Arthur J. Altmeyer

Never A Finished Thing: A Brief Biography of Arthur Joseph Altmeyer--The Man FDR Called "Mr. Social Security"

by Larry DeWitt

SSA Historian

1997

|

Arthur Altmeyer was one of the seminal figures of the

Social Security program in America. He was part of the President's

Committee on Economic Security that drafted the original legislative

proposal in 1934. He was a member of the three-person Social Security

Board created to run the new program, and he was either Chairman of

the Board or Commissioner for Social Security from 1937-1953. Although

he believed that public administration was a vitally important activity,

he was also one of the principal conceptual and philosophical spokesmen

for social insurance in America, and much of the policymaking during

Social Security's founding decades was formulated by Altmeyer. Along

with a mere handful of others, Arthur J. Altmeyer is responsible for

the Social Security program as it exists in America today. This biography attempts a very brief, broad-brush overview of Altmeyer's life and his contributions to Social Security. It is a work in progress. The full story of the central role of Arthur Altmeyer in the history of Social Security is a story that remains to be told. |

| Chapter 1: Early Life | ||||||||||

|

"Social Security will always be a goal, never a finished thing, because human aspirations are infinitely expandable, just as human nature is infinitely perfectible." -- Arthur J. Altmeyer Altmeyer was born in the little town of DePere Wisconsin, near

Green Bay. His father was of German ancestry, the Altmeyers having

come to American in 1848 with the wave of German immigration seeking

to escape the reactionary political climate in the Germany of

that period. So he inherited, you might say, a liberal progressivism

in his genes. His mother was Dutch.

|

||||||||||

| The "Wisconsin World View" Unquestionably, one of the most powerful formative experiences of Arthur Altmeyer's life was his education at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, at the knee of the renowned economist John R. Commons, in the intellectual center of a world-view that we might call the "Wisconsin World View." The Wisconsin World View, broadly construed, was a liberal social policy tradition, emphasizing a positive and vigorous role for government. Commons was a "labor economist" and was the principal author of Wisconsin's first-in-the-nation Workmen's Compensation program. Not only did Altmeyer study under Commons as an undergraduate, but he returned to Wisconsin in 1918 (four years after his graduation) to become Professor Common's assistant.

Altmeyer's interest in social policy and labor legislation was awakened by a chance reading of a pamphlet on Wisconsin's pioneering workman's compensation program. The Wisconsin law had just passed in 1911 when Altmeyer was beginning his college studies. "The first big wave of social insurance and labor legislation was on then," Altmeyer later recalled. Prof. John R. Commons of the University was an industrial commissioner. I remember getting that pamphlet explaining the workman's compensation law. I read it and got interested in it, and decided that I was going to go under Professor Commons and study labor legislation." So Altmeyer's world-view was shaped by his father's liberal background, the general progressivism of Wisconsin in the early years of the century, and by his tutelage at the knee of John R. Commons. These forces, and no doubt others, combined to give Altmeyer a life-long, deeply-held, commitment to the cause of social welfare.

Of Stern Stuff Altmeyer was a serious, even stern fellow. One biographer described him as "Scholarly, spectacled Arthur J. Altmeyer is. . . an earnest man, not given greatly to humor."As an administrator he would seek anonymity, believing that able and efficient administration did not require self-promotion. A newspaper profile in 1939 would be headlined: "Security Board Chief Likes Obscurity." Altmeyer would put the matter plainly: "A successful administrator is about as interesting to the public as cold spinach."

Altmeyer was also a man of unusual modesty for someone of his stature and achievements. One story illustrates both his modesty and his dedication to the Social Security program. Altmeyer was Chairman of the Social Security Board from 1937-1946, and Frank Bane was the Executive Director (sort of the chief operating officer). Bane was the number four official at the Social Security Board, after the three voting members. Altmeyer's primary skills and talents were in administration and Bane's were in public relations--a reversal of their actual job assignments in some ways. Bane was gregarious and outgoing and had political connections everywhere. Altmeyer was scholarly and reserved, preferring policy analysis to politics. In 1938 Bane had an opportunity to leave the Board to become the head of the Council of State Governments. When he told Altmeyer he was leaving to accept the new position, Altmeyer offered to switch jobs with him on the spot if Bane would stay. Altmeyer knew Bane was invaluable to the work of the Board and he was willing to take a demotion and cut in pay and go to work for his former subordinate if that would persuade him to stay. When commenting on this incident, the executive secretary of the Board, Maurine Mulliner, would observe: ". . . it's an indicator of the modesty of Arthur Altmeyer. Some people, having received a 'no' from him in response to some request, have interpreted it as being aloofness, stand-offish. Generally, I think it is this excessive modesty. He really has a high degree of humility and personal modesty that's unusual in a man in public life in the roles he has carried."

The Wisconsin Period After graduating from college in 1914, Altmeyer became a school teacher in northern Minnesota. After two years he moved up to the job of principal in Kenosha, Wisconsin. As soon as he paid off his college debt of $1,200 he gave up his job and returned to the University of Wisconsin to do graduate work and to take a part-time position as John Commons' research assistant. Because his part-time job paid only $400 a year, he had to take a second part-time job as a statistician with the Wisconsin State Tax Commission. (His wife got a teaching job in Madison and became thereby the first married woman allowed to hold a full-time teaching job in the history of that city.) Commons was an inadvertently demanding task master who thought nothing of tasking his young assistant with assignments that consumed a full eight-hour day. As Altmeyer described this period: ". . . I discovered that Commons had no idea of the amount of effort required to carry out an idea of his, and he had many many ideas every day. . . So instead of working one-fourth time, I'd say I worked more than eight hours a day on work for Professor Commons. I worked down at the State Tax Commission. . . from about 8 till 12. So there were 12 hours, I'd say, out of the day. Then I was taking full time graduate work. I had to do that at night, and I recall many times I'd tumble into bed at maybe 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning." Thankfully, Edwin Witte, who was Secretary of the State Industrial Commission, saved Altmeyer from exhaustion by offering him a full-time job as the Commission's Chief Statistician. Three years later, Witte left to become the Chief of the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Library and Altmeyer was promoted to replace him. This was the job he would hold until Frances Perkins summoned him to Washington, the first time in 1933, and then again in 1934. |

||||||||||

| Chapter 2: To Washington, An Earnest "New Dealer" | |||

|

As Secretary of the Industrial Commission Altmeyer spent a lot of time in Washington, especially during the early years of the Depression, seeking various kinds of federal help for Wisconsin. Altmeyer said of this period, "I started coming down to Washington with my hat in one hand and a tin cup in the other." Through these and other professional efforts he came to be known at the Department of Labor and in early 1933 Frances Perkins asked him to come to Washington temporarily to help her with her initial reorganization of the Labor Department. As soon as this task was completed, Secretary Perkins persuaded him to stay on for a while as the Labor Department's representative with the National Recovery Administration. Officially, he was Assistant Compliance Officer, overseeing the enforcement of the various industry codes related to labor. After about six months of this, Altmeyer decided it was time to return to Wisconsin, to his permanent job at the Commission--from which he had taken a leave of absence. He previously had told Secretary Perkins that he needed to return to Wisconsin, and when the time came to leave he went to see her to say goodbye, but she was not in her office. He boarded the evening train for Madison and when he arrived he found a telegram from Perkins waiting for him. She wanted him to return immediately. He hopped on the return train and when he got back to Washington Perkins offered him a permanent job as Assistant Secretary of Labor. Even before taking the oath as Assistant Secretary in June 1934, Altmeyer was commuting back and forth between Madison and Washington and was doing important work for the Secretary. He authored the famous message from FDR to the Congress in which the President promised to present a new proposal for economic security when the Congress returned from recess in January 1935. It was this message that led to the creation, by Executive Order, of the Committee on Economic Security that would lead, in barely more than a year, to the Social Security Act. The June 8, 1934 message was thus the foundation document of Social Security in America, and Arthur Altmeyer, soon-to-be Assistant Secretary of Labor, was its author.

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Chapter 3: Creating the Social Security Act | |

| The Committee on Economic Security The Committee on Economic Security (CES) was created by President Roosevelt three weeks after Altmeyer's message to the Congress. Frances Perkins was named the Chairman, with her cabinet colleagues as the other members. The Executive Order (which Altmeyer also wrote) also established an Advisory Council (which would play virtually no role); an Executive Director; and a Technical Board. Perkins instantly named Altmeyer as Chairman of the Technical Board, and Altmeyer selected his old boss, Edwin Witte, to be Executive Director. It was the CES that designed America's Social Security program, starting virtually from scratch, and completing its work in barely six months. Not only did CES design the program, but the numerous technical studies it produced served as a foundation for legislation and initial policymaking and in providing the raw data needed to support the Supreme Court's ruling on the Act's constitutionality. As Chairman of the Technical Board, it was Altmeyer, along with Edwin Witte and Frances Perkins who were the principal players on the CES. These three individuals shaped, in the large, the Social Security program that emerged from the CES' work (along with the broad guidance provided by President Roosevelt--which proved critical at a couple of important junctures). FDR, Altmeyer, Perkins and Witte. If we wanted to establish the Hall of Fame for Social Security, these would be the first four names. |

| Chapter 4: Putting the Act Into Operation | |||||||

|

The Board consisted of three members: Altmeyer; former Governor John Winant of New Hampshire as Chairman; and Vincent Miles, an Arkansas politician. By far the most important of these three was Altmeyer. It was Altmeyer who was the major policy maker and the only administrator of the three. It was Altmeyer, along with the Board's Executive Director, Frank Bane, who really ran the new agency in the early years. And when Winant resigned as Chairman early in 1937 Altmeyer replaced him. The Board was abolished in 1946 when the Social Security Administration (SSA) was created and Altmeyer became SSA's first Commissioner. So Altmeyer was the head of Social Security, in one capacity or another, from February 1937 until April 1953. |

|||||||

|

Altmeyer & The Character of SSA Many people think that being in power in government means making public policy. Altmeyer believed as a bedrock conviction that administration was his most important duty and the most important duty of his Agency. And he thought administration was an important skill and contribution in itself. His motto was an expression of Commons' who often said "administration is legislation in action." Much of the success of SSA over the years, and its reputation as the best agency in the federal government, was due to Altmeyer's insistence on the importance of fair, efficient and unbiased administration. He established the firm position that the Agency would be staffed by career civil servants, hired on merit rather than political patronage. In fact, the SSB was the first large federal agency staffed based on this principle. And keeping politics out of the administration of Social Security was no easy task. One U.S. Senator importuned the Board to hire someone he recommended. Since the person was unqualified for the position, Frank Bane, the Board's Executive Director, refused. Whereupon the Senator had a rider attached to the Board's annual appropriation that, by law, cut Frank Bane's salary by $500 (this was a bit more than 5% of Bane's annual salary). Such was the price that the Board had to pay to keep politics out of program administration. Because he was so concerned with integrity, and so concerned with blocking patronage appointments, Altmeyer and Winant personally reviewed each field office manager selection in the first years of the program. Wilbur Cohen, who was Altmeyer's personal assistant in the early years, tells of coming into Altmeyer's office and finding Altmeyer and Winant down on the floor with 3X5 index cards spread all around. On the cards were the names of all candidates for office managers and Altmeyer and Winant were personally making the job selections. Altmeyer was also the one who defined and institutionalized the ethic of public service that characterizes the administration of the Social Security Act. From the earliest days of the program, the Agency has held to an explicit philosophy of service to the public premised on Altmeyer's core belief that the Agency has an affirmative obligation to assist applicants in securing all the benefits to which they are entitled. This philosophy of service was revolutionary in its time and the Social Security Board was the first government agency to adopt such an approach to its duties. Indeed, this philosophy of service was highly controversial. The General Accounting Office (GAO) raised strong objections, pointing out that an obscure 1835 law says no federal official "shall encourage a claim against the federal government or assist in its prosecution." According to GAO, Altmeyer and the Social Security Board were in violation of this law. Altmeyer argued at length that this was not the case and that since the Social Security Act established an entitlement to these benefits, the Agency had an obligation to help applicants secure the benefits to which they were entitled. In addition to articulating the Agency's ethic of service, Altmeyer also made sure that this philosophy was instilled into each and every employee. Up until the late 1960s, every new employee of Social Security was brought to Baltimore for an extended training program, which not only taught them the technical aspects of their new jobs, but inculcated the history and philosophy of social insurance and the ethos of public service espoused by the Agency. Altmeyer would later say of this training and indoctrination:

|

|||||||

| Chapter 5: Mr. Social Security | ||||

|

"Mr. Social Security" Even though he prided himself and his organization on administration, Altmeyer was also the premier policy maker of his era. From the earliest days of the program, he was a spokesman for social insurance in America and was the primary "evangelist" (a description he would have hated) for convincing the nation of the value of this new experiment in social welfare policy. He often articulated Social Security policy in larger contexts, as part of a social welfare tradition with old roots and based on eternal truths about human nature. He was very much a "big picture" thinker. He also was, despite his stated alliance to administration, a master legislative craftsman. The improvements to the Social Security program embodied in the 1939 Amendments, and especially in the 1950 Amendments, were to a considerable degree the realization of Altmeyer's legislative agenda. Indeed, if you read the speeches and articles reproduced here that Altmeyer authored throughout the late 1930s and the 1940s, he lays out in great detail the policies and proposals that are destined to become law during the next couple of decades.

Altmeyer and the Development of Social Security Altmeyer argued tirelessly for many core ideas that would not

be realized until long after he left office--and some that to

this day remain unfulfilled dreams. He argued for coverage of

permanent disabilities and health care needs, and his vision would

be realized in the 1956 Amendments and in the creation of Medicare

in 1965. He argued for universal coverage of all workers, and

this goal is still not quite yet in hand. He argued also, for

a philosophy of social welfare that viewed all forms of social

insurance in equal terms. He viewed all forms of public provision

as part of a hoped-for comprehensive system, with appropriate

forms of provision--by social insurances or by public assistance

as need be. He asserted that unemployment insurance could be better

run as a federal program. And he pleaded for more generous benefits

for virtually all social welfare programs. Most of this agenda

remains unrealized. The "Missing Pieces" of Social Insurance The advocates of social insurance wanted the original Social Security Act to include comprehensive programs for the major threats to economic security, including death, disability, illness, unemployment and retirement. The 1935 Act did not include sickness or disability benefits or survivors benefits and was thus seen by these theorists has having "missing pieces." This was certainly Altmeyer's view. Therefore, almost before the ink was dry on the 1935 Act, Altmeyer began to campaign for the extension of Social Security to include these other forms of coverage. In a January 1943 radio address Altmeyer offered what we can take as a definitive statement of his vision of Social Security: " I believe that we should be thinking in terms of developing for this country a unified comprehensive system of contributory social insurance which would cover all of the major economic hazards to which the workers of this country are subjected, namely, old age, disability, death, and unemployment. We already have a Federal system providing protection against old-age and premature death and a Federal-State system providing some protection against unemployment, but we have no nationwide system providing protection against the hazards of ill health and disability. Under a unified comprehensive system of social insurance there would be no gaps, no overlaps, and no discrepancies in the protection afforded. Such a system could operate with a maximum degree of simplicity and efficiency. . . The present Federal old-age and survivors insurance central record system, which already contains 68 million individual accounts, could be used for all insurance purposes. . . The nationwide network of offices of the Federal old-age and survivors insurance system and the offices of the United States Employment Service could be merged and used as the offices of the new system. The contributory social insurance system should of course be extended to all employees and (except in the case of unemployment and temporary disability) should be extended to all self-employed persons as well. If this were done, we would be providing a minimum basic security for the people of this country upon which they would have a greater opportunity to build a higher degree of security through individual savings and private insurance. In other words, this minimum basic security would constitute a safety net protecting the workers of this country against these major economic hazards, not a feather bed releasing them from the necessity of helping themselves. While I believe responsibility for the establishment and maintenance of a unified comprehensive system of social insurance should be centralized in the Federal Government, I believe that the actual administration of the system should be highly decentralized with representative advisory committees and appeals councils in the several States. The cost of providing this basic security would not be excessive. If the cost were shared equally by employers and employees, contributions at the rate of 5 or 6 percent each would be sufficient for a long time to come. In my opinion such a plan would provide a maximum degree of protection to the people of this country at a minimum cost which could easily be borne because it would be spread evenly." At first he was cautious in pursuit of this vision. In his first public pronouncement after becoming Board Chairman, he would only say that the Board was "studying" the question of expansion of the program. "No one realizes more clearly than the Social Security Board that possible amendments now under consideration represent only the first beginnings in a long slow process of growth and development. . . There is no responsibility which it takes more seriously than the duty, placed upon it by the act itself, of studying and making recommendations to Congress, not only within the scope of the present act, but also in the whole field of social security legislation. Because it . . . believes profoundly that no program of social legislation is ever complete or final--that, indeed, in social legislation to "finish" would be to fail --the Board has no sense of apology either for the Social Security Act in its present form or for the admission that it is open to amendment." It was not until the summer of 1938 that he ventured for the first time to actually identify the specific shortcomings of the Act and the kinds of Amendments he had in mind, suggesting: survivors benefits, universal coverage, accelerated monthly benefits, and some acknowledgement of the need for disability and health coverage. This was, by no coincidence, the agenda he was pushing with the 1937-1938 Advisory Council. The Advisory Council was Altmeyer's first real opportunity to focus the nation's agenda on the "missing pieces." This Council, which Altmeyer initially opposed, would in fact become the vehicle through which Altmeyer would realize a major part of his vision. Altmeyer crafted a completed legislative agenda for the Council, persuaded President Roosevelt to support it, and skillfully "sold" it to the Council. The Council's report, which tracked Altmeyer's agenda almost perfectly, would become the very important 1939 Amendments, which fundamentally altered the nature of the program by adding survivors and dependents benefits to what had been a retirement program for workers. This changed Social Security from a program focused on the economic security of the individual worker and made it a program focused on the economic security of the family unit. This was very much in keeping with Altmeyer's vision of social insurance, and he played a major role in the development of the 1939 Amendments. After the passage of the 1939 Amendments Altmeyer's efforts shifted to disability and health insurance, as well as the overall adequacy of old-age insurance. The next big milestone was the 1950 Amendments. It was these amendments which increased the value and importance of old-age insurance and made it into the modern Social Security program we know today. If the theme of the 1939 Amendments was new benefits, the theme of the 1950 Amendments was benefit adequacy. Prior to the 1950 Amendments there were more recipients of old-age assistance than of Social Security retirement and the dollar amount of this public assistance was actually higher on average than the Social Security benefits. If this trend had not been reversed, there is good possibility that Social Security may well have been replaced by a welfare program. Indeed, years later, another Commissioner of Social Security, Bob Ball, would observe: "It is probably no exaggeration to say that the 1950 Amendments really saved the concept of contributory social insurance in this country." Again, Altmeyer was in a position to influence the legislation. By now, the big issues were coverage and adequacy, as well as disability insurance. The Administration recommended both significant increases in coverage and dramatic increases in benefits (both of which were enacted) and disability benefits (which were not). Altmeyer withheld any proposals regarding health insurance or unemployment insurance as battles to be fought another day. He was gratified that coverage and adequacy were addressed, and disappointed that disability was not. When Altmeyer left office in April 1953, two big pieces of his vision were still missing--disability benefits and health insurance. Recall that he had begun advocating both of these programs as early as 1938, and he took every opportunity to make the case that they were sorely needed. In the lead article of the March 1941 Social Security Bulletin, Altmeyer offered a detailed proposal for how a disability program might work--including thing from making disability determinations to computing benefit amounts. It was, in effect, the blueprint for a future disability program and most of this blueprint would be realized in 1956 when President Eisenhower signed the disability program into law. On health insurance neither Altmeyer nor anyone else conceived

in advance the unexpected way that health care would finally become

part of the Social Security Act--as a program, initially, only

for retirees. Altmeyer always conceived of health care coverage

as a universal need and it would never have occurred to him to

limit it to only one segment of the population. Of course, the

idea of limiting Medicare to the elderly was more a political

decision than the expression of a public policy principle. So

it should not come as a surprise that Altmeyer did not foresee

it. In any case, he did identify health care as a need early on,

he articulated its logic, and he advocated for it whenever he

had a chance. He even participated in the drafting of the famous

1945 proposal by President Truman calling for national health

insurance. But the realization of this part of the dream was many

years in the making. Universal Coverage Altmeyer and Frances Perkins, along with most all of the social insurance theorists on the CES, believed that the Social Security program should be nearly universal--so that all might share in its support and all might enjoy its benefits. After some modest internal debate, the CES did in fact settle on more or less universal coverage (the self-employed and highly paid professional were to be the only excluded groups). Their initial report, implicitly agreed to by President Roosevelt, was forwarded to the Congress with this recommendation and Altmeyer was deeply disappointed when the bill that emerged covered less than half the nation's workers under the new contributory social insurance scheme. Arguing for expansions of coverage thus became one of Altmeyer's earliest and most persistent "crusades." In only the second article he wrote for the Social Security Bulletin, in August 1938, Altmeyer could confidently observe: "In principle, there is no reason why old-age insurance should not apply to every wage earner and even to those who are not technically wage earners but who are the operators of small enterprises, that is, the 'self-employed.' Because of the practical administrative difficulties involved, this is an ideal which probably cannot be attained immediately. There is every reason to believe, however, that it will not be long before a number of wage earning groups, now excluded, will be brought into the system." Altmeyer was somewhat over-confident in this early assessment.

It would be 1950 before any significant inroads were made on his

goal of universal coverage. The reference to administrative difficulties

was due to the fact that this was the argument advanced by the

Treasury in 1935 for excluding certain groups from the program--Treasury

was afraid it would be too difficult to collect the taxes. But

this would prove to be one of Altmeyer's more successful "crusades"

in that the nation has in fact progressed steadily toward his

ideal of universal coverage--no doubt more slowly than he would

have liked. Universal Coverage--High Stakes Poker Henry Morgenthau, Jr. was FDR's second choice for Secretary of the Treasury. His first choice, William Woodin, died less than a year after taking office. Despite being FDR's second choice, Morgenthau had ready access to the President and often was able to influence him to support the policies Morgenthau preferred. The affinity between Morgenthau and FDR was based on a long-standing personal friendship--he was a Hudson Valley neighbor to FDR's magnificent Hyde Park estate, and they were "poker buddies" in the frequent games Roosevelt held with his closest circle of friends. Within the CES, the question of the scope of the program was settled in favor of universal coverage, which meant that essentially all employees in the country would be subject to the new payroll taxes and would eventually be eligible for the new benefits. Morgenthau signed the unanimous report to this effect. But when the legislative dust settled, the new Social Security Act would exclude from the program the self-employed, government workers, agricultural and domestic workers, members of non-profit, religious and charitable organizations, and all workers age 65 and older--hardly the universal coverage the CES proposed. The CES' legislative proposal had to be revised at the last minute to make the old-age insurance program fully self-supporting and this required actuarial recalculations of the tax and benefit rate tables included in the original proposal. These revised calculations were not available when the bill was first filed and had to be added by a later amendment. Once the revised rate tables were ready, a special hearing was held before Ways and Means to present them, and Secretary Morgenthau was the designated Administration spokesman. And in a time-honored tradition of Washington hard-ball politics, Morgenthau used the opportunity of his testimony to announce that the Treasury Department did not support universal coverage, citing administrative difficulties in collecting payroll taxes from certain types of workers. Secretary Perkins was angered by Morgenthau's move and spoke at the hearing in favor of universal coverage, but the Committee was only too happy to go along with the Morgenthau recommendations since this was the path of least political resistance. And because of this moment of high-stakes political poker, the new Social Security program would only cover about half of the nation's workers when it began in 1937. The biggest expansion in coverage was enacted in the 1950 Amendments, but even today the Social Security program has not quite achieved the universal coverage that the CES envisioned.

Public Assistance vs. Social Insurance One of Altmeyer's losing battles was his campaign to convince America that public assistance should be greatly expanded. Public assistance was woefully inadequate, he repeatedly said, and needed to be substantially raised. It made moral sense, he argued, it made economic sense, and it made public policy sense. In virtually every speech he gave or article he penned, Altmeyer returned again and again to this theme. He wanted America to adopt a comprehensive view of social provision whereby government protected its citizens against economic hazards by a combination of contributory programs where possible and "welfare" programs where necessary. But he did not view recourse to a welfare program as a failure in any sense. It was just that non-contributory forms of social insurance made more sense for certain groups of people, such as dependent children and chronic "unemployables." The stigmatizing of welfare as a moral failure of the recipient was alien to Altmeyer's philosophy, although he always viewed income from work as the basis for economic security. Thus, welfare was to be paid to people who suffered a disruption in their income "for reasons beyond their control," and who could not otherwise be provided for under social insurance programs. Although Altmeyer's views were fairly standard among the social welfare types of his era, they were considerably more liberal than the general attitude of the country at the time. They were conservative, however, in the sense that he always conditioned his advocacy of public assistance on the idea that people suffered from disruptions to their income for reasons other than choice--age, youth, illness and unemployment being the principal ones. He probably would have shared the common attitude that the able-bodied ought to work, and he viewed the creation of a "full employment" economy as one of the obligations of government--so that the able-bodied would have work to do. In one sense, Altmeyer's views were again ahead of his time in that during the "war on poverty" of the 1960s his more liberal view of welfare gained favor with the policymakers of that era. But this view, and the whole war on poverty, came to grief over an older, deeper, tradition in America--the idea that welfare was shameful and that the poor ought to be responsible for lifting themselves out of poverty, that their predicament was almost certainly their own fault. This quintessentially American attitude toward welfare was something Altmeyer could never overcome. And yet he tried, with practical argument and deeply held moral conviction. In 1952 he would optimistically observe: "A new concept of social welfare has been developing

under which welfare programs consist not only of counseling and

assisting the individual and family in making the necessary adjustments

to the environment but, more importantly, of marshaling community

resources to promote the well-being of individuals and of families

generally. In other words, we no longer think in terms of a few

underprivileged and disadvantaged persons but in terms of all

individuals and families. In this country, under this newer concept,

social work would include both constructive welfare services and

measures designed to promote economic security--that is, both

public assistance and the social insurances. . . In other words,

social security would be part of social welfare in its present-day

meaning." Federalizing Unemployment Insurance One of Altmeyer's biggest failures was his attempt to persuade the Congress and the States that the nation would be better off with a federal take-over of the unemployment insurance program. When the CES was considering its unemployment program recommendations there was an internal split--many members favored a purely federal system while others favored some form of federal/state partnership. President Roosevelt had broadly hinted his preference for a federal/state type system and this was in fact the recommendation the Committee ultimately put forward. Altmeyer supported this recommendation. Altmeyer never really clarified why he supported the mixed system, but he suggested that his main motive was that he was taking his cue from the the President. In any case, somewhere along the way he changed allegiances to become the principal advocate for federalization. He began this crusade in 1941 by criticizing the level of support provided by the States and pointing to the lack of uniformity in payment levels from State to State. He argued, in effect, that the present system was broken. It was nearly two years later, in March 1943, before he would openly argue that the broken system should be replaced by federal administration: " There is no question in my mind that combining the present State-by-State unemployment insurance system into a unified comprehensive contributory social insurance system would result in far simpler, more effective, and more economical administration. . . But of still greater importance than these administrative advantages is the fact that a truly national system of unemployment insurance would be much safer and sounder because of the wider spreading of the unemployment risk and the more effective utilization of reserves. . . A Federal unemployment compensation system could also provide much more adequate benefits for workers generally because of the wider spreading of the risks and the more effective utilization of reserves. It is most important that unemployment compensation benefits be made more adequate than they are at the present time. The weekly benefit rates in many States are insufficient to cover a reasonable proportion of the weekly wage loss that an unemployed worker suffers. Most serious of all is the fact that in most States the duration for which benefits are payable is so limited that a very high proportion of workers in receipt of unemployment compensation benefits exhaust their benefit rights before finding another job. For the country as a whole, even in a period of good employment, such as 1940 and 1941, 50 percent of the workers exhausted their benefit rights before they found another job. In some States the proportion ran as high as 65 and 75 percent. In a period of considerable unemployment these percentages would of course be still higher." His arguments had a certain logic, and viewed abstractly they probably had considerable merit. But logic can take you only so far, and powerful vested political interests were involved in the status quo and these interests were unlikely to yield to the gentle pleadings of the reasonable bureaucrat. Once the die had been cast in the report of the CES, and codified in the 1935 Act, there was no going back. The War Years as a Time of Opportunity for Social Insurance Although World War II was a vast tragedy for the nation and the world, Altmeyer saw it as presenting unique opportunities for the cause of social insurance. Several related economic shifts happened due to the War:

This unique set of circumstances led Altmeyer to argue that the War was in fact an opportunity for the nation . First, it raised the problem of coverage, since millions of people who had been covered were losing their coverage during their war service. Altmeyer seized on this anomaly and started arguing as early as October 1943, that coverage should be extended to service personnel in the form of "credits" toward Social Security coverage--an idea that would be adopted in 1956 as "gratuitous wage credits" for military service. He also made a very novel and somewhat creative argument for expanding coverage to non-covered groups based on an appeal for more effective financing of the war effort. His argument, articulated first in a November 1942 article, was that bringing new workers under the program now would result in an inflow of cash into the Treasury, which could be used to finance the war effort--without recourse to additional borrowing. And since there would be greater need for restored income security in the aftermath of the War, this form of financing would also help with post-War adjustments. President Roosevelt echoed Altmeyer's thesis by observing: "This is one case in which social and fiscal objectives, war and post-war aims are in full accord. Expanded social security, together with other fiscal measures, would set up a bulwark of economic security for the people now and after the war and at the same time would provide anti-inflationary sources for financing the war." In the unemployment insurance program his argument was that by federalizing the program now the adverse impacts of expected post-war surges in unemployment could be lessened --and that there was no time like the present, when revenues were high and claims were low. So the War, in Altmeyer's eyes, even facilitated his cherished goal of a federalized unemployment compensation system. (See April 1943 speech.) He also argued very forcefully (see March

1943 speech) that the provision of income security would be

especially pressing for children since many working fathers will

be killed or disabled by the War and their best hope of security

comes from participation in the programs of the Social Security

Act. This argues, according to Altmeyer, for an immediate expansion

of coverage to include all workers and to provide disability insurance

so that the nation's children can have the maximum of protection

in the post-war world. Long-Range Financing And Delays In Contribution Rate Increases The 1935 Act contained a rationalized schedule of tax rate increases designed by the actuaries to make the system self-supporting--in fact it was due to yield a $47 billion surplus by 1980. The fact that the system was designed to be in surplus was a source of political controversy. In the early years, one major conservative criticism of the program was over the issue of the surplus--conservatives being opposed on general political grounds to the accumulation of a tax-financed government surplus. The surplus was also a constant temptation to reduce the tax rates on the argument that the system did not really need the money. The issue about the surplus expressed itself in a conflict between advocates of "reserve financing" (the basis of the 1935 Act with its $47 billion surplus) and advocates of a "pay-as-you-go" approach, which would mean lower taxes in the early years and higher taxes in the distant future. The great temptation, of course, from a politician's point-of-view would be to opt for lower taxes and happier constituents now, with only the promise of higher taxes by and by. Altmeyer clearly saw this as one of the motives for supporting "pay-as-you-go" and he thought it was not responsible financing. Altmeyer offered his views in May 1937, only two months after assuming Chairmanship of the Board. Although he did not come right out and advocate reserve financing, he made it clear that the alternative "pay-as-you-go" approach had serious problems. "As a matter of fact, there is very little difference between the pay-as-you-go and the reserve systems in so far as the next few years are concerned. Violent disagreement arises, however, when the respective advocates undertake to project their imagination to the distant future, two generations hence. . . A second important reason for this violent disagreement is that the respective advocates fail to come to grips as to whether or not they would apply the pay-as-you-go system before or after there is practically universal coverage. . . The significance of the extent of coverage lies in the fact that unless the system operates on the reserve principle, either the future payroll taxes must ultimately increase to a figure double that now contemplated or there must be a substantial government subsidy, which means in effect that the uncovered portion of the population pays for a part of the cost of insuring the covered population. . . Moreover, if we start monthly benefit payments sooner, pay such benefits in more liberal amounts during the early years, add survivors' benefits and benefits for permanent total disability, we would be hard put to it to finance these benefits under even the existing tax rates. However, there is this real difference between pay-as-you-to advocates and the reserve advocates. The pay-as-you-go advocates would collect less money in payroll taxes in the early years of the system than the reserve advocates." Altmeyer then put his keen mind on the central political point regarding program financing. It is hard to imagine an observation with more currency than this one by Altmeyer in 1937: "It is absolutely vital to recognize clearly that if we adopt a pay-as-you-go system either before or after we have been able to achieve universal coverage, we must bear in mind the effect on our entire tax structure and government budget. To be concrete, if we adopt the pay-as-you-go system, we must make absolutely certain that at the same time we not only balance the budget but proceed to retire the government debt within the next generation through the imposition, let us hope, of progressive taxes, in order that we do not reach a period in the future when the burden of the interest charges on a large public debt and the burden of a large government subsidy to the Federal Old-Age Insurance plan cannot be sustained through current taxation." The production of a future surplus depended, of course, on the tax rates built into the system. Under the 1935 law, the rates were to start at 1% (on the employer and the employee), rising to 1.5% in 1940, 2% in 1943, 2.5% in 1946 and 3% in 1949. The 1939 Amendments eliminated the 1.5% rate and accelerated the payment of monthly benefits from 1942 to 1940, while adding major new benefits for survivors and dependents. In Altmeyer's view, these changes placed increased strain on the remaining rate schedule, making adherence to it more imperative. And yet in 1943 the Congress was considering delaying again one of the scheduled rate increases. In fact, this would become a pattern in Social Security financing. Scheduled increases were delayed or eliminated throughout the 1940s and 1950s. The 1% rate did not rise to 1.5% until 1950 and the 3% rate originally contemplated for 1949 did not actually start until 1960. Altmeyer sternly warned the Congress against this trend in testimony he gave in October 1943: "In the history of social insurance throughout the world the major difficulty of social insurance systems has been the lack of adequate financing of old-age retirement benefits. It is always easiest to delay levying the necessary insurance contributions, thus perpetuating and strengthening the belief that the insurance benefits are meager and the costs of the insurance system are low. Inevitably when the time comes to increase the taxes many reasons can always be advanced as to why the imposition of the additional taxes is unwise or impossible. In this country we are still in a position to avoid these mistakes by getting clearly established now that if our people want social insurance they must be willing to pay for it. The time to obtain the necessary contributions is when people are able to pay for the insurance and are willing to pay for it because they can be shown that they are getting their money's worth. If we should let a situation develop whereby it eventually becomes necessary to charge future beneficiaries rates in excess of the actuarial cost of the protection afforded them, we would be guilty of gross inequity and gross financial mismanagement, bound to imperil our social insurance system."

|

||||

| Chapter 6: A Bureaucrat with a Broad Portfolio | |||

|

Other Duties As Assigned One of Altmeyer's most important "extra-curricular" activities was his key role in supporting the development of social insurance in the Americas. As early as 1939 he was serving as Chairman of the U.S. delegation to the Conference of American States of the International Labor Organization. He headed the American Delegation to the first Inter-American Conference on Social Security, in Santiago, Chile. From 1942-1952 he was Chairman of the Permanent Inter-American Committee on Social Security. In this role he was instrumental in bringing Social Security to many central and South American nations. He is fondly remembered to this day throughout Latin America.

A Couple of Stray Brass Rings At least twice in his career Altmeyer was considered for "higher" office and was passed by. It is not clear why he was passed over, and it is far from certain that he cared. After serving as the Chairman of the independent Social Security Board for more than two years, Altmeyer was clearly disappointed and chagrined when, in July 1939, President Roosevelt stripped the SSB of its independent status and directed that the Board would henceforth report to the new Federal Security Agency and its Director, Paul V. McNutt. Although their relations were cordial, Altmeyer certainly disliked this change in his and the Board's status. McNutt was primarily a politician (McNutt was planning to run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1940 if FDR didn't seek a third term). Altmeyer, in addition to being an able administrator, was an intellectual. He was as much at home in social insurance and economic theory as in the nuts and bolts of running Social Security. Whether he viewed McNutt as a peer is hard to say, and there were some incidents of serious conflict between the two of them.

An Incident in Defense of Social Security The leading alternative to Social Security in the early years were so-called "flat benefit" schemes (the Townsend Plan was one such scheme). Under these types of plans, a flat amount would be paid to all recipients, without regard to past earnings levels or contributions to any social insurance system. Conservatives favored these types of plans as an alternative to Social Security. And apparently McNutt did as well. In 1940 McNutt decided to make public his preference for a flat-rate universal pension to replace the Social Security program. Altmeyer knew that President Roosevelt was adamantly opposed to flat-rate pensions, as was he. When Altmeyer saw a draft of McNutt's speech he rushed to Washington and showed it to Roosevelt. The President gave Altmeyer instructions to stop McNutt from delivering the speech. Since McNutt was already on the train to New York, Altmeyer had to dispatch Ellen Woodward (a member of the Board) by plane. She finally caught up with McNutt as he was standing at the podium on the stage, clearing his throat to start his speech. Woodward motioned McNutt to the wings and delivered the President's edict. She handed him a new speech that Altmeyer had prepared. A red-faced McNutt returned to the podium and made Altmeyer's speech rather than his own, without any mention of his views on Social Security and flat-rate pensions. When McNutt left FSA in 1945 Altmeyer was rumored to be the heir apparent. Instead, the job went to McNutt's deputy, Watson Miller. Altmeyer stayed put as head of the Social Security Board. He never expressed any disappointment in remaining as the head of the SSB. Also in 1945 Altmeyer was considered for another high office. The Veterans Administration job was coming vacant and Altmeyer was the favored candidate of the remaining FDR "brain trusters." But there were bigger fish trolling in that sea, and General Omar Bradley, fresh from the Allied victories in the War, was tapped by President Truman to head the VA. Altmeyer was re-appointed by President Truman, in July 1945, to another six-year term as Chairman of the SSB. Once again, Altmeyer seemed destined for bigger things, but Social Security held him. It does not seem that either of these near-misses caused Altmeyer any sleepless nights as his heart was always with the Social Security program. He was, after all, called by FDR and others "Mr. Social Security" and he had a parental attachment to the program and the agency that administered it.

|

|||

| Chapter 7: Death By Preposition | |||||

|

Death By Preposition Altmeyer was appointed to his job by President Roosevelt in early 1936. He was confirmed by the Senate as a political appointee. He held the top position at Social Security for nearly 20 years, through the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. During this time he acquired a special status in the minds of many. He was not universally viewed as a political appointee, but was rather seen by most people as a career civil servant. Technically, however, he was a political appointee and he fully expected to leave once the new administration was fully in place, following the 1952 elections. In fact, he had already announced, prior to the election, that he would retire on May 8, 1953, when he reached the minimum age for full retirement. But as soon as the new Secretary, Oveta Culp-Hobby, took office she made it clear that Altmeyer was persona non grata in her eyes. She excluded him from meetings, ignored his memos, and made a point of being cool to him whenever they did have any interaction. Altmeyer described Hobby this way: "She gave the impression of glacial calmness, impersonality, objectivity, and decisiveness." But, Hobby, according to Altmeyer's account of those who knew her well, ". . . was in reality a sensitive, shy, and uncertain person who found it painful to deal with fellow officers and to make difficult decisions." So perhaps it suited her that a scheme was found in which she did not have to fire Altmeyer directly. Instead, a Reorganization Plan was submitted to Congress by the Administration under which the job that Altmeyer held, the Commissioner for Social Security, would be abolished and a new job created, the Commissioner of Social Security. By this simple maneuver Altmeyer would be out of a job and there would be a vacancy for a new Republican political appointee. And over this preposition the storied career of Arthur J. Altmeyer was ended. But there was a problem. The Reorganization Plan went to Congress on March 12, with an effective date of May 11th (three days after Altmeyer attained retirement age). As the Plan emerged from Congress, the effective date had been changed to April 11th. It is unclear whether Hobby played a hand in this change, but she clearly did nothing to prevent it. This created a problem for Altmeyer since it meant that by being forced to retire 27 days too soon, his wife would lose potential survivors benefits. When this fact became known, it was a brief embarrassment to the Administration who was seen to be treating Altmeyer callously. Especially since the Administration had not named a replacement for him, and the law allowed former officials to stay in their old jobs for up to 60 days, if the President asked them to do so. As the political fall-out grew, Secretary Hobby contacted Altmeyer, literally as he was in the process of cleaning out his desk, with an offer to hire him as a "consultant" for 30 days so he could earn his full retirement. A proud man, with a strong sense of propriety, Altmeyer refused the offer. He later said, "I didn't feel justified in taking money for any such make-work proposition or boondoggle. So, I declined."

|

|||||

| Chapter 8: Life After Government | |||

|

|

|||

| Chapter

10: Tributes to a Life of Accomplishment |

|||

|

There are a handful of people whose names stand out in the history of Social Security in America. Arthur Altmeyer is certainly on this short list. And when it comes to the history of the Social Security Administration, Altmeyer stands alone as by far the most important figure. It was Altmeyer who gave SSA its basic character and operating philosophy. It was Altmeyer who, more than any other person, shaped the ethos of public service that has characterized SSA over the years. Altmeyer described that ethos in this way: "I think most of the success was due to the employee training program and the insistence that we were a social agency. We kept clerks here, as well as higher -ups, for months before they went out and set up local offices. So they had religion. They had it complete. . . I'm sure we would have been licked even if we had done everything as well as could be expected administratively without that. It was the character that was established." If SSA had religion, Altmeyer wrote the canon. SSA's headquarters in Baltimore bears his name. It is a fitting tribute. "Arthur could discuss basic concepts of the right to

insurance and to assistance and services with social workers.

He could discuss the constitutional implications with lawyers--many

times reversing their opinions and judgments. At the same time,

he could explore with Bob Myers the intricacies of mathematical

cost calculations of social insurance. In an era of increasing

specialization he demonstrated the importance, at the highest

levels of government, of a variety of competences . . . so vitally

necessary to make . . . programs (such) as those included in the

Social Security Act of 1935 become living, working realities." "This enormously able man was a guide and inspiration

to all of us who knew him well, and his shaping of the social

security program and its administration entitle him to high rank

among the outstanding public servants of all time." "Those who worked closely with him knew that besides

his superior intellectual and administrative abilities Arthur

Altmeyer was a man of sensitivity, compassion and integrity."

|

|||

| Chapter 9: Death & Burial | |

|

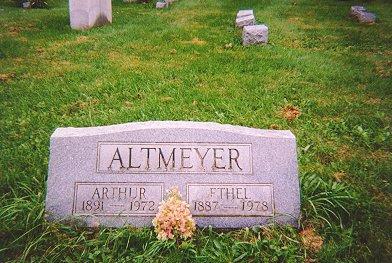

Altmeyer's last days were marked by several bouts of illness which required extended hospital stays. Through it all he maintained his intellectual interest in ongoing developments in Social Security. Arthur finally died on Monday, October 16, 1972. Funeral services were held at the First Unitarian Society in Madison, presided over by the Rev. Max Gaebler. Altmeyer was laid to rest in Madison's Forest Hills Cemetry on Thursday October 19, 1972. A memorial service was held a few weeks later in Washington, D.C. Ethel would survive him for another six years, and was buried alongside her husband in their modest plot in Madison in 1978.

|

| Chapter 11: Key Dates in the Life & Career of Arthur J. Altmeyer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||