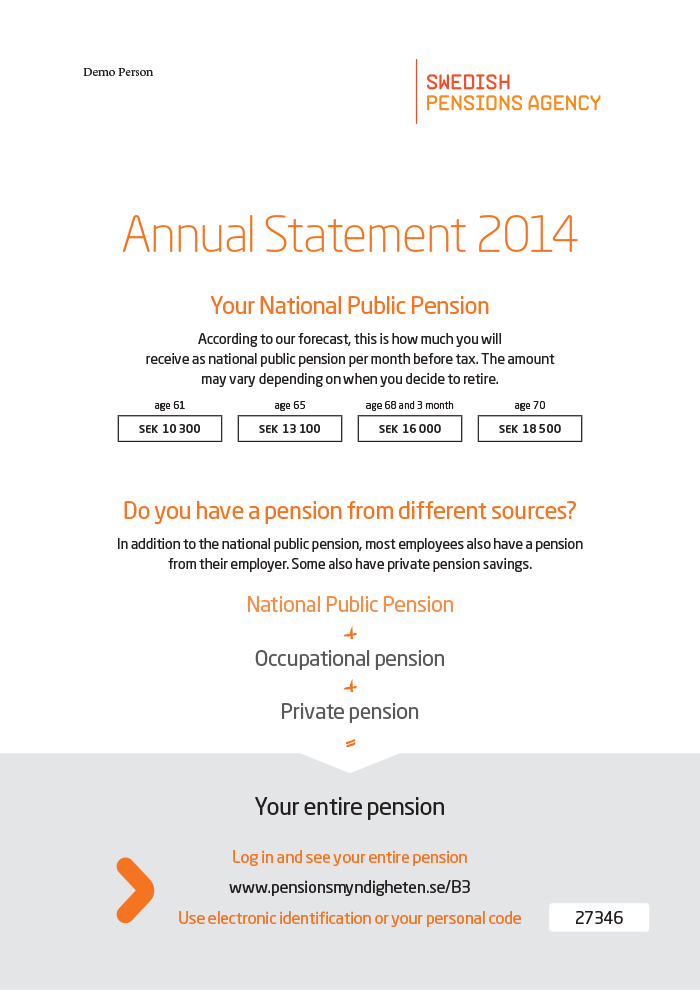

Sweden: Orange Envelope

Sweden's public pension statement, the Orange Envelope,11 was introduced in 1999 to coincide with the introduction of the new multipillar pension system.12 At the same time, the government launched a separate public information campaign to educate workers about the new system. The statement is called the Orange Envelope because once a year the Swedish Pension Agency (SPA) sends it by mail in a bright orange envelope; the color orange was chosen to distinguish it from other types of government mail. According to the law, anyone with pension rights (that is, anyone who has contributed to the system) during the previous year must receive a statement (Nyqvist 2008).

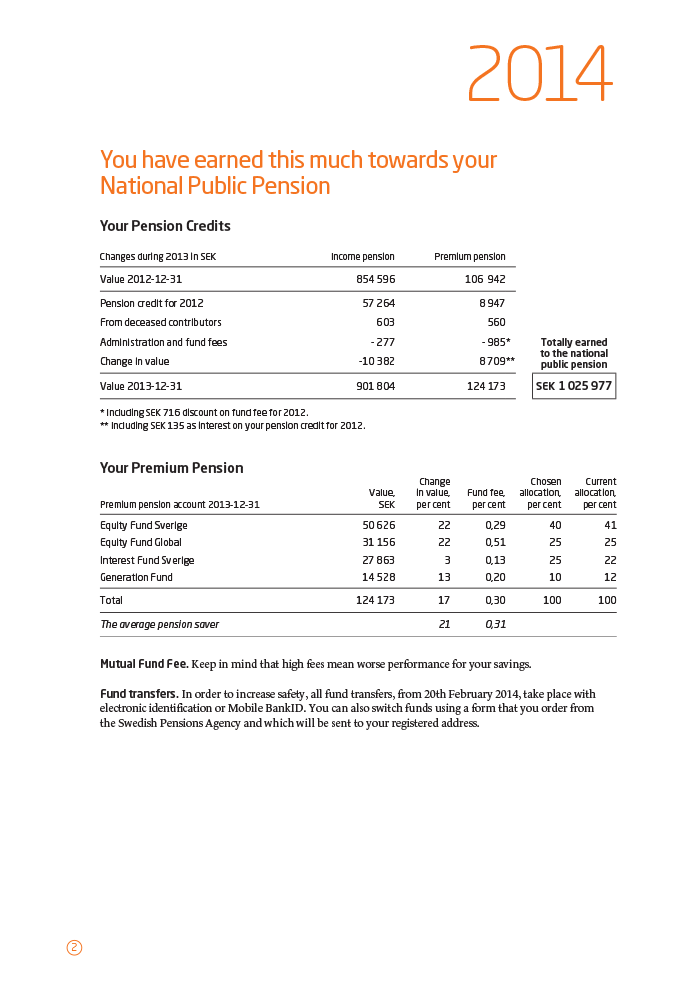

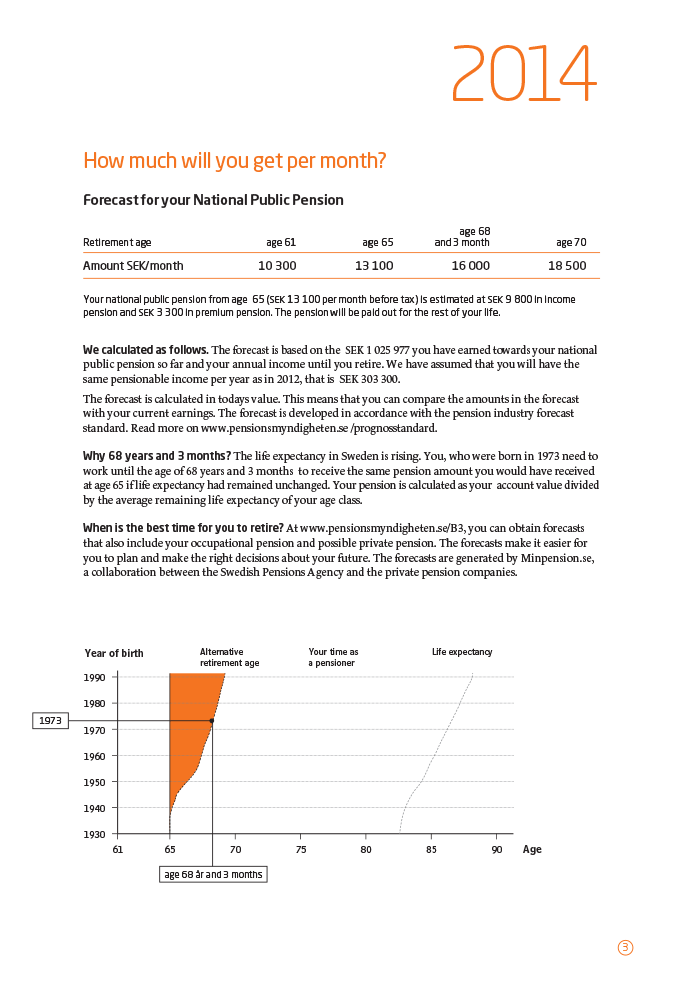

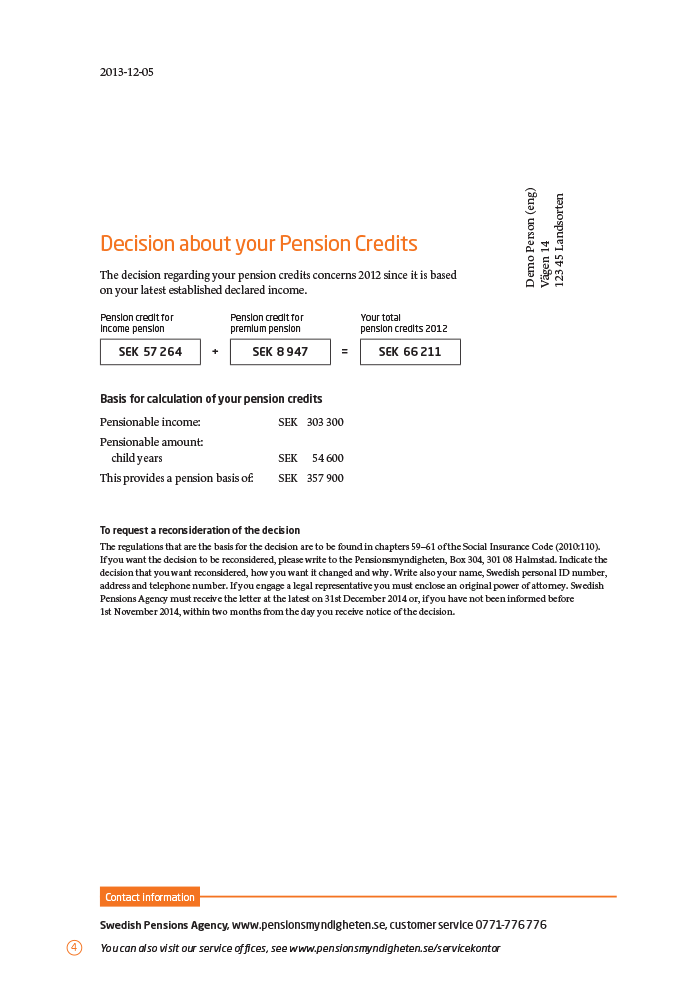

Contents. The Orange Envelope provides personal information on the NDC and premium pension accounts (called the national public pension): (1) the value of each account (including the changes in value since the last statement), (2) pension credits for each account (based on information from 2 years before), (3) administrative and fund fees charged for each account, and (4) the amount received for the survivor bonus for each account (the pension balance of workers who have died before reaching the age of retirement, which is distributed among the surviving members of their birth cohorts). For the premium pension account, there is also a breakdown by fund, the allocation of each fund that the accountholder chooses, and the actual distribution.

Until 2011, the statement presented estimates under two scenarios: (1) 0 percent wage growth (personal and national average income) for the NDC account plus a 3.5 percent annual rate of return for the premium pension; and (2) 2 percent wage growth for the NDC account plus a 5.5 percent annual rate of return for the premium pension. The higher assumption was removed beginning in 2011 because surveys indicated that it was too confusing. Table 3 presents a chronology of major changes to the Orange Envelope.

| Year of statement | Major content changes | Number of pages |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 a | Pension rights based on 1995, 1996, and 1997 earnings records | 4 |

| 2000 | Expanded information on pension rights back to 1960 | 8 |

| 2001 | Added information on the credit for pursuing higher education or military service | 4 |

| 2002 | Added premium pension information | 6 |

| 2005 | Eliminated much of the general information | 6 |

| 2006 | Introduced a separate statement for citizens turning age 22 in 2006, with an explanation of how the system works | 6 |

| 2007 | Introduced three different statements targeting specific population groups; began promoting the Minpension website | 6 |

| 2009 | Added two graphics: a pyramid to describe the three pillars and “piggy banks” to emphasize the importance of saving | 6 |

| 2011 | Eliminated the forecast of benefits using 2 percent growth in wages so that there would be only one assumption, 0 percent growth in wages; included an insert to explain the decrease in benefits for that year | 6 |

| 2012 | Added a transitional retirement age to forecast benefits and a graph and text to explain the relationship between increasing life expectancy and retirement age; increased the font size and added more white space; included a separate insert announcing that forecasts are available online for the total pension (national, occupational, and private) | 6 |

| 2013 | Redesigned the first page to announce that the Orange Envelope is available online and individuals may opt out of receiving a paper copy | 6 |

| 2014 | Eliminated the “piggy bank” graphics (because of the limited space in the shorter length) and redesigned the entire statement; provided access codes to online information and stressed the importance of all three pillars of the retirement income system. | 4 |

| SOURCES: SPA (2002–2014); Nyqvist (2008); Arne Paulsson (personal communication with the authors via e-mails, 2011–2015). | ||

| a. First Orange Envelope. | ||

Targeting specific population groups. Since 2007, there have been three different basic versions of the Orange Envelope (with some variation, by population subgroup). The first version is geared to general pension savers (insured persons who have been contributing to social security); the second version is for new pension savers (new entrants to the labor force); and the third version is for old-age pensioners (fully or partially retired). The new pension savers receive almost the same version as the one for general pension savers; new savers receive a separate insert with general information on choosing funds, while the general savers receive specific information about their premium pension choices.

There are also three different variations of the Orange Envelope sent to pensioners. The most common variation contains a statement of expected pension payments for the next year, the status of the individual's premium pension account, and a statement with the previous year's pension payments and tax deductions (which is also sent to the Tax Authority). The second variation applies to pensioners who are still working and paying contributions who also receive information on their pension credits for the previous year. The third variation applies to pensioners who have drawn only their premium pension who also receive a statement of their pension payments for the next year.13

The statement provides projected benefit amounts for workers at different ages, depending on the age of the insured worker. For example, the statement for workers aged 60 or older provides projected benefit amounts for additional ages from 61 to 70 (the specific ages used vary according to the age of the insured worker). All statements provide a transitional age to emphasize the effect of increasing life expectancy on retirement age (the age at which the insured worker must retire in order to receive the same benefit amount that he or she would have received at age 65 if there had been no increase in life expectancy since 1995). (Parliament passed the pension reform law in 1995, and the pension reform was implemented in 1999.)

Online access. Workers can access pension information on all three components (national, occupational, and private pensions) of Sweden's retirement income system, including a combined projected pension through PensionsMyndighen, which links to the Minpension website.14 According to the Minpension website, to date, about 96 percent of the occupational pension providers and about 90 percent of the private pension providers are linked to its website. At the beginning of 2014, common standards for forecasting pensions were introduced for all three components. Each individual must have his or her own password to access the site. Individuals can also opt out of receiving the paper copy of the statement. Because of the 2014 advertising campaign that focused on accessing the information online, 120,000 new users registered, bringing the total number to 2.1 million; as of July 2015, there were 2.3 million users. Mobile phone users may download an “App” to their iPhone or Android, which enables online access.

The SPA also supplements the pension information in the Orange Envelope. The PensionsMyndigheten website makes available a detailed explanation of the most recent statement plus some other basic information regarding the country's retirement income system. The Minpension website provides a toolkit with links to additional information. Local SPA offices offer meetings with individuals at age 60 who live in the area. The purpose of those meetings is to provide more detailed information about pensions, discuss the effects of retirement at different ages, and describe the application process. The SPA advertises these meetings locally and on its website.

Surveys. About 1 week after individuals should have received the Orange Envelope in the mail, the SPA follows up with a survey that has been conducted every year since 1999.15 The survey involves about 2,000 phone interviews from a random sample of members of specific population groups: general pension savers, new pension savers, and old-age pensioners.

Table 4 provides selected survey results for the Orange Envelope, from 2007 through 2014, for each of the three specific population groups. The share of respondents who acknowledged receiving the envelope and opening it has increased over time. During the same period, the portion of respondents that found the statement difficult to understand decreased, and the portion that found it easy to understand increased. In 2014, from 64 percent (general savers) to 69 percent (new savers and pensioners) of respondents found the Orange Envelope easy to read.

| Selected survey question | General pension savers | New pension savers | Old-age pensioners | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2011 | 2014 | 2007 | 2011 | 2014 | 2008 | 2011 | 2014 | |

| Received the envelope | 89 | 94 | 95 | 74 | 88 | 82 | 89 | 95 | 94 |

| Opened the envelope | 78 | 83 | 82 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 96 | 95 |

| Read all of the contents a | 14 | 15 | 21 | . . . | 14 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 33 |

| Read part of the contents a | . . . | 71 | 68 | . . . | 59 | 69 | . . . | 62 | 61 |

| Did not ready any of the contents a | . . . | 13 | 10 | . . . | 26 | 16 | . . . | 10 | 6 |

| Found the contents easy to understand a,b | 57 | 58 | 64 | 43 | 62 | 69 | 57 | 58 | 69 |

| Found the contents difficult to understand a,c | 20 | 12 | 9 | 28 | 17 | 9 | 20 | 12 | 8 |

| SOURCE: SIFO (2011–2014). | |||||||||

| NOTE: . . . = not applicable. | |||||||||

| a. Among respondents who opened the envelope. | |||||||||

| b. "Easy" includes "easy" and "very easy." | |||||||||

| c. "Difficult" includes "rather difficult" and "very difficult." | |||||||||

More recent results from the 2014 survey include the following:

- Most respondents (81 percent) thought the information provided was sufficient.

- Most (89 percent) would consider using the Internet to obtain more information about their pensions.

- A small portion (12 percent) would use the online version instead of a hard copy of the statement, compared with about half (51 percent) who would not do so.

Based on the results of each annual survey, the contents and/or format of the statement has changed over time. For example, the word count in the 2005 statement was half that of the 2002 statement. Table 3 shows content and format changes to the Orange Envelope, from the first statement in 1999 through 2014.

National advertising campaign. Every year, to raise public awareness about the Orange Envelope and its contents, the SPA conducts a national advertising campaign using a variety of media (television, newspapers, billboards, and so forth) that follow the annual mailing of the statement from February through March. The message has been different each year (refer to the accompanying box for selected themes from past annual media campaigns in Sweden). Banks and insurance companies often conduct their own media campaigns that coincide with the government campaign. Those companies often use the same “orange trademark” as that used by the government to advertise pension insurance and pension savings accounts (Nyqvist 2008). At the same time, reports on the public pension system, including the projected level of benefits, often appear in the various news media (Larsson, Paulsson, and Sundén 2011).

- There is a new pension system and this is where you find information about it. (1999)

- Your pension consists of three parts: the national public pension, the occupational pension, and possible private savings. (2000)

- The entire lifetime is counted. (2002)

- This year your Orange Envelope contains something extraordinarily valuable. (2003)

- Have you accumulated more or less than the average Svensson? (2004)

- Pictures of sliced carrots describe the different components of the national pension system. (2005)

- Piggy banks (emphasizing the importance of savings) correspond to the change in the design and format of the statement. (2009)

- Forecasts are available for everybody. (2014)

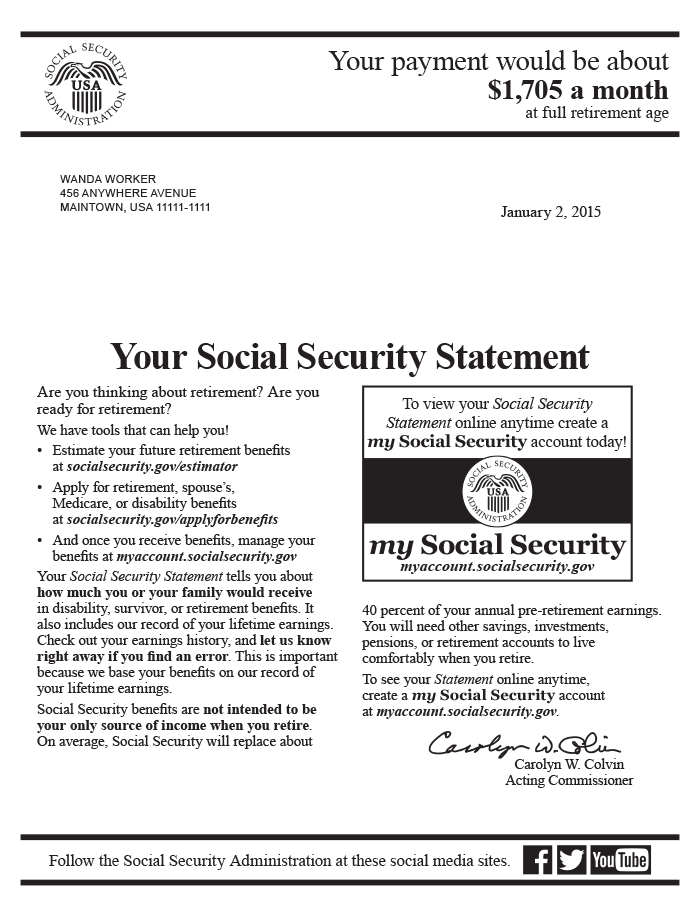

United States: Social Security Statement

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is required by law to send out the Social Security Statement,16 the public pension statement of the United States. The Omnibus Budget and Reconciliation Act of 1989 (OBRA 89) amended the Social Security Act to require SSA to issue estimated benefit and earnings statements beginning in 1995. OBRA 89 mandated that SSA send statements to workers aged 60 or older in fiscal years (FYs) 1995–1999 and to workers aged 25 or older in FY 2000 and subsequent FYs. SSA modified this schedule so that statements were sent to increasingly younger groups of workers in FYs 1996–1999.

All workers in the United States who have a Social Security number, have wages or net earnings from self-employment, and are not currently receiving Social Security benefits are eligible to receive a Social Security Statement. Currently, SSA is sending the Statement to workers aged 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 or older who have not created a my Social Security account to access the Statement online.

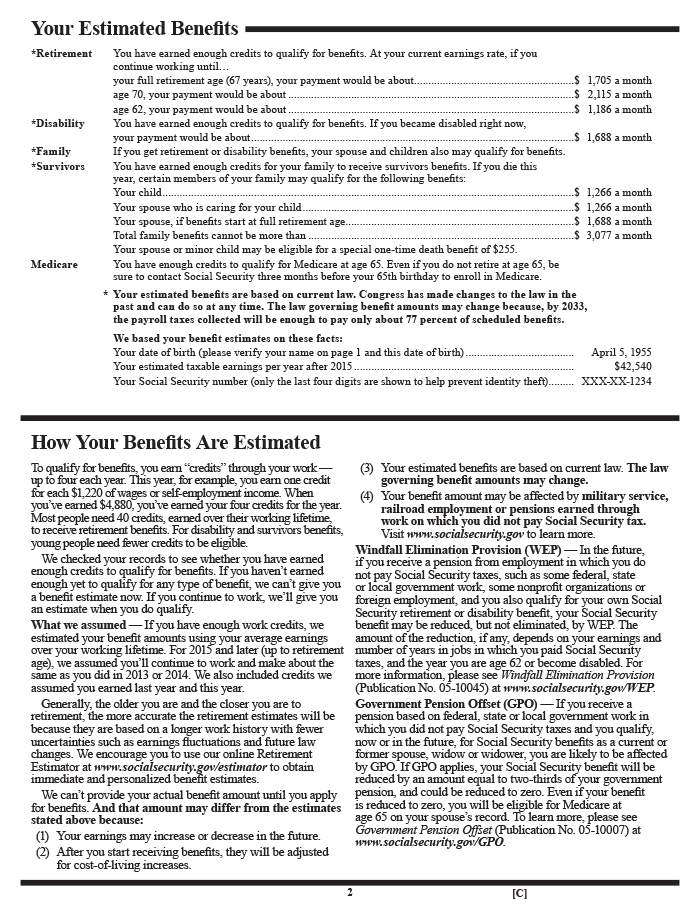

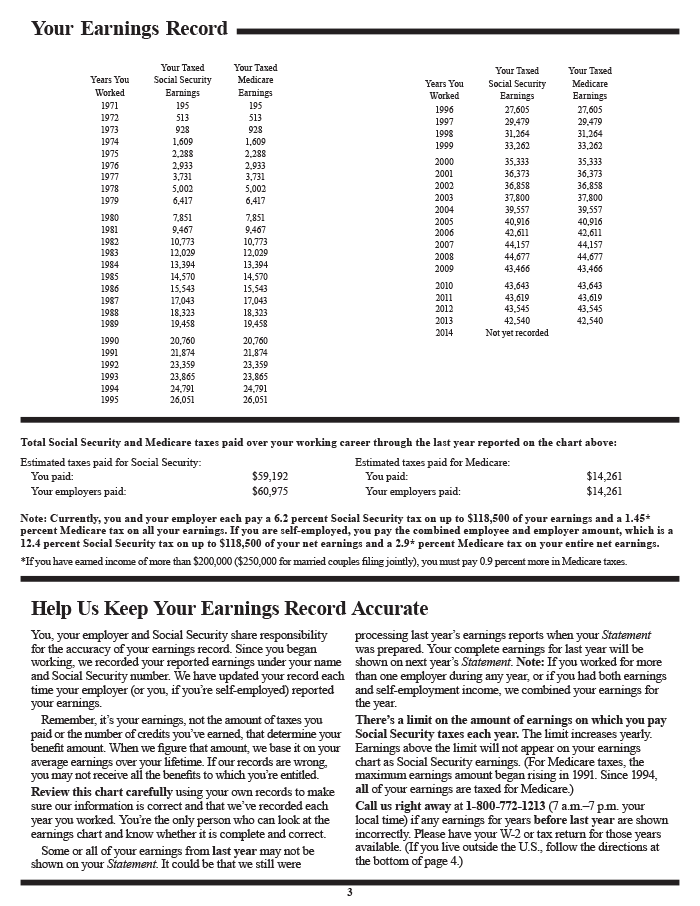

Contents. Legislation determines the basic content of the Statement. OBRA 89 specified that Statements contain the worker's earnings history; the Social Security and Medicare taxes paid by the worker; an estimate of potential retirement benefits at the early retirement age of 62, at the FRA, and at age 70; estimates of disability, survivor, and other auxiliary benefits potentially payable on the worker's account; and a description of benefits payable under Medicare. In addition, the first page of the Statement contains a message from the Social Security commissioner.

In FY 2000, when SSA began sending Statements to all eligible workers aged 25 or older, a paragraph was added that encouraged the recipient to think about the advantages and disadvantages of retiring early. A list of publications on topics related to retirement benefits also appeared.

The Social Security Protection Act of 2004 mandated the addition of sections on the windfall elimination provision (WEP) and the government pension offset (GPO) to the Statement beginning in 2007. WEP and GPO determine how pensions earned through work not covered by Social Security affect receipt of Social Security benefits. Other changes to the Statement included adding the agency's website address to the first page and expanding the discussion of how benefit amounts are calculated.

Frequency. From FY 2000 to March 2011, SSA mailed Statements annually to all eligible workers aged 25 or older. In FY 2010, SSA sent out 151 million Statements, which equates to over 12.5 million mailed every month, or about 415,000 each day. Workers received their Statement approximately 3 months before their birthday.

In March 2011, after several years of increasing budget constraints, SSA suspended Statement mailings in order to conserve funds. In February 2012, the agency resumed targeted mailings, sending printed Statements to eligible workers aged 60 or older. In July, SSA resumed first-time mailings to eligible workers at age 25. However, in October, in response to an increasingly difficult budget situation, the agency suspended all Statement mailings, including on-request mailings.

In September 2014, SSA resumed mailing printed Statements to workers at ages 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and those aged 60 or older who had not created a my Social Security account to access the Statement online. The partial restoration of mailed Statements was made possible by an improved budget.

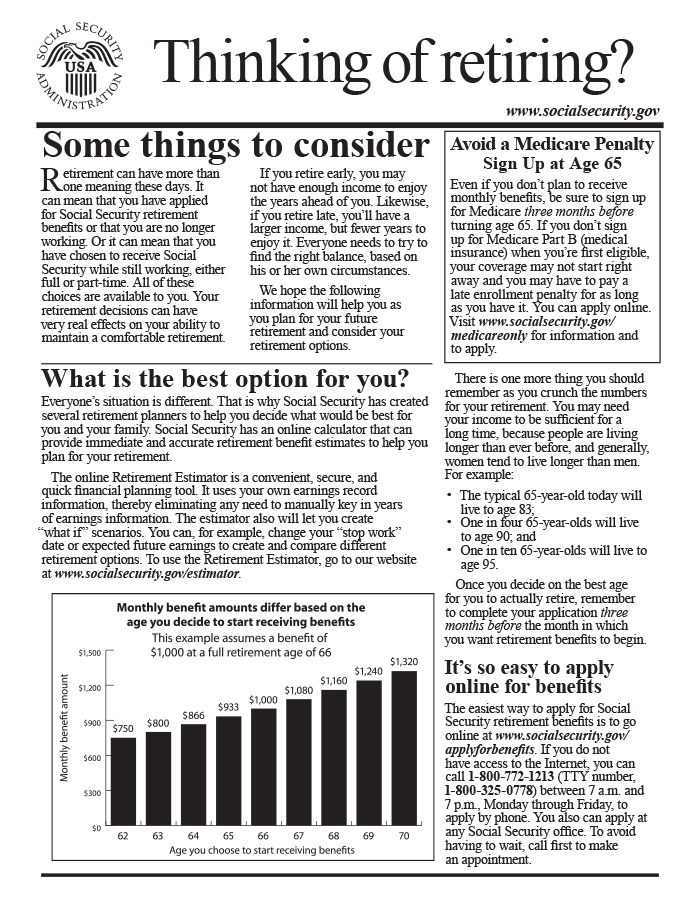

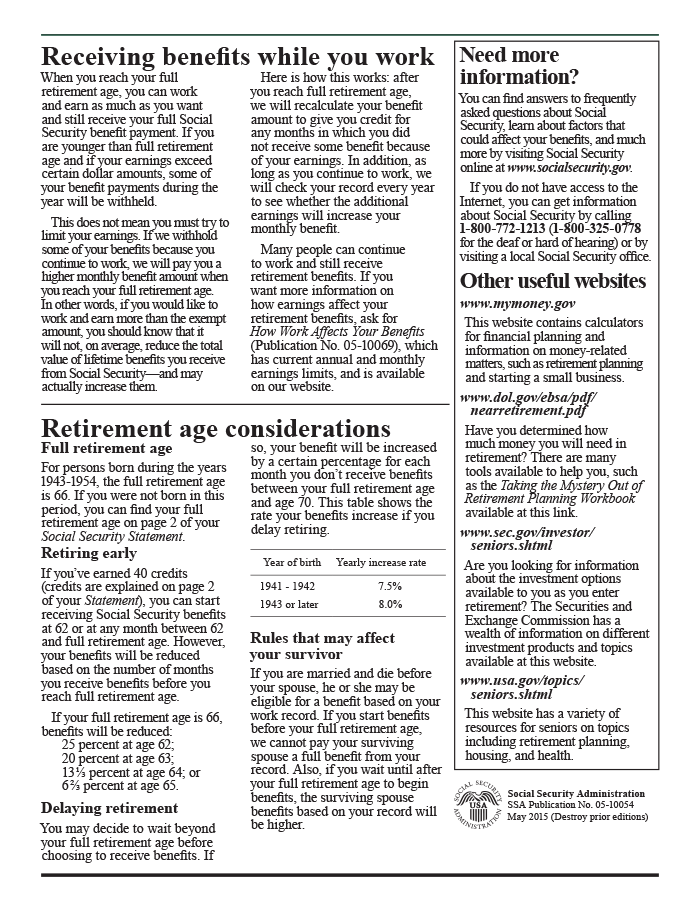

Targeting specific population groups. SSA began sending out special age-targeted inserts with the Social Security Statements. Beginning in October 2000, the first such insert, Thinking of retiring?, was sent to individuals aged 55 or older. It contains information about the effects of claiming Social Security benefits at age 62, at the FRA, or at age 70, and the effects of working after claiming benefits—as well as the implications of each option for the beneficiary and his or her survivors. The insert also contains information on applying for Medicare, and it lists websites and phone numbers providing more information about Social Security benefits, retirement planning, investment options, and housing and health issues.

In February 2009, SSA began sending an insert to workers aged 25–35, What young workers should know about Social Security and saving. This insert describes the future finances of Social Security, the nonretirement benefits provided by Social Security (such as disability and survivor benefits), and the importance of saving to supplement Social Security benefits. It also lists websites providing information about saving and investing.

Online access. In May 2012, SSA launched an online version of the Social Security Statement to provide workers with immediate access to their earnings records, estimated benefit amounts, and related information. Although the print version is mailed only to eligible workers aged 25 or older, the online Statement is available to all individuals aged 18 or older. An individual must set up a my Social Security account in order to have access to the online Statement.

The online Statement includes links to other information, such as an insert for workers aged 55 or older, and to other online services and tools. In the first week after its launch, more than 130,000 individuals visited the SSA website and viewed their online Statements. In the first 6 months of FY 2015, online Statements were viewed 20.2 million times.

Surveys. As the agency was implementing the Social Security Statement, it sought to measure the Statement's effect on public awareness of and knowledge about Social Security. SSA identified this objective in its strategic plans and commissioned surveys to assess the Statement's impact.

Strengthening public understanding of Social Security programs was one of the five goals of SSA's Strategic Plan 1997–2002: Keeping the Promise, issued in September 1997. In 1998, as part of that strategic plan, SSA established the Public Understanding and Management System, under which it commissioned the Gallup Organization to conduct six surveys from 1998 through 2004 to evaluate the agency's outreach efforts, including the Statement.

The first survey, conducted in 1998, was a baseline study to determine what the public knew about Social Security. It found Americans relatively well informed about basic program facts. Respondents recognized the three primary benefits (retirement, disability, and survivor); they understood the tax used to support Social Security; they knew how those taxes were being used and how benefits were calculated; and they understood the challenges to long-term program finance posed by an aging population. However, Americans were less informed about specific program facts. Only 38 percent knew that the FRA in 1998 was 65, and only 46 percent knew that the early retirement age was 62. Those who stated they had received the Social Security Statement were better informed than those who did not recall receiving the Statement.

The 2001 Gallup survey found a significant increase in the number of respondents who knew about the relationship between Social Security benefits and earnings, how benefits were financed, that benefits increased automatically as the cost of living rises, and that the FRA was increasing. Slightly more than half of the respondents reported receiving the Statement. Respondents who reported receiving the Statement were more knowledgeable about the program than those who did not.

In 2008, SSA commissioned Abt SRBI to survey the public about the Social Security Statement and how well it provided information about SSA programs, aided financial planning, and verified earnings. A baseline survey was conducted in 2008 with follow-up surveys in 2009 and 2010. The 2010 survey found that 62 percent of respondents recalled seeing their benefit information, and 45 percent recalled seeing their earnings history. Twenty-two percent of respondents aged 55 or older reported reading the special insert, Thinking of retiring? Thirty percent of all respondents and 42 percent of respondents aged 55 or older reported using the Statement for financial planning. Seventy percent of respondents thought the information in the Statement was useful for retirement planning. Fifty-four percent expressed overall satisfaction with the Statement's information about savings and investment. The surveys found that the Statement was most effective in the verification of earnings, with about 95 percent of respondents reporting that their personal information was correct. Table 5 provides a chronology of the developments of the Social Security Statement.

| Time period | Development |

|---|---|

| 1939 | The 1939 Amendments to the Social Security Act required the Social Security Board (SSB) to maintain records of wages paid to individuals, and, on request, to provide individuals with information on their wages. |

| 1940 | The SSB established regulations governing the revision of wages by individuals. |

| 1962 | The Social Security Administration (SSA) initiated the “leads” program, under which it sends information on benefit entitlements to older insured workers who have not yet claimed benefits. |

| 1970s to early 1980s | SSA engaged in internal discussions on providing workers of all ages with benefits and earnings statements, and began doing so automatically as well as on request. |

| Early 1980s | SSA began sending benefit estimates to workers on request, under a little-publicized program. |

| 1981 | The National Commission on Social Security, appointed by President Carter, recommended that SSA provide information on Social Security benefits to workers, at a minimum; to those who request it; and ideally, to all workers automatically. |

| August 1988 | Senator Moynihan introduced a bill mandating that SSA issue earnings and benefits statements. The same day, SSA Commissioner Hardy announced that the agency would begin providing the Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate Statement (PEBES) on request. |

| 1989 | The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 (OBRA 89) amended the Social Security Act to require SSA to issue “Social Security account statements” and to begin sending them automatically according to a set schedule. OBRA 89 also specified the information to be included in those statements. SSA modified these specifications, going beyond legislative requirements. |

| 1994 | SSA began test mailings of the PEBES to plan for future workloads. Questionnaires and focus groups gathered input and feedback on the wording and design of the PEBES. |

| Fiscal year (FY) 1995 | SSA began phasing in automatic mailing of earnings and benefit statements to continue through FY 1999. |

| 1996 | SSA pretested its online PEBES. |

| 1997 | SSA began national testing of the online PEBES. Concerns raised by the media and Congress about the privacy of earnings records caused SSA to suspend the online PEBES. |

| 1999 | The PEBES was redesigned and renamed the Social Security Statement. |

| FY 2000 | SSA began mailing Social Security Statements to workers aged 25 or older. The agency sent out 134.7 million Statements. |

| October 2000 | SSA began mailing a special insert—Thinking of retiring?—to workers aged 55 or older. |

| 2007 | SSA added sections to the Social Security Statement on the windfall elimination provision (WEP) and the government pension offset (GPO), as mandated by the Social Security Protection Act of 2004.a |

| February 2009 | SSA began mailing special inserts—What young workers should know about Social Security and saving— to workers aged 25–35. |

| March 2011 | SSA Commissioner Astrue testified before Congress, stating that to conserve funds, the agency would have to temporarily suspend mailing the Social Security Statement. Work began on developing an online Statement. |

| 2012 | In February, SSA resumed annual mailings of printed Social Security Statements to all workers aged 60 or older; in May, the agency launched an online version of the Statement accessible to workers of all ages; in July, it conducted a one-time mailing of Statements to workers aged 25; and in October, SSA suspended Statement mailings. |

| September 2014 | SSA resumed annual mailings of printed Social Security Statements to workers aged 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 or older who had not yet established a my Social Security account to access their Statement online. |

| SOURCE: Adapted from Smith and Couch (2014). | |

| a. The WEP and the GPO determine how pensions earned through work not covered by Social Security affect receipt of Social Security benefits. | |

National advertising campaign. SSA promotes the online Statement as part of the my Social Security national marketing campaign and the Campaign for a Secure Retirement. The agency uses a variety of methods including public service announcements, billboards, seminars, webinars, exhibits at conferences, outreach to advocacy groups, and advertisements posted on Facebook.

Comparison of the Public Pension Statements in Canada, Sweden, and the United States

In this section, we provide an overview of some similarities and differences between the public pension statements in all three countries (Table 6). Each of the countries is required by law to provide a statement. Sweden is the only country that must provide the statement to all active workers every year; in Canada, the requirement is to mail a statement upon request; in the United States, the requirements (which groups receive the mailings and the mailing frequency) have changed over the years. The Swedish and U.S. statements include special inserts or mailings to target groups and provide projected benefit amounts at different ages. Canada does not include any special inserts when it mails the SOCs (Service Canada staff, personal communication with the authors, September 11, 2015).17 Canada and the United States also provide projections for disability and survivor benefits.18 All three countries provide online projections, but only Sweden offers a projection that includes each of the three pillars of the retirement income system.

| Comparison category | Canada | Sweden | United States |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retirement ages | 65 (full) 60 (early) Up to 70 (deferred) |

Flexible beginning at age 61; no upper limit | 66 a (full) 62 (early) Up to 70 (deferred) |

| Legal basis | 2011 law | Part of the 1999 pension reform law | 1989 law |

| Year of first mailing | 1984 | 1999 | 1995 b |

| Frequency | Last mass mailing occurred in 2013; Statement of Contributions (SOCs) can still be requested | Yearly (from February through March) | Yearly for persons aged 60 or older; every 5 years for those younger than age 60 |

| Current recipients | Persons aged 18 or older who earn a wage or salary and have contributed to the CPP can request SOCs | Anyone aged 28 or older who has contributed during the previous year; with no contributions, at ages 22, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 64 | Persons aged 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 or older who have not yet set up an online account |

| Special insert or mailing | Inserts not included with requested SOCs | New entrants to the labor force, workers already in the labor force, and old-age pensioners | Persons aged 25–35 and those aged 55 or older |

| Ages for pension projections | 60, 65, and 70 | 61 and 70 c | 62, 66 or 67,a and 70 |

| Online access | Since 2005 | Since 2004 | Since 2012 |

| Forecasts for other types of public pensions | Disability and survivors | None | Disability and survivors |

| Surveys | 1999–2006 | Annual | 1998–2004; 2008–2010 |

| SOURCES: Authors' compilation using pension statement data from this article. | |||

| a. The full retirement age is currently 66 and is gradually rising to age 67 by 2027. | |||

| b. The Social Security Statement was first mailed out in 1999 (fiscal year 2000). Its predecessor, the Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate (or PEBES), was first mailed out in 1995. | |||

| c. An additional age is provided that represents the increase in life expectancy—how long an individual must work to receive the same pension amount that he or she would receive at age 65 if life expectancy had remained unchanged. The pension is based on life expectancy of the individual's cohort. These rules apply to individuals born in 1954 or later. Special transition rules apply to those born between 1938 and 1953. | |||

All three countries conduct or have conducted surveys regarding the statement. Sweden's survey is administered annually, after the Orange Envelope has been mailed. Over time, the number of survey questions has increased and new topics have been added, such as online access. The results of the Swedish surveys indicate increasing awareness of and knowledge about the information in the statement. Both the United States and Canada have conducted a series of surveys, but not on an annual basis. In the United States, the results include a rise in the number of respondents who were aware of program facts. In Canada, a relatively high percentage of respondents acknowledged receiving and reading the SOC.

Changes to the statement format and content in both Sweden and the United States have originated from different sources. In Sweden, the statement has been modified regularly based on the results of their annual survey. In fact, over time, the Orange Envelope has evolved from 10 dense pages to 4 pages with a lot of “white space.” Not only the length but also the content has changed. The changes to the U.S. Social Security Statement have been mainly related to content. The first Statement reflected significant design changes (focus-group tested) from its predecessor, the Personal Earnings and Benefit Estimate Statement, including fewer pages. In addition, laws mandated that certain information be included in the Social Security Statement. Finally, the content of the Social Security commissioner's message changed when new commissioners took office. By contrast, Canada does not conduct regular reviews of the contents and format of the SOC. It only makes changes when new relevant legislation has been enacted or if a high-level appeal proves that the information provided in the SOC has been misleading (Service Canada staff, personal communication with the authors, September 11, 2015).

In Sweden, a national advertising campaign is conducted each year to correspond with the mailing of the Orange Envelope. The United States includes the Social Security Statement as part of the my Social Security national marketing campaign. Canada, on the other hand, does not conduct any national advertising campaigns. It does, however, provide information about the online SOC in Service Canada's walk-in centers and on public websites (Service Canada staff, personal communication with the authors, September 11, 2015).

Conclusion

As we have noted in this article, increases in life expectancy and changes to public and private pensions have emphasized the importance of governments providing workers with pertinent information about the public pension system and the benefits those workers can expect to receive. Adequately informing workers about their public pension benefits involves three aspects: (1) providing the appropriate content in a clear and understandable way, (2) ensuring that the content is easily accessible and readily available to the public, and (3) regularly evaluating both the content and the way in which that material is offered to the public so that the information and the way it is disseminated remain relevant in changing economic and demographic contexts. The countries reviewed here have taken different approaches to these three aspects of providing information to the public. The differences can offer insights to improving the statements in each of the three countries.

Our review of the public pension statements in Canada, Sweden, and the United States found that all three countries provide estimates of expected retirement benefit amounts. Canada and the United States also provide a record of earnings so that recipients of the public pension statement can verify that their earnings record is accurate. Surveys in the three countries indicated that the public found the statements useful and easy to understand. The U.S. Social Security Statement provides links to interactive retirement planning tools and cites additional retirement-related SSA publications. The Canadian SOC provides a hyperlink to Service Canada, but gives no additional information on where to find explanations of various aspects of the program. The Swedish Orange Envelope includes a web address and instructions on how to set up an online account to access specific information, as well as how to obtain information in person. For individuals who do not have a computer or are not computer literate, the methods of access discussed here may be problematic.

We also found that in general, all three countries have similar demographics, but have different experiences in making changes to their public pension systems to address the financial pressures caused by aging populations. The Social Security Amendments of 1983 gradually raised the retirement age in the United States from age 65 to 67. In the late 1990s, Canada changed the benefit formula, the contribution rates, and how the reserve fund was invested, while Sweden switched from a pay-as-you-go public pension system to a two-pillar (NDC and premium pension) system. In addition, both Canada and Sweden set up automatic-adjustment mechanisms to keep their systems in balance.

In all three countries, the governments could consider making changes to their statements to better inform workers of the general financial state of the public pension programs. In the United States, the results of a recent Gallup (2015) poll showed that 51 percent of workers surveyed did not believe that Social Security benefits would exist when they reach retirement age. At one time, the Social Security Statement included a note stating that should the trust fund reserve balances reach zero, there would still be enough revenue from contributions to fund some 77 percent of a worker's benefit; SSA might consider including such information once again. Both Canada and Sweden might also consider adding some general statements regarding the positive financial state of their respective systems. In Canada, the CPP Investment Board (2015) announced that the most recent actuarial report indicated that the CPP is projected to be sustainable over the next 75 years. In Sweden, a special insert was included in the Orange Envelope when the automatic-adjustment mechanism was applied and benefits were temporarily reduced. Sweden might consider adding a note to the Orange Envelope stating the yearly status of the system.

In addition, information on benefits paid to family members is important. Both the Canadian and the U.S. statements include projected survivor benefit amounts. However, in Sweden, the NDC plan does not provide survivor benefits and the premium pension only provides survivor benefits if the insured worker purchased voluntary survivor insurance. The Orange Envelope does include pension credit “from deceased contributors,” with no explanation. (It is the “survivor bonus” described earlier.) The United States also has spousal and children's benefits linked to the insured worker's earnings record. It would be helpful if an explanation was included in the Social Security Statement on how the age at which a worker claims his or her own retirement benefits affects that worker's family benefit levels.

An important aspect of disseminating information to the public is ensuring that the public receives the information—that the information is provided in a way that is accessible and accords with how the public would like to receive it. Sweden mails out a public pension statement every year, and recent surveys found that almost all of the respondents acknowledged receiving the statement. A 2002/2003 Canadian survey found that 63 percent of respondents who read the SOC wanted to receive it every year, and 73 percent wanted to receive it by mail. A 2010 SSA-commissioned survey conducted by Abt SRBI found that 79 percent of respondents preferred to receive the Social Security Statement by mail, with 14 percent preferring online access.

Despite the public preference for mailed statements, Canada recently suspended the regular mailing of its SOCs, and the United States has limited the number of Social Security Statements it mails. In FY 2010, the United States mailed annual Statements to all eligible workers aged 25 or older. Now it mails Statements annually to workers aged 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, and 60 or older who have not yet set up an online account. All three countries offer the public access to online statements. However, in the United States, there were only slightly more than 34 million visits to the online Statement in FY 2015. That corresponds to about 17 million unique users, compared with the 150 million workers who received a mailed Statement in FY 2010. As of 2011, the online SOC in Canada had received 1 million hits, likely corresponding to fewer unique users, compared with 13 million SOCs that were mailed out in the 2001–2002 period (Gregg Zentner, personal communication with the authors via e-mails and internal memoranda from Service Canada, 2011–2013).

It is expensive to disseminate public pension statements by mail. Thus, it is understandable that Canada decided to stop regular mailings of the SOCs (available only on request) and that the United States has limited the number of Social Security Statements it mails. However, because recipients prefer receiving mailed statements, Canada might consider whether mailing SOCs every 5 years to its select population groups—new entrants, those approaching retirement, and those eligible but not yet claiming pensions—is a viable option. Both Canada and the United States might also consider commissioning surveys and research to determine how best to encourage the public to use the online statements and to identify low-cost alternative ways of providing information about pensions to the public.

All three countries conduct or have conducted evaluations of their public pension statements, with each country taking a different approach. Sweden conducts annual evaluations, with the questions focused primarily on whether the Orange Envelope recipients read and understood the information. Canada commissioned several surveys from 1999 through 2006 that targeted different age groups; the surveys focused on whether the SOC recipients read and understood the information. By contrast, the Social Security Statement evaluations in the United States attempt to assess how much the public understands about Social Security benefits and programs. Surveys conducted from 1998 through 2004 are tied to SSA's strategic-plan objective of improving public knowledge about Social Security. Those surveys asked specific questions about Social Security benefits and programs, enabling the agency to determine that public knowledge about various aspects of Social Security was indeed increasing. Given the switch in Canada and the United States to greater reliance on online provision of public pension statements, it would be interesting for those countries to evaluate how much the public currently knows about benefits and programs and the degree to which the change from mailed statements to online provision has had on the public's understanding of public pension benefits.

Appendix A: Canada—Statement of Contributions

Appendix B: Sweden—Orange Envelope

Appendix C: United States—Social Security Statement

Appendix D

| Comparison category | Austria | Belgium | Germany | United Kingdom |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retirement age | 65 (men) and 60 (women); gradually rising to 65 (women) from 2024 to 2033 | 65 (men and women) | 65 and 4 months; gradually rising to 67 (men and women) by 2029 | 65 (men) and 62 (women); gradually rising to 65 (women) by 2018; to age 66 from 2019 to 2020 and to age 67 from 2026 to 2028 (men and women) |

| Legal basis | Beginning in 2014, statements were sent to all insured workers; previously, statements were provided upon request | Mandatory for private-sector employees at age 55; voluntary for public-sector employees | Mandatory | None; administrative function of the government |

| Frequency | No information | Summary reviews provided annually; entire work history provided every 5 years | Provided every 3 years | Provided upon request |

| Current recipients | All insured persons born after 1954 with at least 1 month of contributions | Private-sector employees; expected to send to public-sector employees in the near future | Insured employees and self-employed persons aged 55 or older | Persons residing in the country who are at least 4 months younger than the State Pension Age (retirement age) |

| Basis of calculating an old-age pension | Contributions paid for workers who retire at the normal retirement age | Actual gross salaries for actual working period and notional salaries for equivalent periods for workers who retire at the normal retirement age (adjusted calculations for early and deferred retirement are provided upon request) | Average earnings in the past 5 years; 1 percent and 2 percent annual increase in income | Current value for workers who retire at the normal retirement age (adjusted calculations for early and deferred retirement are provided upon request) |

| Online access | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Forecasts for other types of public pensions | None | None | Disability and spouse's pensions | None |

| Integrated information | None | None | None | Yes |

| Additional information | Internet, call center, contact provider | Internet, contact in person and by phone | Internet, informational pamphlets, contact in person and by phone a | Internet b |

| SOURCE: European Union (2013). | ||||

| NOTE: Based on answers to country surveys. | ||||

| a. In addition to the public pension statement, insured workers aged 27 or older who have at least 5 years of contributions receive a pension communication document that contains information on how pensions are calculated; a projected old-age pension based on the insured worker's average earnings in the past 5 calendar years; contribution history (both employer and employee); the current full disability pension amount; and the effect of future adjustments on that pension. | ||||

| b. The government provides facilities for personal communication. | ||||

Notes

1 In this section, the source of information is either U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA 2014) or (SSA, forthcoming) unless otherwise noted.

2 OAS is a nearly universal pension financed by general revenue. Its clawback feature (also called a recovery tax) reduces or eliminates the OAS benefit for higher earners. In 2013, about 6 percent of all OAS beneficiaries were affected by either a reduced or no benefit, depending on the income level.

3 Guaranteed Income Supplement, an income-tested benefit, is provided to low-income OAS pensioners.

4 The different components of retirement income systems are often described as pillars. For example, first-pillar pensions in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are often pay-as-you-go public pension systems, and second-pillar pensions could consist of mandatory occupational pensions or of mandatory or voluntary individual accounts.

5 The guarantee pension, funded from general revenue, is a guaranteed income-tested benefit (income tested only against the national earnings-related pension—the NDC and premium pension) paid at age 65 to residents with no or a low earnings-related pension.

6 An old-age Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payment is made to individuals at age 65 with low income and limited resources. The means test (associated with SSI eligibility) is based on earned and unearned income, including benefits. Benefits are adjusted automatically according to changes in the cost of living.

7 Quarters of coverage are based on the insured worker's annual earnings. In 2016, the minimum amount of earnings to receive 1 quarter of coverage is $1,260. This amount is adjusted annually to reflect past increases in average wages.

8 Unless otherwise noted, the source of information on the Canadian SOC is Gregg Zentner (personal communication with the authors via e-mails and internal memoranda from Service Canada, 2011–2013).

9 Included in CPP's proactive mailings in the 1980s was a Terms and Conditions (TC) document that described CPP coverage and contributions as well as eligibility and payments for all benefits including those for old-age, disability, and survivors. The TC also provided information on appeals; international agreements; and special situations, such as the division of pension credits and the childcare drop-out provision. Although the intention in the beginning was to send a TC document along with the very first SOC a worker received, more recent mailings have not included that document.

10 As of 2011, the online SOC website had received 1 million hits, likely corresponding to fewer unique users, compared with 13 million SOCs that were mailed out in the 2001–2002 period (Gregg Zentner, personal communication with the authors via e-mails and internal memoranda from Service Canada, 2011–2013).

11 Unless otherwise noted, the source of information on the Orange Envelope is Arne Paulsson (personal communication with the authors via e-mails, 2011–2015).

12 For details of the Swedish national public pension program, refer to the section that provides a description of the public pension systems in the three countries.

13 The 2010, 2011, and 2014 Orange Envelopes that were sent to pensioners also contained an information sheet explaining that pensions were reduced because of the automatic-balancing mechanism. An automatic-balancing mechanism is applied if the system is in imbalance (assets and liabilities are not equal). Both the notional interest rate and the indexation of current benefits are reduced (temporarily) in order to bring the system back into balance.

14 PensionsMyndigheten (http://www.pensionsmyndigheten.se) is an SPA website devoted to retirement, which provides an individual access to a password-protected personal retirement page . In addition to accessing the information from the Orange Envelope, an individual may apply for an old-age pension on this website. Minpension (http://www.minpension.se) is an independent company comprising a public/private partnership—50 percent government and 50 percent private providers (Paulsson 2008).

15 The SPA contracts out the survey. Before the SPA was created (in 2010), the Swedish Social Insurance Agency was in charge.

16 Unless otherwise noted, the source of information on the Social Security Statement is Smith and Couch (2014).

17 Until 2012, Canada sent out mass mailings with targeted inserts. The information formerly contained in those inserts continues to be available online.

18 Sweden's disability program is administered by a different agency than the one that administers the old-age and survivor program. There are no survivor benefits per se under the NDC program, and survivor benefits under the premium pension are available if the insured worker purchased voluntary survivor insurance.

References

CPP Investment Board. 2015. Long-Term Sustainability of Canada Pension Plan. Sustainability Backgrounder: Chief Actuary's Report. Toronto, ON Canada: Public Affairs and Communications (May). http://www.cppib.com/content/dam/cppib/Our%20Performance/Sustainability%20of%20the%20Fund/CPPIB%20Sustainability%20Backgrounder%20Q4%20F2015.pdf.

European Union. 2013. The Right to Retirement Pension Information. Peer Review in Social Protection and Social Inclusion: Synthesis Report. Madrid, Spain: European Commission (July).

Gallup. 2015. “In Depth—Topics A to Z: Social Security.” http://www.gallup.com/poll/1693/social-security.aspx.

Larsson, Paul, Arne Paulsson, and Annika Sundén. 2011. “Customer-Oriented Services and Information: Experiences from Sweden.” In Priority Challenges in Pension Administration, edited by Noriyuki Takayama, chapter 9. Tokyo, Japan: Maruzen Co. Ltd.

Nyqvist, Anette. 2008. “Opening the Orange Envelope: Reform and Responsibility in the Remaking of the Swedish National Pension System.” Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropology (64). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University, Department of Social Anthropology.

Paulsson, Arne. 2008. Pension Information in Sweden. Social Insurance Agency (Swedish: Försäkringskassan).

SIFO. 2011–2014. “Uppföljning av det Orange Kuvertet (follow-up of the Orange Envelope).” Unpublished survey reports.

Smith, Barbara A., and Kenneth A. Couch. 2014. “The Social Security Statement: Background, Implementation, and Recent Developments.” Social Security Bulletin 74(2): 1–25.

SPA. See Swedish Pension Agency.

SSA. See U.S. Social Security Administration.

Sundén, Annika. 2009. “The Swedish Pension System and the Economic Crisis.” Issue Brief No. 9–25. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College Policy (December).

Swedish Pension Agency. 2002–2014. “Annual Statement.”

U.S. Social Security Administration. 2014. Social Security Programs Throughout the World: Europe, 2014. Washington, DC: Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics (September).

———. Forthcoming. Social Security Programs Throughout the World: The Americas, 2015. Washington, DC: Office of Retirement and Disability Policy, Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics.