Testimony by Stephen C. Goss,

Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration,

before the Senate Committee on Budget

July 12, 2023

Chairman Whitehouse, Ranking Member Grassley, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to speak to you about the Social Security program, past, present, and future.

Social Security started paying monthly benefits to qualifying retired workers and their family members and survivors in 1940. Benefits for disabled workers and their families started in 1957. Over the 84 years through 2023, all scheduled benefits have been paid in full.

The Challenge of 1983: The Last Major Changes Made to the Program

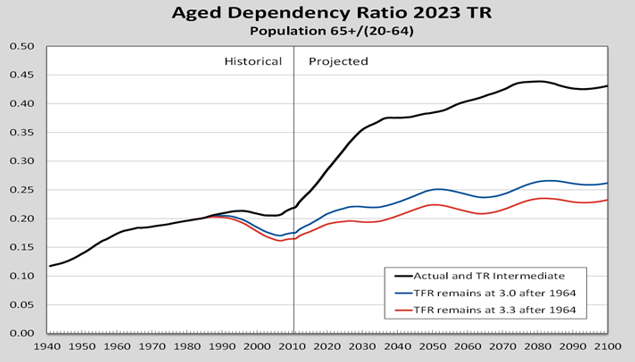

In 1982, the Old-Age and Survivors (OASI) Trust Fund faced immediate crisis. The fund’s reserves were depleted, requiring temporary borrowing from the Disability Insurance (DI) and Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Funds. The 1983 Amendments quickly followed, making changes needed to address immediate shortfalls and to begin addressing the impending shift in the age distribution of the US population. This shift was already foreseen, based on the drop in the birth rate after 1965. We well understood at the time that the 1983 Amendments were not a permanent solution to Social Security’s long-term shortfalls.

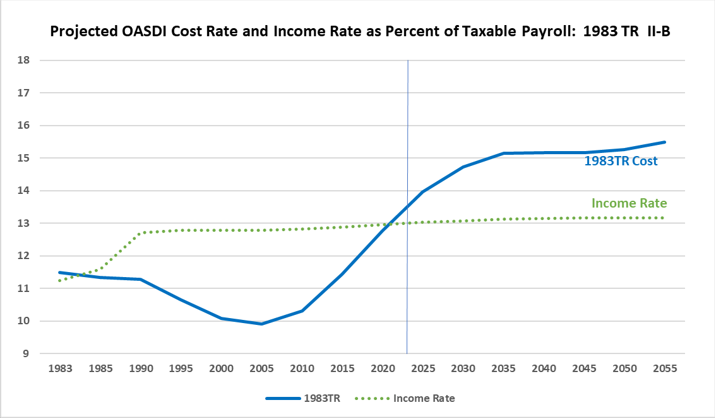

In 1983, we knew that in 2008 the baby-boom generation (those born in 1946 through 1965) would begin retiring and would gradually be replaced at working ages by the subsequent lower-birth rate generations. Excess annual income through 2020 was projected to accumulate to cover shortfalls through the mid-2050s. It was known that further action would be needed by that time.

The Challenge of 2023: The Additional Changes That Are Needed

So why are we now facing a need for action to avert trust fund reserve depletion in the mid-2030s, 20 years sooner than expected in 1983? The age distribution of the population has followed expectations with continued low birth rates and modest increases in life expectancy at age 65. (Note that the increase in life expectancy at age 65 projected in the 1982 Trustees Report through 2015 matched the actual outcome.)

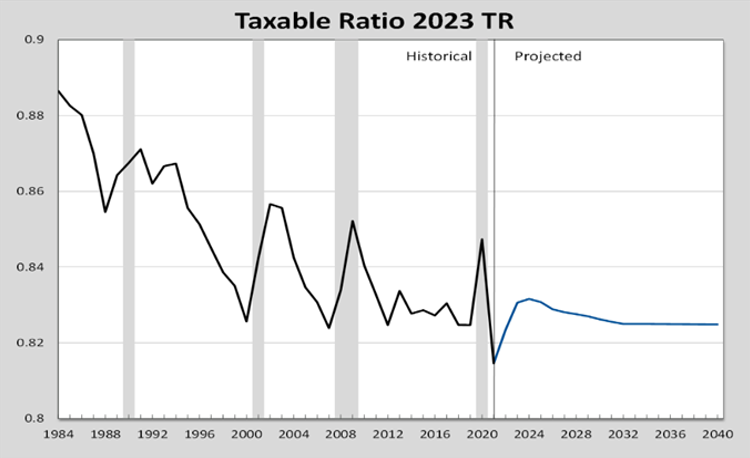

The primary unexpected change was the large relative increase in earnings for the highest earners. In 1982, the OASDI maximum taxable earnings level was set such that about 90 percent of covered earnings were subject to the payroll tax, and the level was scheduled to increase with the average wage in the economy. Assuming similar annual increases in average earnings at all levels, this approach was expected to maintain 90 percent of earnings below the taxable maximum and thus subject to payroll tax. Between 1983 and 2000, however, earnings for those with earnings above the taxable maximum (the highest 6 percent of earners) rose much faster than the overall average, lowering the percent of covered earnings below the taxable maximum to only 82.5 percent. Other than temporary effects from recessions, this “taxable ratio” has remained at about the same level since 2000, and we expect it to remain there in the future.

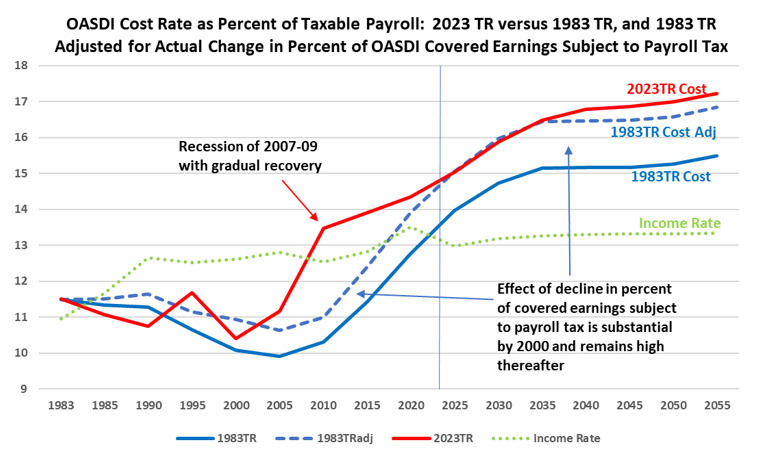

The other major unexpected change since 1983 was the performance of the economy, in particular the deep recession of 2007-09. Recovery from that recession was gradual and incomplete in terms of expected labor productivity, or real output per hour worked.

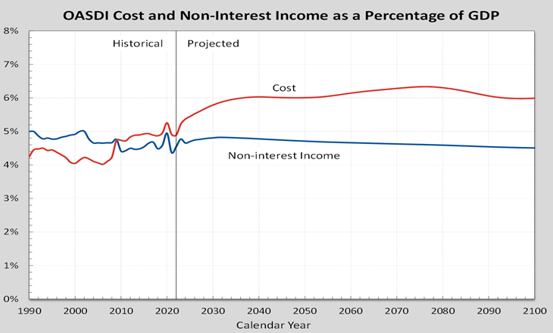

The chart below illustrates the impact of these two major unexpected events that have occurred since 1983. First, the dashed blue line shows the effect of the diminished share of covered earnings subject to payroll tax, on the cost of the OASDI program as a percent of taxable payroll. Program cost as a percent of the diminished taxable payroll by 2000 and thereafter is elevated from the projected levels in the 1983 Trustees Report as shown on the solid blue line to nearly the level projected in the 2023 Trustees Report as shown on the red line. Second, the recession of 2007-09 and the very gradual recovery that followed increased OASDI cost above income earlier than had been expected, reducing anticipated trust fund accumulations.

Thus, while the 1983 Amendments made an excellent start at addressing the long-term challenge of the changing age distribution of the US population, more change was then known to be needed, and the time for further change is sooner than had been expected due to unanticipated changes in the economy. We need to close the gap between the program’s cost rate and income rate before reserves become depleted in 2034, finishing the work started in 1983, and addressing the unanticipated drop in the share of covered earnings subject to the payroll tax. To close this gap, we will need to raise program income by about one-third, lower scheduled benefits by about one-fourth, or some combination of these approaches.

A more permanent solution to the Social Security financing shortfall requires attaining “sustainable solvency,” a concept developed in the mid-1990s in conjunction with Bob Ball and others on the 1994-96 Social Security Advisory Council, and with Senators Bob Kerrey and Alan Simpson. Sustainable solvency requires that trust fund reserves as a percent of annual program cost be stable or rising at the end of the 75-year long-range projection period. This condition was not met or intended in the 1983 Amendments.

Actuarial Status in the 2023 OASDI Trustees Report

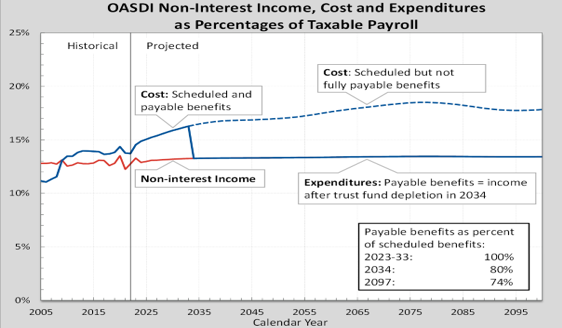

The cost of providing scheduled benefits under current law has been rising as a percent of taxable payroll (all covered earnings below the annual taxable maximum amount) since 2008, and it will continue to rise by 2040 to a relatively stable level above scheduled program income. This rise is attributable to the long-recognized changing age distribution in the population.

The financial shortfall over the next 75 years as a whole for the OASDI program, or unfunded obligation, amounts to $22.4 trillion in present value, which represents 3.42 percent of taxable payroll and 1.2 percent of GDP over the entire period. This shortfall over the entire 75-year period must be met with changes over the entire 75-year period in order for full scheduled benefits to be paid on a timely basis.

Similar to the trends as a percent of taxable payroll are the trends as a percent of GDP.

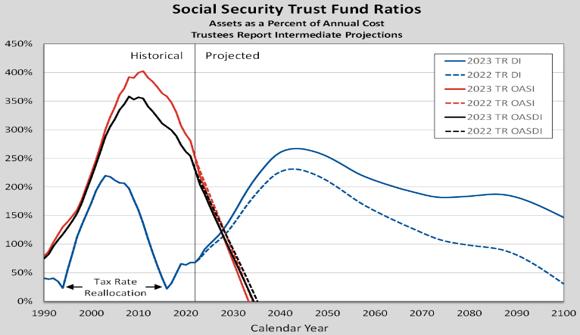

The current reserves in the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds total $2.8 trillion, more than double the amount of annual program cost. However, under the intermediate assumptions of the 2023 Trustees Report, revenues to the combined funds are projected to be less than program cost in future years, so that combined OASI and DI reserves would become depleted in 2034 in the absence of legislation. At that time, 80 percent of scheduled benefits would still be payable. The OASI Trust Fund alone is projected to deplete its reserves in 2033, with 77 percent of scheduled benefits then payable. These dates are both 1 year earlier than projected in the 2022 Trustees Report. The DI Trust Fund alone is projected to be fully financed beyond 2100.

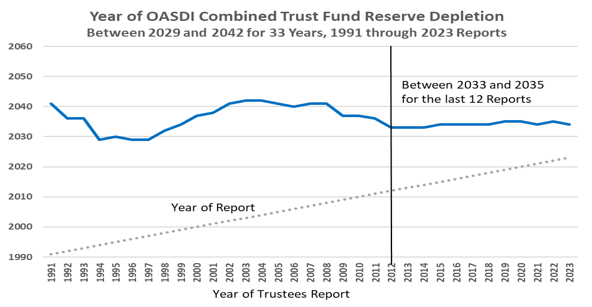

The assessment of the actuarial status of the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds provided in the annual Trustees Reports since 1941 tells us by when, and to what degree, changes in scheduled revenue and/or scheduled benefits will be needed. The Trustees’ assessment has been remarkably consistent and stable in recent decades. The year of projected combined OASI and DI Trust Fund reserve depletion has been in the range of 2029 to 2041 in the last 33 annual reports, and in the range of 2033 to 2035 in the last 12 reports.

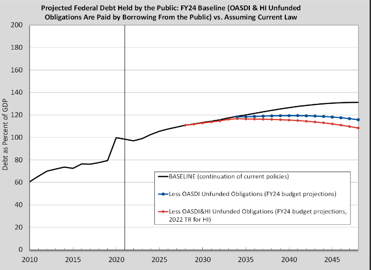

Social Security and Federal Debt

The fundamental nature of these trust funds is important. These funds are credited with all income to the OASDI program on a daily basis and provide the sole source for paying benefits and administrative expenses. If at any point reserves were to become depleted with program cost still exceeding continuing income, then scheduled benefits would not be fully payable on time. The OASDI program and the Trust Funds do not have any authority to borrow from the General Fund of the Treasury or the public and never have. It should be noted that the President’s Budget and CBO project federal debt by making an assumption that current law will be changed in the future, requiring the General Fund to borrow sufficient amounts from the public to cover any shortfall for OASI, DI, and the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund after reserve depletion. This assumption is based on a specific requirement in Sec. 257(b)(1) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985, P.L. 99-177 (codified at 2 U.S.C. §907(b)(1) (2016)):

“Laws providing or creating direct spending and receipts are assumed to operate in the manner specified in those laws for each such year and funding for entitlement authority is assumed to be adequate to make all payments required by those laws.”

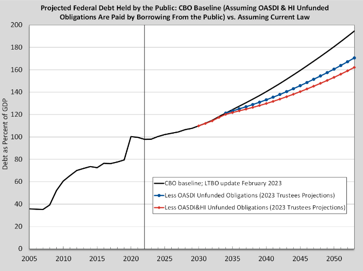

The graphs below show recent projections of publicly held debt as a percent of GDP with this assumed change in law (black line) and the debt levels that would actually occur under current law and policy (blue and red lines).

Under current law, Trust Fund reserves are invested only in Treasury Bonds, thus reducing the amount that must be borrowed from the public due to past deficits for all other federal programs. When trust fund reserves are drawn down in order to maintain full Social Security benefits, such redemption has no effect on the total federal debt subject to limit or on on-budget federal deficits. Such draws on reserves just require shifting some federal debt from debt owed to the trust funds to debt owed to the public. This shift in federal borrowing has been projected years in advance, so it is no surprise to the financial markets. Moreover, it is understood that any unfunded obligation that exists when reserves might become depleted would almost certainly be met with Congressional action, in the form of legislation providing either additional tax revenue or a reduction in scheduled benefits, as has always been done in the past.

Critical Factors for Projections: Historical Experience and Assumptions for the Future

Age Distribution

The rise in the cost of the Social Security program between 2008 and 2040, as a percent of both taxable payroll and GDP, follows directly from the changing age distribution of the adult US population, as seen in the familiar aged dependency ratio graph shown below.

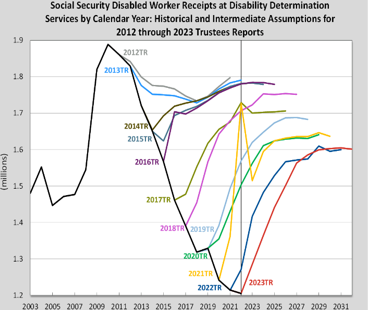

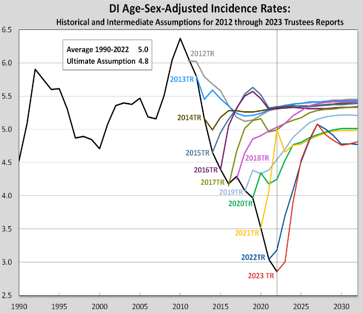

Disability

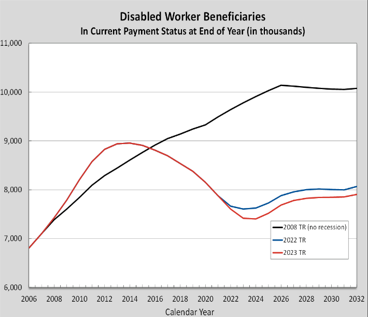

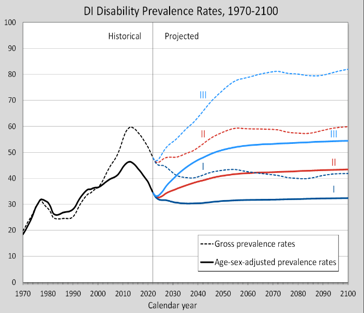

Applications for disability benefits and incidence rates have been declining steadily since 2010 and have continued to be below our prior projections. We and the Trustees continue to assess the reasons for these declines and the likelihood that rates will rise to levels not seen since the period immediately after the 2007-09 recession.

The total number of beneficiaries paid from the DI Trust Fund has now been falling since 2013. As a result, the disability prevalence rate (recipients in current payment status as a percent of the insured population), has also dropped to levels not seen for 20 years. Only with the assumed return of disability incidence rates back to much higher levels will the prevalence rate rise to the level seen before the 2007-09 recession.

Many factors have played a role in the lower disability incidence rates and prevalence rates. Among these are the changing nature of work and the increasing accommodation of workers with some limitations, given the changing age distribution of the adult population.

Employment

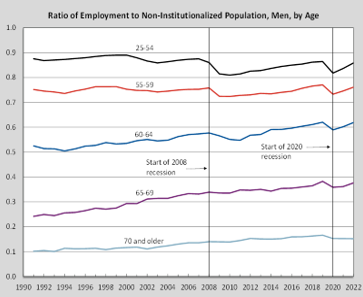

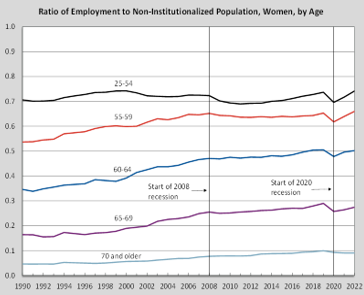

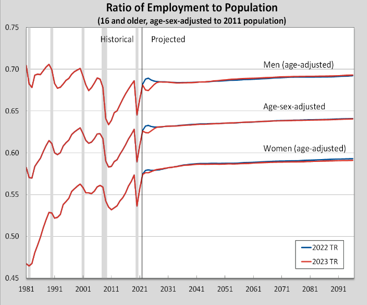

Additional evidence of the effect of the changing age distribution is the increased employment of those over age 60 since 1990.

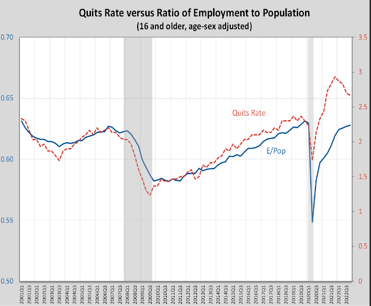

The pandemic has had significant effects on employment, but the drop in employment during the 2020 recession was brief with an extraordinarily fast recovery. The “quits rate” indicates the rate of workers voluntarily leaving a job, often due to the opportunity for a higher paying job in a high labor demand environment. After a brief drop in the employment rate in the assumed economic slowdown in 2023, we project the future employment rate to remain at about recent peak levels.

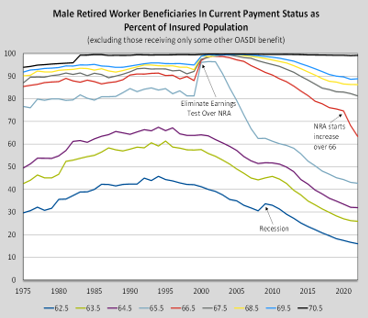

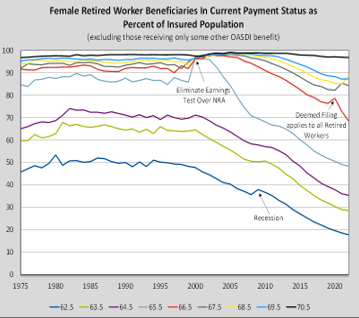

With the changing age distribution and demand for workers, age at retirement and age at start of receipt of Social Security retirement benefits continues to rise.

Mortality

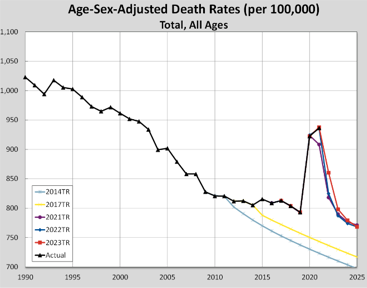

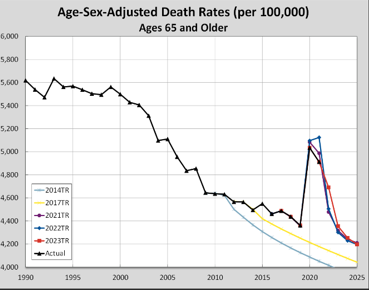

Mortality is also an important factor in the cost of the Social Security program. Declines in death rates slowed considerably after 2009, not only in the US but also in the United Kingdom and Canada.

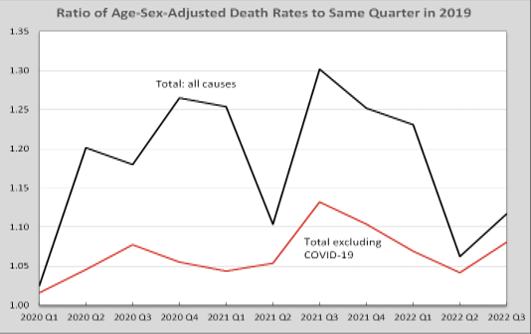

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically elevated death rates. Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have been assuming that in the long term, two factors would roughly balance out: (1) individuals with preexisting health conditions are more likely to die from acute COVID, meaning that the surviving population might be healthier, and (2) the surviving population who lived through the pandemic have potentially suffered negative effects from having been infected, including post-COVID conditions. As a result, we project that age-sex adjusted death rates will return to the path seen between 2009 and 2019.

However, there are concerns about the magnitude of effects on the residual population. Provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics show that during 2020, 2021, and 2022, death rates for causes other than COVID have been elevated above the level seen in 2019.

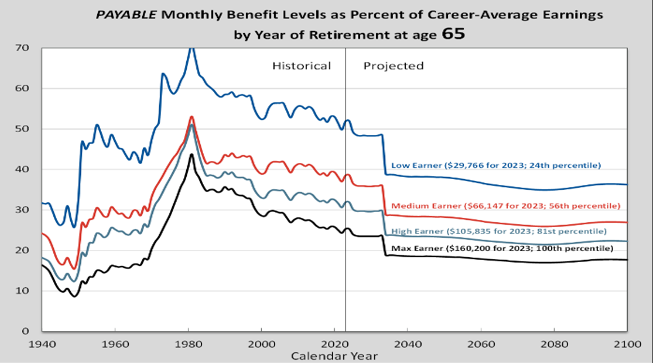

Benefit Levels

Benefit levels scheduled in current law vary by workers’ career average earnings levels. Monthly benefits are designed to replace a larger percentage of career average earnings for lower earners. The “replacement rates” shown below for benefits as a percent of career average earnings at selected levels indicate the impact that trust fund reserve depletion could have in the absence of a future change in law, assuming that benefits would be reduced for all by the same percent if reserves were allowed to become depleted. Benefit levels are shown for retirees at the earliest eligibility age (62) and the average age of starting retired worker benefits (65). All benefits in 2034 would be reduced by 20 percent if there is no change in law, even if the allocation of payroll tax rates between OASI and DI were adjusted as was done to maintain DI benefits in 1995 and 2015.

Conclusion

We face a challenge to build on the 1983 Social Security Amendments and to correct their shortcomings, in order to ensure that the OASDI program will continue to be strong and adequately financed into the future.

- First, the 1983 Amendments were an interim solution to the well-understood changing of the age distribution due to the drop in birth rate after 1965. These Amendments were expected to extend the ability to pay scheduled benefits from 1982 to the mid-2050s, with the clear understanding that further changes would be needed by then.

- Second, the redistribution of earned income to the highest earners was not anticipated in 1983. This shift resulted in about 8 percent less payroll tax revenue by 2000 than had been expected, with this reduced level continuing thereafter. The severity of the 2007-09 recession was also not anticipated.

- Third, with the passage of 40 years since 1983, we clearly see the shortcomings of the 1983 Amendments in achieving “sustainable solvency” for Social Security. We are now in a position to formulate further changes needed, building on the start made in 1983.

- Fourth, the long-known and understood shift in the age distribution of the US population will continue to increase the aged dependency ratio until about 2040, and in turn increase the cost of the OASDI program as a percentage of taxable payroll and GDP. Once this shift, which reflects the drop in the birth rate after 1965, is complete, the cost of the program will be relatively stable at around 6 percent of GDP. The unfunded obligation for the OASDI program over the next 75 years represents 1.2 percent of GDP over the period as a whole.

We look forward to working with this Committee and others in developing the adjustments to the law that will be needed to keep the Social Security program in good financial order, providing retirement, disability, and survivor benefits for future generations.

Again, thank you for the opportunity to talk about the actuarial status of the Social Security program. I will be happy to answer any questions you may have.