Deputy Commissioner, Social Security Administration

before the

House Committee on Ways and Means,

Subcommittee on Social Security

January 24, 2012

Chairman Johnson, Ranking Member Becerra, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for inviting me to discuss our efforts to preserve the integrity of our disability programs. I am the Social Security Administration’s Deputy Commissioner, as well as the Accountable Official for improper payments. We make every effort to pay benefits to the right person in the right amount at the right time. Accordingly, one of our strategic goals is to preserve the public’s trust in our programs.

Due to tight budgets in fiscal years (FY) 2011 and 2012, we have suspended or postponed lower priority activities so that we can continue to achieve our most important goals— eliminating the hearings backlog and focusing on program integrity work. Our available funding in FY 2012 is almost $400 million less than what we operated with in FY 2010. At the same time, our fixed costs and our workloads continued to increase. We lost over 4,000 employees in FY 2011, and we expect to lose over 3,000 more employees this year that we cannot replace. We simply do not have enough staff to complete all of the work for which we are responsible, and we made strategic decisions about the areas in which we must do less with less.

Eliminating the hearings backlog remains our top priority. With the resources we received in FY 2012, we can still achieve our commitment to reduce the average hearings processing time to 270 days by the end of FY 2013 provided we are able to hire enough administrative law judges. It will be an extraordinary accomplishment because we have faced a significant increase in hearing requests due to the economic downturn.

While we cannot afford to complete the level of program integrity work authorized under the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) because Congress did not appropriate the full amount, we will increase the number of program integrity reviews that we conduct by 90,000 more full medical continuing disability reviews (CDR) this year.

I am pleased to report that our hard-working, dedicated employees continue to improve our efforts to prevent, detect, and recover improper payments. As a result, the Social Security program is the most accurate in the Federal Government. Our employees also are vigilant about protecting program dollars from waste, fraud, and abuse, and make referrals to our Office of the Inspector General (OIG) as appropriate. Our OIG has the agency lead for investigating cases of possible fraud and referring them for criminal prosecution and other penalties. We believe that our cooperative efforts with the OIG have resulted in an extremely low incidence of fraud in our programs. It is important to remember that not all overpayments are improper and not all improper payments are necessarily fraud. For example, beneficiaries whom we have determined have medically recovered have the right under the statute to request that their benefits continue while they are awaiting the appeal. While such continued benefits are not improper payments as they were correctly paid under the statute, if the appeal upholds our medical recovery determination, they are considered overpayments subject to recovery.

The Disability Programs We Administer and Our Payment Accuracy

Social Security touches the lives of nearly every American, often during times of personal hardship, transition, and uncertainty. Our 80,000 Federal and State employees serve the public through a network of 1,500 offices across the country. Each day, almost 180,000 people visit our field offices and more than 435,000 people call us for a variety of services such as filing claims, asking questions, and reporting changes in circumstances (including a return to work).

The two disability programs we administer are the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. The SSDI program protects against loss of earnings due to disability. The SSI disability program assists blind and disabled persons with limited income and resources. These two disability programs provided an average of 15 million beneficiaries with a total of approximately $175 billion in benefit payments in FY 2011.

Overall, our SSDI payments are highly accurate. Our most recent data show that, in FY 2010, 99.3 percent of all SSDI payments were free of an overpayment, and 99.0 percent were free of an underpayment. While we are proud of our high accuracy rate for SSDI payments, we recognize that our SSI overpayment accuracy rate falls short of that high standard. To a large extent, inaccuracy is inherent in the complex program rules and the delays in receiving income data. SSI payments can change each month due to income and resource fluctuations and changes in living arrangements. Our overpayment accuracy rate, though improving, reflects that complexity. In the SSI program, 93.3 percent of all payments were free of an overpayment, and 97.6 percent of all payments were free of an underpayment, a significant improvement from FY 2008.1

The Complexity of Our Disability Programs and the Causes of Payment Errors

Our disability programs are challenging to administer. Determining that an individual is eligible for SSDI or SSI benefits is a complex and generally time-consuming process. Under the SSDI program, we must evaluate an individual’s mental and physical impairments to determine whether the impairments are so severe that they prevent the claimant from engaging in work that exists in the national economy. In the SSI program, we apply the same standard for adults but we must also consider an individual’s often rapidly changing income and resources before awarding SSI benefits based on disability. When we consider a person’s continued eligibility for SSDI or SSI benefits, the law adds further complexity by requiring us to document medical improvement that relates to a person’s ability to work, a higher standard.

The leading cause of overpayments in the SSDI program is error in the application of substantial gainful activity (SGA). SGA refers to the level of a beneficiary’s work and earnings that can affect benefit payments.2 Beneficiaries are required to tell us if they return to work. However, because the statutory rules for return to work are complicated, beneficiaries are often unsure when they have to report work to us. Congress has created opportunities for beneficiaries to try to return to work. For example, under the SSDI program, beneficiaries can test their ability to work in a trial work period (TWP) without affecting their benefits. The TWP ends when a beneficiary completes 9 months with earnings over a threshold amount ($720 per month in 2012) within a rolling 5-year period. After the TWP, a beneficiary enters into the extended period of eligibility (EPE). The EPE is a 36-month period during which we pay benefits only in the months a beneficiary earns below SGA. Entitlement to benefits ends with the first month of SGA after the EPE. In many cases, beneficiaries fail to report that they have begun a TWP or have continued to work into the EPE. A beneficiary’s failure to report can lead to an overpayment.

Even when a beneficiary reports to us, we cannot always act immediately if the person is still working in a TWP. Determining whether a beneficiary’s work and earnings are SGA takes considerable time and requires delays while we get the additional information we need to make the determination. We must get information about the beneficiary’s return to work from the beneficiary or the beneficiary’s employer. Each year we must address large volumes of work reports, and there are inevitable delays in receiving and processing this supplemental information. Our work-related activities require a lot of starting and stopping work on a case while we develop the case, answer necessary questions, review it, and finally have the right information to take action. This work also requires expertise, and we need to have enough trained employees to complete it timely. The same employees who help the 45 million people who come into our offices each year must also handle this work. The longer it takes us to get to this work, the more likely the overpayment will be higher.

SSI has a different set of work rules. For SSI disability, SGA is a test to determine only initial eligibility rather than continuing eligibility. When an SSI disability beneficiary returns to work, we do not apply the SGA rules. Rather the law requires that SSI benefits be reduced by $1 for every $2 in earnings.

Improper payments often occur when beneficiaries fail to timely report changes, such as an increase in the value of resources or an increase or decrease in wages. Failure to report these changes is the primary cause of improper payments in the SSI program.

Given the complexity of the statutes governing our disability programs and the volume of work, some overpayments are unavoidable. The complexity of our return-to-work provisions is exacerbated when a beneficiary receives both SSDI and SSI, because the beneficiary is subject to two different sets of rules. For example, almost 30 percent of SSI beneficiaries aged 18-64 also receive SSDI.

The President’s FY 2012 budget included two proposals that have the potential to reduce disability program overpayments by testing programmatic simplification and giving us access to important State, local government, and private insurer benefit information.

The first proposal is the Work Incentives Simplification Pilot (WISP). We believe WISP could address a significant disincentive to work under the current SSDI rules: the fear of losing benefits due to work activity. The current set of work incentive policies and postentitlement procedures have become very difficult for the public to understand and for us to effectively administer. The goal of WISP is to conduct a test of simplified SSDI work rules, subject to rigorous evaluation protocols, that may encourage beneficiaries to work and reduce our administrative costs. WISP would eliminate complex rules on the TWP and EPE. It would also eliminate performing SGA as a reason to terminate benefits. Further, we would count earnings when they are paid, rather than when earned, which would better align the rules of the SSDI and SSI programs. If a beneficiary’s earnings fell below a certain threshold, we could reinstate monthly benefit payments as long as the person was still considered to be disabled.

The second proposal would require State and local governments and private insurers that administer worker’s compensation (WC) and public disability benefit (PDB) plans to provide us with information on WC and PDB payments. By requiring plan administrators to provide payment information to us promptly, this proposal would improve the integrity of the WC and PDB reporting process, improve the accuracy of SSDI benefits and SSI payments, and lessen our reliance on the beneficiary to report this information in a timely manner.

We urge Congress to consider both of these proposals. They hold significant promise to help us reduce improper payments in our disability programs and save taxpayer dollars.

Our Primary Program Integrity Tools

“Curbing Improper Payments” is the first objective under our 2008-2013 Agency Strategic Plan Goal to “Preserve the Public’s Trust in Our Programs.” When an individual applies for one of our disability programs, we have a system in place to ensure accurate decisions. Each year, we are statutorily required to review at least 50 percent of all State Disability Determination Services (DDS) initial and reconsideration allowances for SSDI and SSI disability for adults. Based on the results of these reviews in FY 2009—the most recent year for which data are available—the decision to allow or continue disability was correct in 98.9 percent of all favorable SSDI determinations and 99 percent of all favorable SSI disability determinations for adults. These reviews allow us to correct errors we find before we issue a final decision, resulting in an estimated $558 million in lifetime program savings, including savings accruing to Medicare and Medicaid. The return on investment has been roughly $11 for every $1 of the total cost of the reviews.

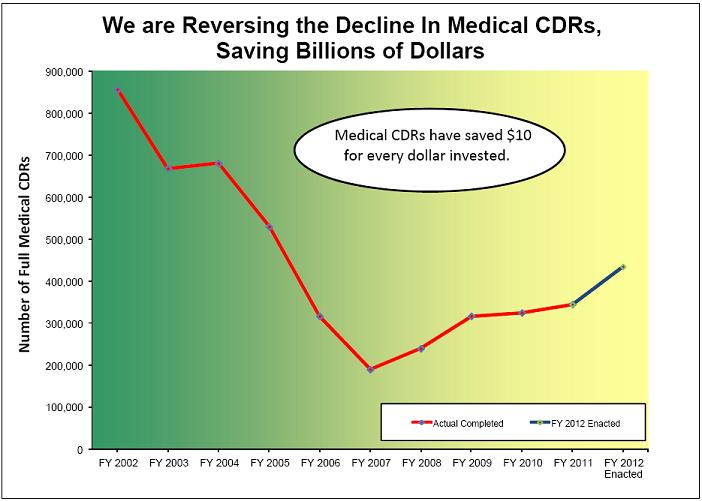

Once an individual is on the disability rolls, our primary program integrity tools are medical and work CDRs and SSI redeterminations. We periodically conduct medical CDRs to evaluate whether SSDI and SSI beneficiaries continue to meet the medical criteria for disability. We also conduct medical CDRs when we receive a report of medical improvement from a beneficiary or third party. We complete medical CDRs in two ways, which together ensure that we are targeting our resources to the most problematic areas in the most cost-effective way. The medical CDR process uses a statistical modeling system that uses data from our records to determine the likelihood that a disabled beneficiary has improved medically. If the statistical modeling system indicates that the beneficiary has a high likelihood of medical improvement, we send the case to the State DDS for a full medical review. The remaining beneficiaries who are due for review but have a lower likelihood of medical improvement receive a questionnaire requesting updates on their impairments, medical treatment, and work activities. If the completed mailer indicates that there has been potential medical improvement, we send the case to the DDS for a full medical review. Otherwise, we reschedule the case for a future review. To date since 1996, we estimate that on average each dollar spent on medical CDRs yields at least $10 in lifetime program savings, including savings accruing to Medicare and Medicaid.

We have shown that with adequate funding for medical CDRs, we are able to produce results. For example, in 1996 we received a 7-year commitment of special funds to conduct medical CDRs. By the time the funding commitment expired at the end of FY 2002, we had completed 9.4 million CDRs (including 4.7 million full medical reviews) and were current on all CDRs that were due. For all the medical CDRs completed during the period FYs 1996 through 2002, we spent roughly $3.4 billion, with an estimated associated lifetime savings from this activity of approximately $36 billion.

Unfortunately, from FY 2003 through FY 2007, inadequate funding forced us to reduce the volume of medical CDRs we completed, and, as a result, we could not keep up with all the CDRs that were due. In recent years, additional funding for program integrity has allowed us to increase the volume of full medical CDRs though not to the level that the President has recommended. Last fiscal year, we completed about 345,000 full medical CDRs, a 66 percent increase over the number we completed in FY 2007. Nevertheless, we still have a backlog of about 1.3 million medical CDRs. With full funding of the additional program integrity levels authorized under the BCA, we project that we could nearly eliminate the medical CDR backlog over the next decade, with the exception of SSI adult medical CDRs, which have the lowest return on investment. However, in FY 2012 Congress did not fully fund the BCA level of program integrity resources. Therefore, we will complete about 435,000 full medical CDRs, a significant increase over FY 2011 but 130,000 fewer than the number authorized under BCA. Given the historically high return on investment of medical CDRs, we believe that fully funding this workload is a smart investment.

Figure 1

A work CDR is a review of eligibility requirements regarding an SSDI beneficiary’s earnings

or ability to work. Work CDRs are triggered by reports of earnings from beneficiaries or

third parties, systems alerts, and earnings posted to a beneficiary’s record. For instance, after

an SSDI beneficiary completes a TWP and continues to work, we would conduct a work

CDR to determine if the beneficiary’s earnings preclude entitlement to payment. We may

also receive either a report of earnings or an earnings alert for unreported earnings. Our

Continuing Disability Review Enforcement Operation uses Internal Revenue Service

earnings data to identify possible work CDRs for SSDI beneficiaries. It generates about

600,000 alerts annually, and we target the alerts with the highest identified earnings and

work those cases first. In recent years, we have allocated additional staff resources to

analyze the work reports we get from all sources and to conduct more work CDRs. We are

also targeting the cases with the oldest work reports—those over 365 days old.

We handle work CDRs in field offices and processing centers. We use a program called

eWork to automate work CDR processing. eWork collects necessary data from mainframe

databases, prepares forms, notices, and work report receipts, incorporates policy and decision

logic, and adjusts benefits.

Despite our budget constraints, we have focused resources on completing more work CDRs

to minimize overpayments. In FY 2010, we completed 312,471 work CDRs.3 Of these,

105,279 resulted in a finding of cessation of disability, or a subsequent reinstatement or

suspension of benefits in the EPE. In FY 2011, we increased the number of work CDRs we

completed to about 324,000.4 While we are still finalizing our data regarding the outcome of

those work CDRs, we estimate that about 130,000 resulted in a finding of cessation of

disability, or a subsequent reinstatement or suspension of benefits in the EPE. This fiscal

year we are focusing our limited resources in a few key areas to reduce overpayments. We

are dedicating resources to ensure that we handle actions related to work more timely and

address overpayments quicker. Nevertheless, we simply do not have the resources to

complete all of these cases.

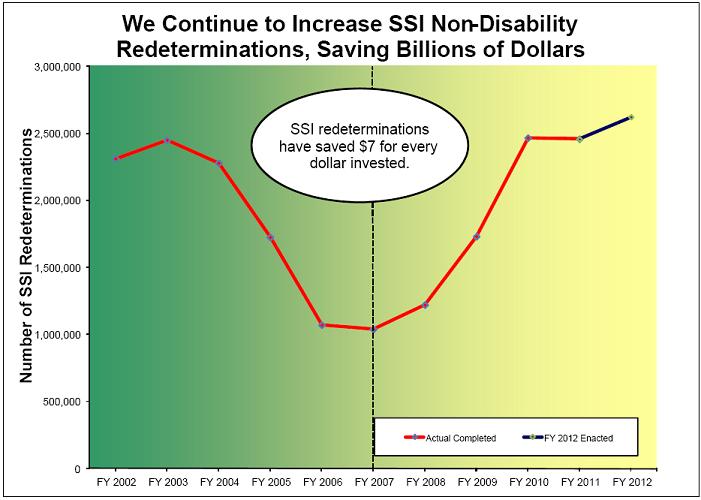

Redeterminations are reviews of all of the nonmedical factors of eligibility to determine whether a beneficiary is still eligible for SSI and still receiving the correct payment amount. We focus on the most error-prone cases each year using a statistical model. In FY 2011, this statistical model allowed us to prevent $1.4 billion more in overpayments than what a random selection of cases would have prevented. Historically, every dollar spent on SSI redeterminations returns more than $7 in lifetime program savings, including savings accruing to Medicaid.

Just like the number of medical CDRs from FY 2003 to FY 2007, the number of SSI redeterminations we conducted over the same period dropped precipitously due to inadequate funding. Compared to FY 2007, we are now completing about 1.5 million more SSI redeterminations each year due to increased funding for program integrity. We anticipate completing 2.6 million SSI redeterminations in FY 2012. The additional SSI redeterminations we have completed in recent years are the primary reason why we have been able to increase our SSI overpayment accuracy rate by 3.6 percentage points—a statistically significant amount—over the past 3 years.

Figure 2

The same employees who complete CDRs and redeterminations also have many other critical responsibilities, such as taking and adjudicating SSDI and SSI applications. While our workloads continue to grow and expand, the number of people to do the work has decreased.

Any workloads that we must defer due to inadequate funding—whether program integrity work or deciding initial claims—become only more complex and costly to complete the longer that the workload ages. For example, with a work CDR, we have to look at virtually every month over a specified period to determine if a person worked, the amount of his or her earnings, and whether the person had impairment-related expenses or special subsidies. If we do not get to the work CDR shortly after the person goes to work, we have more months in the period to analyze, more pay stubs to examine, and, generally, more variables to factor into our determination. As the time it takes to handle this workload increases, the likelihood of large overpayments in those cases also increases.

The President’s FY 2012 Budget included a legislative proposal to require employers to report wages quarterly. Increasing the timeliness of wage reporting would provide us more current information on our beneficiaries’ work activity, which could help to minimize the amount of overpayments. Reverting to more frequent wage reporting would enhance program integrity in a variety of programs.

In the past few years, we have developed and rolled out two initiatives further that improve our SSI accuracy rates. Those initiatives are the Access to Financial Institutions (AFI) project and the SSI Telephone Wage Reporting (SSITWR) system.

AFI is an electronic process that allows us to identify financial accounts of SSI applicants and beneficiaries that exceed statutory limits. As of June 2011, all 50 States use AFI, and we achieved this goal 3 months ahead of schedule. We will soon complete systems enhancements that will further automate the AFI process.

The AFI project has proven very useful in identifying undisclosed accounts. For example, just last summer, we had a case in which a claimant stated he had a bank account under the $2,000 SSI limit. The actual account balance verified through AFI was $200,000. In another case, a claimant said he had only one bank account under the resource limit. Using AFI to contact multiple banks, we uncovered six bank accounts with balances of nearly $25,000 in each account. We are looking at the possibility of expanding this successful program to real property.

SSI beneficiaries can report wage data through the SSI Telephone Wage Reporting (SSITWR) system, which automatically processes the wage information into the SSI system. In FY 2011, we processed more than 325,000 monthly wage reports using this system. These reports generally are accurate and require no additional evidence, which saves time in our field offices. SSITWR has allowed us to increase the volume of wage reports we receive, and therefore reduces wage-related errors.

We are also expanding our marketing of this service to the public. This fiscal year, we expect to conduct a targeted outreach to representative payees of working SSI beneficiaries, a population that has successfully adopted SSITWR in prior testing.

Data Exchanges and Other Systems Enhancements

We rely on data exchanges to help us protect the integrity of our programs. Efficient, accurate, and timely exchanges of data promote good stewardship for all parties involved. We have over 1,500 exchanges with a wide-range of Federal, State, and local entities that provide us with information we need to stop benefits completely or to change the amount of benefits we pay. We also have about 2,300 exchanges with prisons that allow us to suspend benefits to prisoners quickly and efficiently.

Data exchanges are also a cost-effective way to prevent and detect improper payments. For example, in FY 2008, for every dollar spent on our pension match with the Department of Veterans Affairs, we saved nearly $39 in SSI benefits. Similarly, during the same timeframe, every dollar we spent on our match with Office of Personnel Management saved us almost $20 in Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) benefits.

We also depend on advanced technology to help balance the need to keep up with growing workloads and to be effective stewards of the Social Security Trust Funds and taxpayer dollars. Technology and automation are keys to providing quality service to the public as our workloads continue to grow. For example, we recently introduced systems enhancements to the Returned Mailer System (RMS), which tracks the status of a medical CDR mailer from release until we receive a response from the beneficiary. The enhancements included implementing text-mining software that scans the mailer responses for keyword matches, thereby eliminating the manual handling of mailers that meet certain criteria. In those cases, the RMS decides the appropriate action to take (full medical CDR, manual review of the mailer response, or no further action), thus expediting decisions.

Tools to Recover Overpayments

In addition to our efforts to prevent improper payments and improve our payment accuracy, we also have a comprehensive debt collection program. We recovered $3.2 billion in program debt in FY 2011 and $14.72 billion over the previous 5-year period (FYs 2007- 2011) at an administrative cost of $.08 for every dollar collected.

We recover OASDI and SSI overpayments from overpaid beneficiaries and representative payees who are liable for the overpayment. To recover debt, we withhold current benefit payments from the debtor. It is harder to recoup a debt once benefits end; therefore, we make every effort to identify and collect debt as soon as possible. If the overpaid person no longer receives benefits, we offer the opportunity to repay debt via monthly installment payments.

When we cannot recover a debt on our own, we turn to authorized external debt collection tools. These tools include:

• Tax Refund Offset;

• Administrative Offset (collection of a delinquent debt from a Federal payment other

than a tax refund);

• Credit Bureau Reporting;

• Administrative Wage Garnishment;

• Non-Entitled Debtors Program (a system that facilitates recovery of debt owed by

non-beneficiaries, such as representative payees); and

• Federal Salary Offset.

We plan to improve our debt collection programs by implementing several enhancements to allow us to take advantage of changes in the law that expand the availability of administrative offset. For example, we will make systems changes to allow us to collect delinquent debt via the Treasury Offset Program beyond the current 10-year statute of limitations. The Department of the Treasury removed the 10-year limitation to collect delinquent debts via the program and we amended our regulations in October 2011 to conform to this change. As resources permit, we will start using other existing debt collection authority such as private collection agencies, charging administrative fees and interest, or indexing a debt to reflect its current value.

In providing us with these debt collection tools, Congress recognized that maximum debt collection is not the only consideration. We must balance our stewardship responsibilities with compassionate recognition of our beneficiaries’ individual situations. For example, the law limits us to withholding no more than 10 percent of an SSI beneficiary’s monthly income to recover an overpayment. Reducing the already minimal SSI payment too much could leave the beneficiary without enough money to meet basic living expenses. Similarly, the law prohibits recovery of overpayments from any beneficiary who is without fault if the recovery would defeat the purpose of the programs or be against equity and good conscience.

However, we are considering regulatory changes that could potentially allow us to collect more of our programmatic debt. Such regulatory changes could include increasing the minimum monthly repayment amount for certain beneficiaries with overpayments.

Our Cooperative Efforts with OIG

We work with our OIG to operate investigative units—called Cooperative Disability Investigations (CDI) units—across the country. Each unit consists of an OIG special agent, State or local law enforcement investigators, State DDS examiners/analysts, and our management support specialists or similar employees. Our CDI units allow us to more quickly determine whether fraud has potentially taken place and move forward with deciding disability claims if we are satisfied that fraud has not occurred. By fostering an exchange of information between disability decision-makers and the CDI units, the CDI program increases our ability to identify and prevent overpayments, as well as deny potentially fraudulent initial applications. The program also ensures timely investigation and the termination of benefits when we detect fraud during work or medical CDRs.

CDI units also investigate and support criminal prosecution of doctors, lawyers, and other third parties who commit fraud against the SSDI and SSI disability programs. The results of these investigations may also be presented to Federal and State prosecutors for consideration of criminal or civil prosecution, as well as to the Office of the Counsel to the Inspector General for the possible imposition of civil monetary penalties.

There are currently 25 CDI units operating throughout the United States, with a 26th unit expected to be operational before the end of this fiscal year. According to our OIG, since the program’s inception in FY 1998 through September 2011, CDI efforts nationwide have resulted in $1.8 billion in savings to our disability programs and $1.1 billion in savings to non-Social Security programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid.

These monetary achievements are the result of CDI units opening more than 34,700 cases and developing evidence to support approximately 26,270 actions, resulting in a denial, suspension, or termination of disability benefits.

In cases where Federal prosecutors would be otherwise unable to take action on fraud cases referred by the OIG due to resource constraints, our agency attorneys may prosecute these cases in Federal court instead. These attorneys serve as a Special Assistant to a United States Attorney’s Office in eight of our regional offices. There are a total of nine attorneys who take on these cases. From FYs 2003 through 2010, our attorneys secured over $36.9 million in restitution orders and 717 convictions or guilty pleas. In FY 2011, we secured nearly $6.8 million in restitution orders and 97 convictions for identity theft, program fraud, and Social Security number misuse.

The law provides a wide-range of penalties for individuals who make false statements, or who misrepresent or omit material facts used in determining eligibility for, or the amount of, OASDI or SSI benefits. We train our field employees to alert OIG to any cases of suspected fraud. We made nearly 19,000 such fraud referrals related to our disability programs in FY 2011, from which the OIG opened about 4,600 cases.

Conclusion

We take pride in our ability to protect and carefully manage the resources, assets, and

programs entrusted to us. We have earned the public’s trust, and we intend to do everything

we can to keep it. We are firmly committed to sound management practices, including using

accurate metrics for evaluating our programs’ integrity, and following up with appropriate

enforcement and recovery actions. We know the continued success of our programs is

inextricably linked to the public’s trust in them. Properly managing our resources and

program dollars is critical to that success.

We also know that congressional support is vital. In order to complete all of the work for

which we are responsible, we need Congress to fully fund those workloads in future

appropriations cycles. We are doing what we can to target our program integrity efforts to

areas that provide the best value, but we need adequate and timely resources to balance this

work with the increasing demand for our services.

_____________________________________________

1 These data include all categories of SSI beneficiaries.

2 Generally, earnings averaging over $1,010 a month (in 2012) demonstrate an individual’s ability to perform SGA. This amount is subject to modifications and exceptions based on other statutory incentives designed to encourage work, such as impairment-related work expenses, subsidies, and special conditions.

3 Because we reviewed some beneficiaries more than once during the fiscal year, the number of completed work CDRs involves about 264,000 SSDI beneficiaries.

4 The number of completed work CDRs for FY 2011 likely includes some beneficiaries for whom we completed reviews more than once.